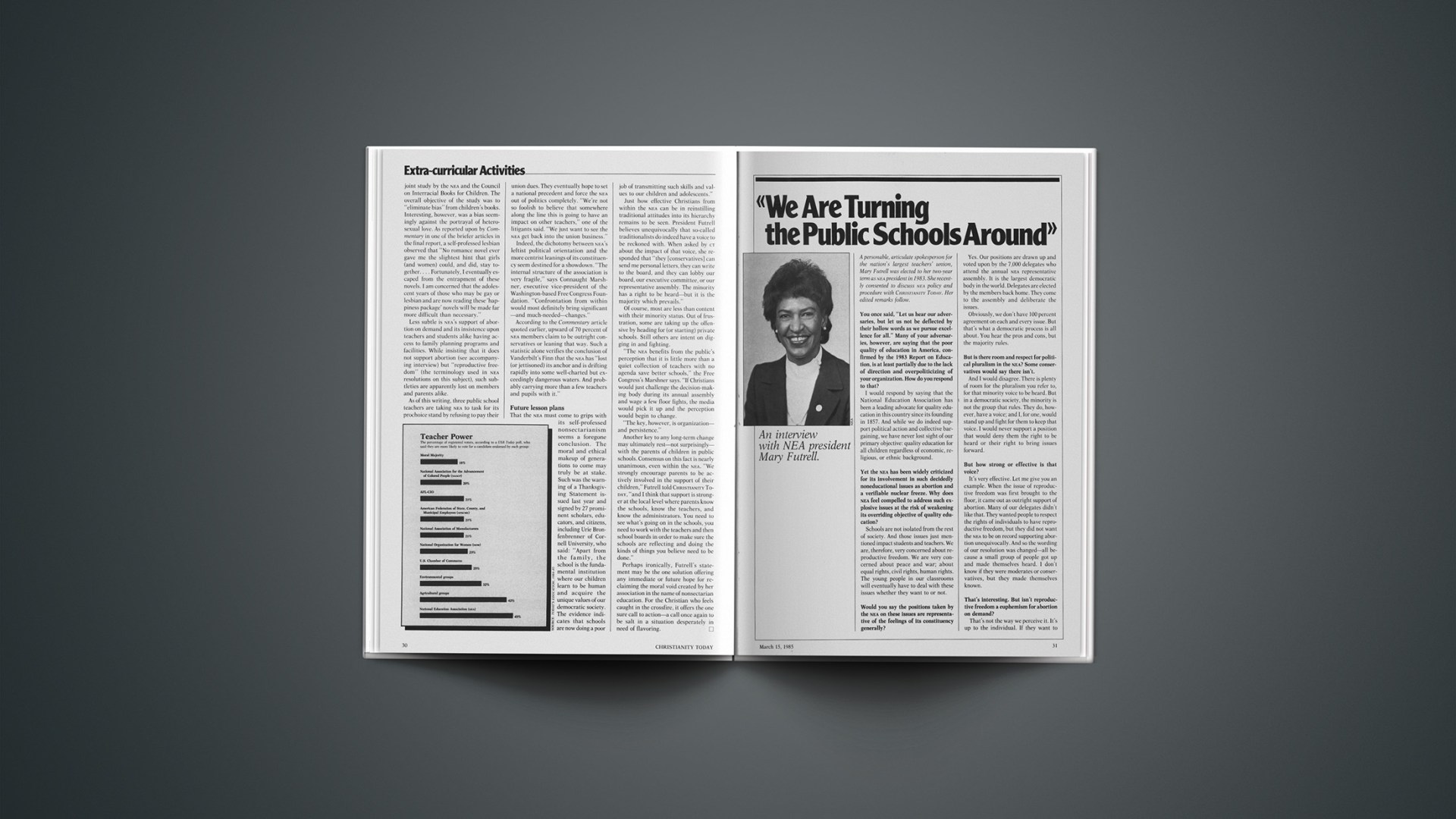

An interview with NEA president Mary Futrell.

A personable, articulate spokesperson for the nation’s largest teachers’ union, Mary Futrell was elected to her two-year term as NEA president in 1983. She recently consented to discuss NEA policy and procedure with CHRISTIANITY TODAY. Her edited remarks follow.

You once said, “Let us hear our adversaries, but let us not be deflected by their hollow words as we pursue excellence for all.” Many of your adversaries, however, are saying that the poor quality of education in America, confirmed by the 1983 Report on Education, is at least partially due to the lack of direction and overpoliticizing of your organization. How do you respond to that?

I would respond by saying that the National Education Association has been a leading advocate for quality education in this country since its founding in 1857. And while we do indeed support political action and collective bargaining, we have never lost sight of our primary objective: quality education for all children regardless of economic, religious, or ethnic background.

Yet the NEA has been widely criticized for its involvement in such decidedly noneducational issues as abortion and a verifiable nuclear freeze. Why does NEA feel compelled to address such explosive issues at the risk of weakening its overriding objective of quality education?

Schools are not isolated from the rest of society. And those issues just mentioned impact students and teachers. We are, therefore, very concerned about reproductive freedom. We are very concerned about peace and war; about equal rights, civil rights, human rights. The young people in our classrooms will eventually have to deal with these issues whether they want to or not.

Would you say the positions taken by the NEA on these issues are representative of the feelings of its constituency generally?

Yes. Our positions are drawn up and voted upon by the 7,000 delegates who attend the annual NEA representative assembly. It is the largest democratic body in the world. Delegates are elected by the members back home. They come to the assembly and deliberate the issues.

Obviously, we don’t have 100 percent agreement on each and every issue. But that’s what a democratic process is all about. You hear the pros and cons, but the majority rules.

