In this fall’s Agnes of God, an agonizing shriek and a newborn child found strangled under a nun’s bed set the stage for the indignant questions of a court-appointed psychiatrist. The government wanted Dr. Martha Livingston (Jane Fonda) to determine whether Sister Agnes (Meg Tilly) was sane enough to stand trial for the murder. Livingston wanted to know more: how a novice became pregnant and why it was kept secret.

Mentally drifting through Livingston’s inquisition, Agnes displayed the spaced-out sweetness of a newly converted Moonie. We could only root for a quick deprogramming. As Livingston told Mother Miriam Ruth (Anne Bancroft): “She has a right to know there’s a world out there filled with people who … fall in love, have babies, and occasionally are very happy.”

Agnes was a serious film about serious choices. Doubt, level-headed faith, and mysticism were each given their articulate moments. In a time when the roar of Rambo weapons, Mad Max vehicles, and Star Wars special effects have all but drowned out dialogue in the cinema, the human voice speaking from the heart and soul deserves our applause.

The film worked as a dramatization of philosophies in conflict, but it also worked as a mystery story—complete with hidden clues, silent witnesses, and a secret passageway. What distinguished it from other films of the genre is that the mystery really matters. We were pulled along not only by who-done-it curiosity but by a desire to know if God is really present, if miracles really happen.

Miracles

The miracles this film focused on, however, are very specialized: heavenly voices, a virgin birth, and stigmata—the marks resembling Jesus’ crucifixion wounds some medieval mystics were said to have received.

From a Protestant point of view, God was terribly confined in Agnes’s world. He had to squeeze into modern times through her bleeding palms and through mysterious conception or not be seen at all. Agnes’s ecstatic singing, we were told, is all that keeps Mother Miriam’s faith alive amid the contemporary dearth of saints.

One couldn’t help longing for the God who saves marriages, calms anger, clarifies perplexities, and even helps us find our lost keys.

