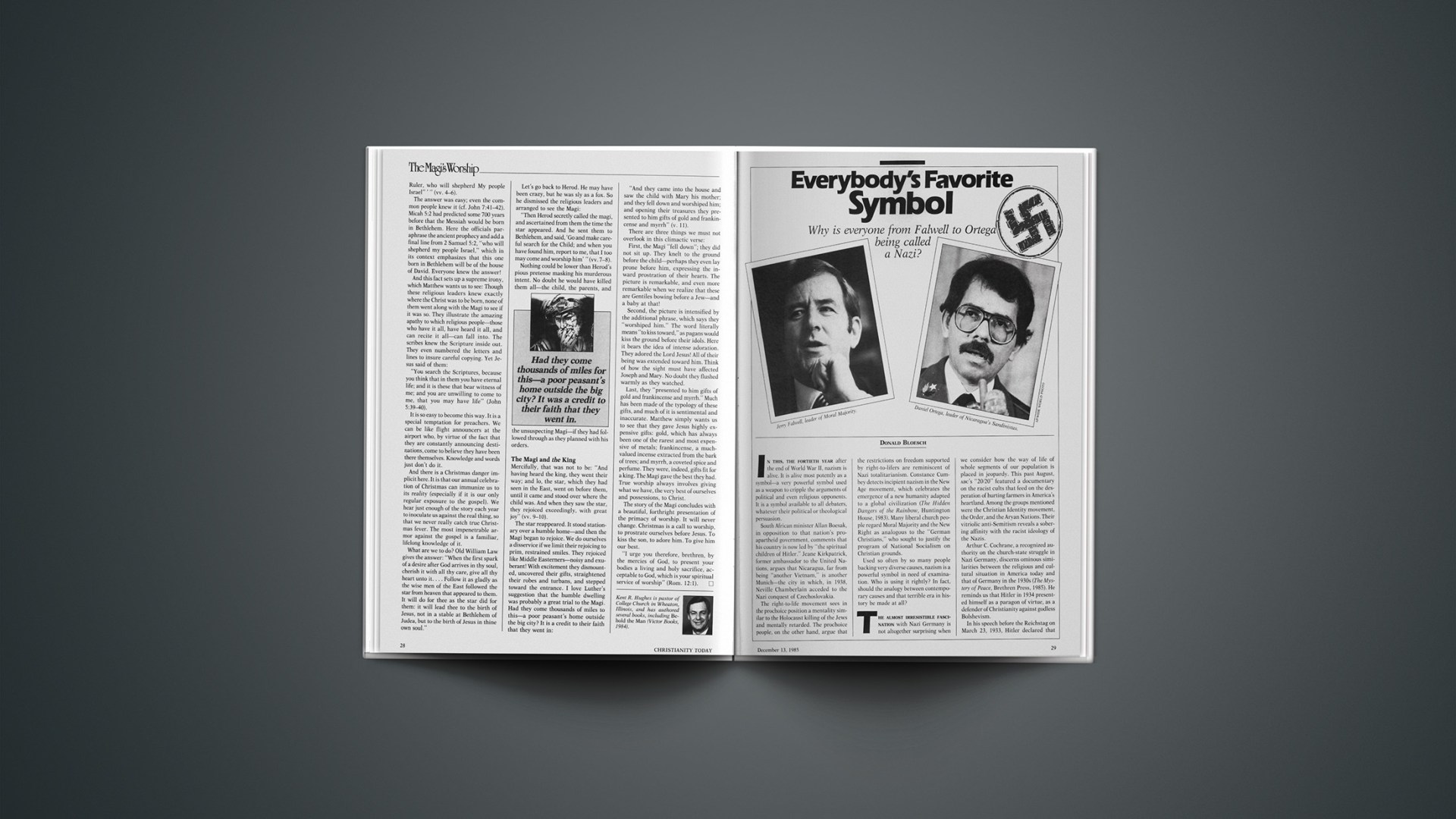

Why is everyone from Falwell to Ortega being called a Nazi?

In this, the fortieth year after the end of World War II, nazism is alive. It is alive most potently as a symbol—a very powerful symbol used as a weapon to cripple the arguments of political and even religious opponents. It is a symbol available to all debaters, whatever their political or theological persuasion.

