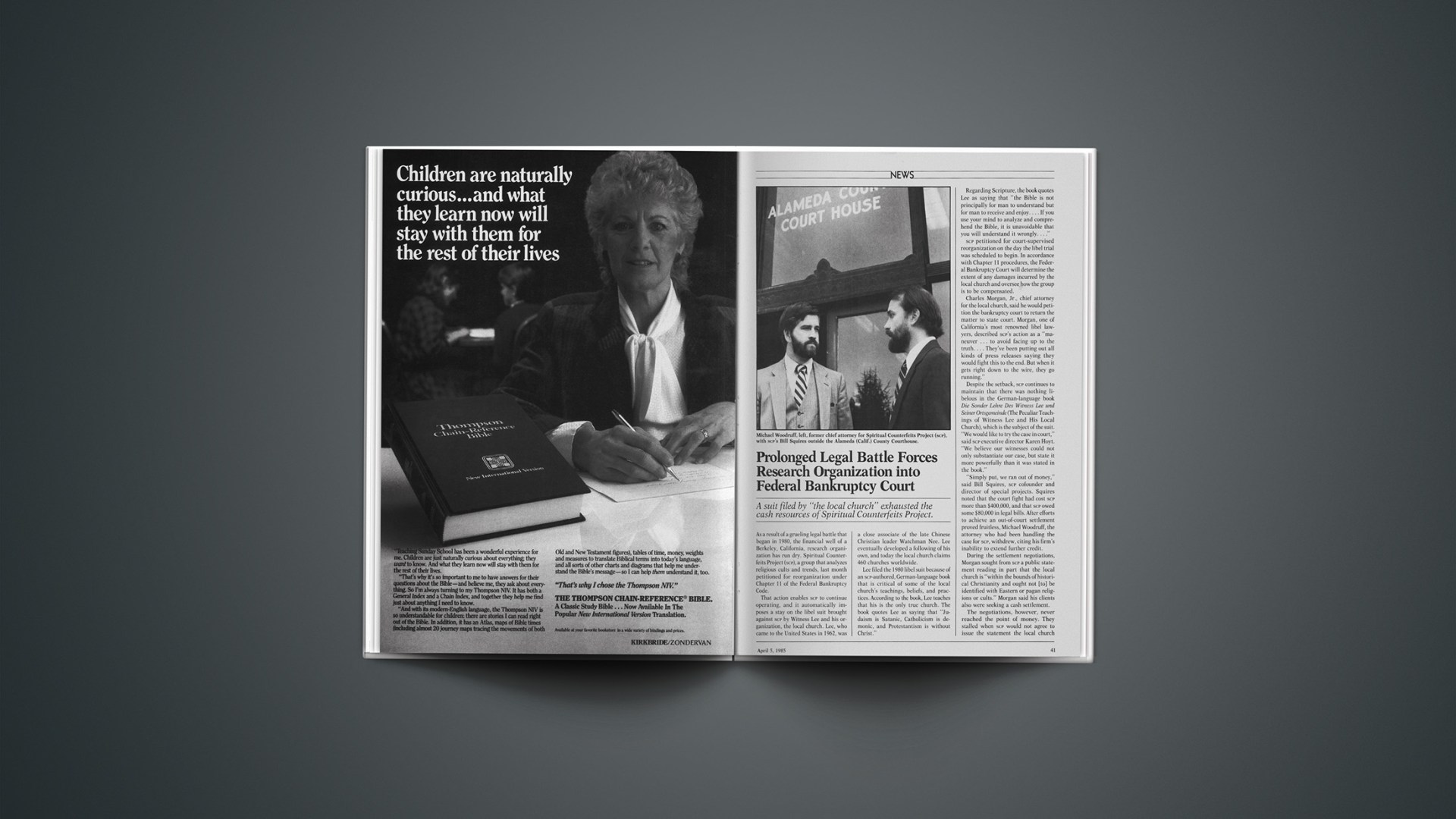

A suit filed by “the local church” exhausted the cash resources of Spiritual Counterfeits Project.

As a result of a grueling legal battle that began in 1980, the financial well of a Berkeley, California, research organization has run dry. Spiritual Counterfeits Project (SCP), a group that analyzes religious cults and trends, last month petitioned for reorganization under Chapter 11 of the Federal Bankruptcy Code.

That action enables SCP to continue operating, and it automatically imposes a stay on the libel suit brought against SCP by Witness Lee and his organization, the local church. Lee, who came to the United States in 1962, was a close associate of the late Chinese Christian leader Watchman Nee. Lee eventually developed a following of his own, and today the local church claims 460 churches worldwide.

Lee filed the 1980 libel suit because of an SCP-authored, German-language book that is critical of some of the local church’s teachings, beliefs, and practices. According to the book, Lee teaches that his is the only true church. The book quotes Lee as saying that “Judaism is Satanic, Catholicism is demonic, and Protestantism is without Christ.”

Regarding Scripture, the book quotes Lee as saying that “the Bible is not principally for man to understand but for man to receive and enjoy.… If you use your mind to analyze and comprehend the Bible, it is unavoidable that you will understand it wrongly.…”

SCP petitioned for court-supervised reorganization on the day the libel trial was scheduled to begin. In accordance with Chapter 11 procedures, the Federal Bankruptcy Court will determine the extent of any damages incurred by the local church and oversee how the group is to be compensated.