But is there room and respect for political pluralism in the NEA? Some conservatives would say there isn’t.

And I would disagree. There is plenty of room for the pluralism you refer to, for that minority voice to be heard. But in a democratic society, the minority is not the group that rules. They do, however, have a voice; and I, for one, would stand up and fight for them to keep that voice. I would never support a position that would deny them the right to be heard or their right to bring issues forward.

But how strong or effective is that voice?

It’s very effective. Let me give you an example. When the issue of reproductive freedom was first brought to the floor, it came out as outright support of abortion. Many of our delegates didn’t like that. They wanted people to respect the rights of individuals to have reproductive freedom, but they did not want the NEA to be on record supporting abortion unequivocally. And so the wording of our resolution was changed—all because a small group of people got up and made themselves heard. I don’t know if they were moderates or conservatives, but they made themselves known.

That’s interesting. But isn’t reproductive freedom a euphemism for abortion on demand?

That’s not the way we perceive it. It’s up to the individual. If they want to have an abortion, that is their right. If they don’t want one, that is also their right. We’re not saying we support abortion. People interpret it that way, but that is not our interpretation.

What effect has your unabashed identification with the Democratic party had on the NEA?

We believe very strongly that education is a bipartisan issue and have worked very hard to make sure that the NEA is a bipartisan organization. I must confess, though, it has been difficult keeping the Republican avenue open. Many of our members report having a great deal of difficulty getting involved in their local or state Republican party and being accepted as active members.

Are there programs like tuition tax credits where the NEA would be willing to compromise its opposition in order to gain the ear of the current administration?

I must honestly say that we would not be willing to compromise our opposition to tuition tax credits. We believe, number one, that the public schools are already underfunded, especially at the federal level, where this administration has cut funding by 25 percent. We are told there is a rising tide of mediocrity in the classroom and yet are also told not to expect any more assistance from the federal government. It is ironic that at a time when we are told there are no new dollars to be had, the administration is trying to set up a program advocating tuition tax credits or vouchers for private and/or parochial schools.

But as I have listened to this administration, I have heard many areas where we, in fact, agree. They talk about improving discipline in the schools, more emphasis on the basics, more homework, better training for teachers. They talk about getting rid of drug abuse in the schools. So do we. Therefore, I think we can work with the administration in these areas.

How would you assess your relationship with the religious community?

The relationship between the NEA and the religious community is not as hostile as many people would like to think it is. We work together in many instances, and we will continue to work together whenever we can.

I would venture to say that the overwhelming majority of our members are not only religious, but practice their religion. They are in the choir, on the board of trustees, teach Sunday school, and so on. I am a practicing Baptist and have been all my life. But I work with the Jewish community. I work with the fundamental Baptist community. I work with the Methodists. In short, I work with whomever is willing to work with me.

There are, of course, areas of disagreement—school prayer for one. But let me say that the NEA is not opposed to individual prayer in school. What we oppose is group-led prayer in the school, which is unconstitutional. Can Johnny say a prayer before a test? Absolutely. Can Jane say grace before eating lunch? Absolutely. Do we ever try to stop the basketball team or the football team from saying a prayer before a game? No, we don’t.

But you have to realize that when we look at the makeup of our individual classrooms, we see different nationalities and different religions. There is, therefore, no one religion that should be imposed on such a captive audience.

And yet you stood up against nearly all religious groups in your opposition to equal access legislation.

Our concern with the original bill was that it would open up schools not only to religious groups but to all groups. Once you say equal access, you have to make provisions for all groups. Our children, then, would have been exposed to all kinds of groups, extremists at both ends of the spectrum.

But I do believe that we worked with the legislators and were able to modify, with the formation of guidelines, the final bill to our satisfaction.

Is there any way the NEA can build a better bridge between itself and the religious community?

As I said, we do work very closely with the religious community on a variety of issues, especially those dealing with civil rights. We don’t ask people to endorse our entire agenda. Where we can work together, we need to work together. Where we disagree, we disagree. But we will do so in such a way that we don’t simply split and never work together again.

Why do you think private education is on the upswing?

According to all the information I have seen, private and/or parochial schools have not achieved any more support than they have had all along, which is about 10, maybe 11, percent of the student population. As a matter of fact, back in the late sixties, I believe it was up to about 13 to 15 percent.

There will always be parents who send their children to private schools regardless of the condition of public schools. But I think those parents who do this on the assumption that all public schools are bad are often basing their decision on what they have seen, read, or heard second- or thirdhand. That is not to say the schools are perfect; but I believe we are turning the public schools around. I think they are better than they have been in a long time, and I think they will be better than they have ever been because of the efforts of a large group of people.

Does competition from private schools force public schools to improve their quality of education?

No. I think a lot Americans fail to realize that when the educational system started in this country it started as a private school system. And to a large degree, that school system was a religious one. Yet the general public moved away from private to public education to insure that each and every child in this country could, in fact, get an education. The public schools have to open their doors to everyone. We cannot turn away any child. If there is competition, it’s between public schools in the same school system.

Many people send their children to private schools because they feel that those in the public schools are prejudiced against their particular religious viewpoint. Do you see the public schools as being secular to the point where teachers are prejudiced against Christian viewpoints?

That’s a tough question. My personal answer would be no. And one of the resolutions we have is to teach children to respect all kinds of religions, cultures, and points of view. But I also have to admit that the public schools are not sectarian, and that was the way they were established. Moreover, I look at the Constitution, which says we shall not have group-led prayer. So, based upon the way that the schools have always been structured, and based on the way that the Supreme Court has dealt with the public schools, we are not advocates of sectarian religion in the schools.