South African minister Allan Boesak, in opposition to that nation’s pro-apartheid government, comments that his country is now led by “the spiritual children of Hitler.” Jeane Kirkpatrick, former ambassador to the United Nations, argues that Nicaragua, far from being “another Vietnam,” is another Munich—the city in which, in 1938, Neville Chamberlain acceded to the Nazi conquest of Czechoslovakia.

The right-to-life movement sees in the prochoice position a mentality similar to the Holocaust killing of the Jews and mentally retarded. The prochoice people, on the other hand, argue that the restrictions on freedom supported by right-to-lifers are reminiscent of Nazi totalitarianism. Constance Cumbey detects incipient nazism in the New Age movement, which celebrates the emergence of a new humanity adapted to a global civilization (The Hidden Dangers of the Rainbow, Huntington House, 1983). Many liberal church people regard Moral Majority and the New Right as analogous to the “German Christians,” who sought to justify the program of National Socialism on Christian grounds.

Used so often by so many people backing very diverse causes, nazism is a powerful symbol in need of examination. Who is using it rightly? In fact, should the analogy between contemporary causes and that terrible era in history be made at all?

The almost irresistible fascination with Nazi Germany is not altogether surprising when we consider how the way of life of whole segments of our population is placed in jeopardy. This past August, ABC’s “20/20” featured a documentary on the racist cults that feed on the desperation of hurting farmers in America’s heartland. Among the groups mentioned were the Christian Identity movement, the Order, and the Aryan Nations. Their vitriolic anti-Semitism reveals a sobering affinity with the racist ideology of the Nazis.

Arthur C. Cochrane, a recognized authority on the church-state struggle in Nazi Germany, discerns ominous similarities between the religious and cultural situation in America today and that of Germany in the 1930s (The Mystery of Peace, Brethren Press, 1985). He reminds us that Hitler in 1934 presented himself as a paragon of virtue, as a defender of Christianity against godless Bolshevism.

In his speech before the Reichstag on March 23, 1933, Hitler declared that the national government regarded the two Confessions (Protestantism and Roman Catholicism) as “the most important factors for the preservation of our nationality.” He went on to say: “The national Government will provide and guarantee to the Christian Confessions the influence due them in the schools and education. It is concerned for genuine harmony between Church and State. The struggle against materialism and for the establishment of a true community in the nation serves just as much the interests of the German nation as it does those of our Christian faith.”

Those Christians who sought to work with the National Socialists included people from a wide theological spectrum, liberal as well as conservative. These “German Christians,” who were intent on accommodating Christian faith to National Socialist ideology, endorsed the so-called Aryan paragraph that forbade persons of Jewish descent from holding office in the churches. The noted Lutheran scholar Paul Althaus welcomed the National Socialist revolution as “a miracle of God.” As late as 1939, leading bishops in the Lutheran church issued a statement in support of the Reich minister for church affairs: “In the realm of faith there is a sharp opposition between the message of Jesus Christ and his apostles and the Jewish religion.… In the realm of our national life a serious and responsible racial politics is necessary for the preservation of the purity of our people” (cited by Cochrane, The Mystery of Peace).

The more radical German Christians, whose position was practically indistinguishable from that of the racist and nationalist cults, made an attempt to resymbolize the faith and thereby bring it more into harmony with the aspirations and goals of National Socialism. God was envisioned as the soul of the German race or as the creative force within history. Jesus Christ was seen as cosmopolitan, the generic man, rather than Jewish. Some tried to show that he was actually a member of the Aryan race. The Old Testament was dismissed as incurably Jewish, and only parts of the New Testament were accepted as authoritative.

The teachings of Jesus, which were recognized as having universal significance, were elevated over the message of Paul, which was criticized for being exclusivistic and particularistic. New liturgies were drawn up that sought to introduce “inclusive language,” which in effect de-Judaized the faith. An appeal was made to new revelations in nature and history that would supplement or even supersede the revelation in the Bible.

Where The Parallels Fall Down

The parallels between the cultural and religious situation in Germany in the later 1920s and 1930s and the period in which we are living today are indeed striking. We, too, as a nation are involved in a struggle with international communism, though this is mainly external rather than internal. (The Communist party in Germany, before Hitler gained power, posed a grave threat to the stability of that country.) Our leaders are also talking peace while building up a strong military defense. They, too, are emphasizing the need for religious and moral values in our public school system, though the civil religion they espouse is qualitatively different from either Catholic or evangelical Christianity.