Charles Morgan, Jr., chief attorney for the local church, said he would petition the bankruptcy court to return the matter to state court. Morgan, one of California’s most renowned libel lawyers, described SCP’s action as a “maneuver … to avoid facing up to the truth.… They’ve been putting out all kinds of press releases saying they would fight this to the end. But when it gets right down to the wire, they go running.”

Despite the setback, SCP continues to maintain that there was nothing libelous in the German-language book Die Sonder Lehre Des Witness Lee und Seiner Ortsgemeinde (The Peculiar Teachings of Witness Lee and His Local Church), which is the subject of the suit. “We would like to try the case in court,” said SCP executive director Karen Hoyt. “We believe our witnesses could not only substantiate our case, but state it more powerfully than it was stated in the book.”

“Simply put, we ran out of money,” said Bill Squires, SCP cofounder and director of special projects. Squires noted that the court fight had cost SCP more than $400,000, and that SCP owed some $80,000 in legal bills. After efforts to achieve an out-of-court settlement proved fruitless, Michael Woodruff, the attorney who had been handling the case for SCP, withdrew, citing his firm’s inability to extend further credit.

During the settlement negotiations, Morgan sought from SCP a public statement reading in part that the local church is “within the bounds of historical Christianity and ought not [to] be identified with Eastern or pagan religions or cults.” Morgan said his clients also were seeking a cash settlement.

The negotiations, however, never reached the point of money. They stalled when SCP would not agree to issue the statement the local church wanted. Said SCP spokesman Kirk Bottomly: “Their terms required us to say things about the local church that could be interpreted by the public as an endorsement of the group. They wanted specific retractions that we couldn’t in good conscience make.”

Morgan said the local church would continue its legal battle against the book’s primary author, Neil Duddy, a codefendant in the suit. No longer working with SCP, Duddy is a doctoral candidate at the University of Aarhus in Denmark. In a telephone interview, Duddy said he didn’t have the financial means to provide for his defense and would concede the case by not appearing in court. Duddy maintains, however, that “the book is a very thorough study,” and that it is “accurate and defensible.”

InterVarsity Press (IVP) published an English version of Duddy’s book in 1981. Morgan said the possibility of legal action against IVP “has not been ruled out.”

Morgan defended the local church’s desire to be reasonable in all negotiations with critics. “You can’t imagine how much my clients want to do it the Christian way,” he said. “[They] don’t want to destroy anybody.… All they want is for the truth to come out.”

But SCP views itself as a victim of financial pressure on the part of the local church. Squires was quoted in a February press release as saying that “the plaintiffs’ endless depositions, interrogatories and discovery motions have driven our costs through the ceiling.”

Hoyt said if the local church ultimately wins the court battle, publishers will be hesitant to express any view they can’t afford to defend in court. “If you’re a criminal, you’re appointed a defense lawyer,” she said. “But if you’re just a citizen, you can have all your assets taken away and have a judgment issued against you without ever having the chance to say in court what you believe is the truth.”

Hoyt said SCP has felt “left alone by the Christian community, which says, ‘Be of good cheer, and we’ll pray for you.’ “

SCP is not the only organization that has been sued by the local church. In 1983, Witness Lee’s group settled out of court with Thomas Nelson Publishers. Details were confidential, but Nelson ceased distribution of the book The Mind Benders, which contained a chapter critical of the local church.

Attorneys for the local church have carried on lengthy correspondence with Tyndale House Publishers over a chapter in Larson’s Book of Cults. Tyndale House president Mark Taylor said the end of the discussions “is not in sight.”

Robert Bowman, of the Christian Research Institute (CRI), expressed concern that CRI could be the next organization to be sued. Bowman said SCP’s conclusions on the local church are similar to those of cri founder and director Walter Martin, as expressed in the book The New Cults (Vision House).

Advice Columnist Helps Combat Rumor About Sacrilegious Movie

Syndicated advice columnist Ann Landers has succeeded where national religious groups, legal authorities, and investigative reporters had failed. She deflated a baseless rumor that a film portraying Jesus as a homosexual was being made.

The rumor has prompted hundreds of thousands of protest letters and telephone calls to state and federal officials during the past several years. Earlier this year, Illinois Attorney General Neil F. Hartigan enlisted Landers’s help in combating the rumor. She published a letter from Hartigan, in which he said that his office and the Associated Press “can’t find a shred of truth … that such a film was ever in production.”

The story first surfaced in 1977 in Modern People News, a now-defunct suburban Chicago magazine. The magazine asked for reader reaction, and the resulting protest campaign is still going strong. Last year Hartigan’s office received 110,000 letters from 41 states and more than a dozen countries, including India, Brazil, Cambodia, and Australia, said William Schaub, Hartigan’s administrative assistant.

Letters have been sent to the U.S. Department of Justice and to state officials outside Illinois. However, Illinois officials have received the lion’s share, in part because it was thought that Modern People News was making the movie. The letter writers wanted Hartigan to put a stop to the film.

“We’ve worked with many religious groups to [try to] stop the rumor, including the National Council of Churches; sent out press releases; sent replies to those writing us,” Schaub said. “And we’ve just asked TV evangelists to help. But the most successful, so far, has been [the] Ann Landers [column].” Instead of 1,000 letters and 60 phone calls per week, Hartigan’s office now receives 50 letters and 10 calls weekly.

Schaub said no single group or individual is behind the protest, making it difficult to stamp out. “If there’s a culprit,” he said, “it’s the abundance of … [photocopying] equipment. People get the chain letter, easily run off a few copies, and send them to friends, or take them to work, school, or business.”