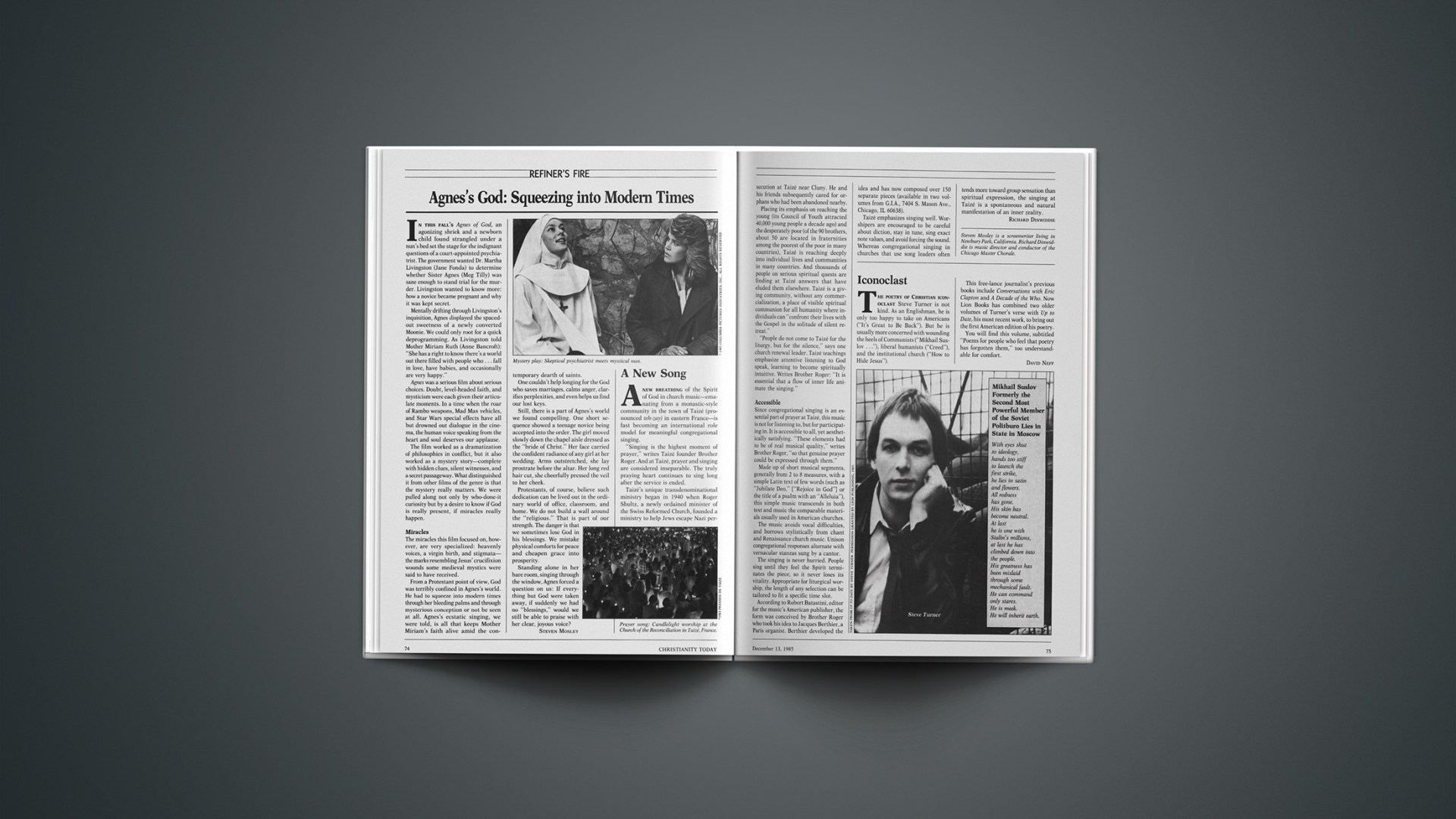

Still, there is a part of Agnes’s world we found compelling. One short sequence showed a teenage novice being accepted into the order. The girl moved slowly down the chapel aisle dressed as the “bride of Christ.” Her face carried the confident radiance of any girl at her wedding. Arms outstretched, she lay prostrate before the altar. Her long red hair cut, she cheerfully pressed the veil to her cheek.

Protestants, of course, believe such dedication can be lived out in the ordinary world of office, classroom, and home. We do not build a wall around the “religious.” That is part of our strength. The danger is that we sometimes lose God in his blessings. We mistake physical comforts for peace and cheapen grace into prosperity.

Standing alone in her bare room, singing through the window, Agnes forced a question on us: If everything but God were taken away, if suddenly we had no “blessings,” would we still be able to praise with her clear, joyous voice?

STEVEN MOSLEY

A New Song

A new breathing of the Spirit of God in church music—emanating from a monastic-style community in the town of Taizé (pronounced teh-zay) in eastern France—is fast becoming an international role model for meaningful congregational singing.

“Singing is the highest moment of prayer,” writes Taizé founder Brother Roger. And at Taizé, prayer and singing are considered inseparable. The truly praying heart continues to sing long after the service is ended.

Taizé’s unique transdenominational ministry began in 1940 when Roger Shultz, a newly ordained minister of the Swiss Reformed Church, founded a ministry to help Jews escape Nazi persecution at Taizé near Cluny. He and his friends subsequently cared for orphans who had been abandoned nearby.

Placing its emphasis on reaching the young (its Council of Youth attracted 40,000 young people a decade ago) and the desperately poor (of the 90 brothers, about 50 are located in fraternities among the poorest of the poor in many countries), Taizé is reaching deeply into individual lives and communities in many countries. And thousands of people on serious spiritual quests are finding at Taizé answers that have eluded them elsewhere. Taizé is a giving community, without any commercialization, a place of visible spiritual communion for all humanity where individuals can “confront their lives with the Gospel in the solitude of silent retreat.”

“People do not come to Taizé for the liturgy, but for the silence,” says one church renewal leader. Taizé teachings emphasize attentive listening to God speak, learning to become spiritually intuitive. Writes Brother Roger: “It is essential that a flow of inner life animate the singing.”

Accessible

Since congregational singing is an essential part of prayer at Taizé, this music is not for listening to, but for participating in. It is accessible to all, yet aesthetically satisfying. “These elements had to be of real musical quality,” writes Brother Roger, “so that genuine prayer could be expressed through them.”

Made up of short musical segments, generally from 2 to 8 measures, with a simple Latin text of few words (such as “Jubilate Deo,” [“Rejoice in God”] or the title of a psalm with an “Alleluia”), this simple music transcends in both text and music the comparable materials usually used in American churches.

The music avoids vocal difficulties, and borrows stylistically from chant and Renaissance church music. Unison congregational responses alternate with vernacular stanzas sung by a cantor.

The singing is never hurried. People sing until they feel the Spirit terminates the piece, so it never loses its vitality. Appropriate for liturgical worship, the length of any selection can be tailored to fit a specific time slot.

According to Robert Batastini, editor for the music’s American publisher, the form was conceived by Brother Roger who took his idea to Jacques Berthier, a Paris organist. Berthier developed the idea and has now composed over 150 separate pieces (available in two volumes from G.I.A., 7404 S. Mason Ave., Chicago, IL 60638).

Taizé emphasizes singing well. Worshipers are encouraged to be careful about diction, stay in tune, sing exact note values, and avoid forcing the sound. Whereas congregational singing in churches that use song leaders often tends more toward group sensation than spiritual expression, the singing at Taizé is a spontaneous and natural manifestation of an inner reality.

RICHARD DINWIDDIE

The poetry of Christian iconoclast Steve Turner is not kind. As an Englishman, he is only too happy to take on Americans (“It’s Great to Be Back”). But he is usually more concerned with wounding the heels of Communists (“Mikhail Suslov …”), liberal humanists (“Creed”), and the institutional church (“How to Hide Jesus”).

This free-lance journalist’s previous books include Conversations with Eric Clapton and A Decade of the Who. Now Lion Books has combined two older volumes of Turner’s verse with Up to Date, his most recent work, to bring out the first American edition of his poetry.

You will find this volume, subtitled “Poems for people who feel that poetry has forgotten them,” too understandable for comfort.

DAVID NEFF

Mikhail Suslov Formerly the Second Most Powerful Member of the Soviet Politburo Lies in State in Moscow

With eyes shut to ideology, hands too stiff to launch the first strike, he lies in satin and flowers. All redness has gone. His skin has become neutral. At last he is one with Stalin’s millions, at last he has climbed down into the people. His greatness has been mislaid through some mechanical fault. He can command only stares. He is meek. He will inherit earth.