At the same time, the parallels collapse at certain key points. First, our cultural heritage is democratic egalitarianism, whereas democracy had no deep roots in the German tradition. Obedience to authority, respect for hierarchy and militarism were characteristic of the German nation from its inception. In addition, the Nazis were able to draw on the long and sometimes illustrious philosophical tradition in Germany, including such luminaries as Meister Eckhart, Fichte, Hegel, Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Eduard von Hartmann, and Paul de Lagarde. (They frequently misread or willfully misrepresented some of these scholars.)

The philosophers who have shaped the American ethos are of a quite different stripe: Jefferson, Emerson, Thoreau, Walt Whitman, William James, Charles Pierce, and John Dewey. The American philosophical tradition is empirical, pragmatic, and utilitarian, characterized for the most part by an emphasis on self-reliance and individualism.

America, to be sure, has had its problems with racism, from before the Civil War and to the present. A plethora of racist organizations is increasingly gaining a hearing: the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan; the Church of the Aryan Nations; the Order; the Christian Identity movement; the Lord’s Covenant Church; and the American Nazi party.

Yet all of these movements stand at odds with the American democratic tradition as well as with Judeo-Christian values. Even though racism exists as a present threat in our society, it is doubtful that a racist ideology could emerge as a live option in the political and cultural arena. The American educational system, the mass media, the religious authorities (both conservative and liberal), and the political establishment are at one in condemning racism in all its malignant forms. The recent upsurge of popular sentiment against South Africa attests to the validity of this assumption.

The New Religious Right (Falwell, Robertson, LaHaye) is often compared to the German Christians. There is some truth in this, but the parallels break down in certain critical areas. First, the Religious Right is much more interested in a reaffirmation rather than a resymbolization of the Christian faith (though some sporadic resymbolizing occurs in the positive thinking movement). Again, far from being anti-Semitic, the Religious Right is at the forefront in the support for Israel. (To be sure, anti-Semitism is very much present in the cultic movements that constitute the so-called Radical Right, but their influence is thus far marginal.)

Finally, the Religious Right is adamantly committed to right to life, whereas the Nazis advocated doing away with the mentally retarded, the deformed, and the hopelessly senile. They opposed abortions for Germans but not for minority races.

Where Parallels Exist

The German Christian movement signified an egregious accommodation of Christian faith to a secular ideology, in this case National Socialism. Similarly today we see well-meaning Christians trying to bring the faith into a working relationship with ideologies endemic to American culture, ideologies of a democratic or egalitarian hue. It is in ideological alignments that the real parallels between American religion and the Nazi period can be discerned.

The New Religious Right is not racist or collectivist, but it can be accused of trying to unite the basic precepts of faith with conservative ideology, which celebrates free-enterprise capitalism and the unfettered market. Conservative economic theory is given biblical sanction by the evangelical Right, including leaders like Jerry Falwell, D. James Kennedy, and Gary North. Falwell has these reassuring words for the comfortable: “Ownership of property is biblical. Competition in business is biblical. Ambitious and successful business management is clearly outlined as a part of God’s plan for His people” (Listen, America!, Doubleday, 1981).

Sad to say, financial success is widely regarded in evangelical and fundamentalist circles as a cardinal evidence of Christian faith. This so-called prosperity doctrine reflects an ideological distortion of the faith and undermines the credibility of evangelicalism among thoughtful and sensitive people, both Christian and non-Christian.

But the Left, too, is not without its ideological trappings. Christian feminists are guilty of buying into secular feminist ideology and thereby reinterpreting the faith in light of a secular agenda. Like the German Christians, many Christian feminists are bent on resymbolizing the faith. God is no longer the Almighty Creator, Father, and Lord, but now becomes the “Womb of Being,” “the Empowering Matrix,” and “Immanent Mother.”

Feminists appeal not to the Bible as such but to the cultural experience of what it means to be a woman in a man’s world. Elisabeth Schüssler-Fiorenza holds that “only the nonsexist and non-androcentric traditions of the Bible and the nonoppressive traditions of biblical interpretation have the theological authority of revelation if the Bible is not to continue as a tool for the oppression of women” (Charles Curran, ed. Readings in Moral Theology, Vol. 4).

The ideological thrust in process theology is apparent in its bold attempt to reinterpret the doctrine of God in order to bring it into accord with the democratic experience. Instead of an almighty Creator, God now becomes a “fellow-sufferer who understands” (Whitehead) or a creative process in the universe. Progress in the spiritual as well as social life is contingent on “creative interchange” in which God realizes his purposes in cooperation with his creatures. We contribute to God’s self-fulfillment just as he contributes to ours. Here we see how religion begins to reflect the philosophical and mythological vision of a particular culture, as was the case with the German Christians in Nazi Germany.

Liberation theology is no less encumbered with ideological baggage. A significant number of liberation theologians have uncritically embraced the Marxist mythology of the class struggle and have thereby transformed the blessed hope into a kingdom of freedom, a classless society, which they identify with the biblical symbol of the kingdom of God. It is fashionable in these circles to reconceive God as “the power of the future,” “the event of self-liberating love,” “the dynamic of history,” and “the ever-open horizon leading to creativity.”

Liberation theology rightly calls our attention to the plight of the poor and reminds us of an often neglected dimension of the gospel—that Jesus came to free the oppressed. But by its tendency to read the biblical texts in the light of Marxist ideology, it succumbs to the ideological spell, which prevents it from perceiving the full reality of the situation. The excesses of Marxist regimes are treated with the same delicate constraint that characterizes the reactions of ideological rightists to the sins of the military-industrial complex. In each case, there are toes on which it is considered inappropriate to tread.

Like the German Christians, all the above movements appeal to new sources of revelation in addition to Holy Scripture. The working of God in nature and universal history becomes just as, if not more, important than God’s self-disclosure in the Bible. Cultural and religious experience has more significance than the definitive self-revelation of God in Jesus Christ. Even the Religious Right, which is ostensibly evangelical, is prone to treat the founding documents of our nation, the Constitution and Declaration of Independence, as divinely sanctioned though secondary sources of authority for faith and life.

Revival Or Religiosity?

Given these contemporary ideological distortions of the faith, we need to consider whether our cultural and religious situation on the whole ominously recalls the prewar Nazi period in Germany. I believe that Arthur Cochrane’s perceptions must be taken seriously, for though there is much in America’s cultural experience today that is novel and different, there is also much that is disturbingly familiar.

There is no question that there is a revival of interest in religion today just as there was in Germany in the later 1920s and 1930s. But is this revival one of religiosity only, or can we sense the working of the Holy Spirit? Are we closer to England in Wesley’s time or to Germany in Hitler’s time? A true revival will be united with a passion for social righteousness. It will bear fruit in charitable enterprises and social reform. The evangelical awakenings in eighteenth-century England and Wales remolded English society to a remarkable extent and, according to some historians, staved off the kind of violent revolution that devoured France.

Does the upsurge of religious sentiment in our day contain a vision of social righteousness in the biblical sense, or is it basically ideological in its thrust, intent on keeping the privileged classes in power? Are the tens of thousands who flock to the mass religious rallies (associated with such names as Jimmy Swaggart, Jim Bakker, and John Gimenez) genuinely convicted of sin, or are they only confirmed in their biases? In the revivals of Jonathan Edwards, people often wept and implored God for mercy. Nowadays they clap their hands and shout “amen,” showing their agreement with what is being said.

I am not as pessimistic as some of my colleagues. I discern a genuine moving of the Spirit in our times. The despairing are being given hope, the sick are being healed, the hungry are being fed (as in Operation Blessing of the “700 Club”). Yet whether this will eventuate in a genuine revival depends very much on whether organized religion, both evangelical and liberal, can free itself from its bondage to cultural ideology and become truly prophetic—in the tradition of the biblical prophets and Reformers.

If religion shields us from the pressing social issues of our time—the growing disparity between rich and poor, the continued reliance of the big powers on weapons of mass extermination, unrestricted abortion, the break-down of the family, the pollution of the environment, world hunger—then it will serve only to shore up vested interests in society. But if it awakens us to the reality of social evil as well as personal sin, it will then prove to be transformative, and our culture will be given a new lease on life. A revival that would result in the reform of the church as well as the transformation of society could be the hope of both the church and the world.