The Protestant Reformation broadened enormously the scope of Christian worship. Priests were no longer needed as mediators between God and worshipers. Common labor and the creative efforts of the Christian’s hands could become consecrated offerings: praise and thanksgiving, simply on the basis of the spirit and manner in which they were offered. Said Max Weber, “All the world became a cathedral and every believer a priest.”

And so it has continued. Modem evangelicals take to heart Saint Paul’s admonition that everything they do should resound to the glory of God (1 Cor. 10:31). That includes work and play in worldly environments just as surely as hymns and prayers in the sanctuary. Ask good Presbyterians the old catechismal query, “What is the chief end of man?” and they likely will respond, “To glorify God and enjoy him forever.”

Likewise, ask evangelical athletes, “Why do you play sports?” and there is a good chance they will echo the words of former Pittsburgh Pirate Manny Sanguillen: “I just want to glorify God, that’s why I play ball.”

Clearly, the most remarkable mix of sport and religion has been managed at the highest, professional levels of competition. Ecclesio-jock organizations, such as Fellowship of Christian Athletes and Pro Athletes Outreach, flourish. Informal Bible studies for players and their wives are commonplace. Most professional football teams have ad hoc chaplains. Humorist Roy Blount, Jr., claims that so many Christians have invaded big-time football that, when he set out to select an “All-Religious Team” and an “All-Heathen Team,” he couldn’t find enough heathens to field a squad.

This trend among evangelical athletes may be the beginning of a genuine revitalization of religious ritual in sport. But I am not optimistic that it will stimulate a much-needed rethinking of the meaning of sport among the evangelical community in general.

Competition As Worship?

The chances that that will happen are not good, for one very critical reason. In presuming to appropriate sport as a ritualistic medium—games played “to the glory of God”—the Christian athletes confront an inevitable contradiction.

Sport, which celebrates the myth of success, is harnessed to a theology that often stresses the importance of losing. Sport, which symbolizes the morality of self-reliance and teaches the just rewards of hard work, is used to propagate a theology dominated by the radicalism of grace (“The first shall be the last and the last first”). Sport, a microcosm of meritocracy, is used to celebrate a religion that says all are unworthy and undeserving.

In addition, church tradition and the Scriptures quite clearly teach the importance of purity in the actions offered as rituals of worship. The New Testament Christians were just as concerned about the acceptability of their symbolic offerings as the Old Testament priests and prophets were about the purity of their animal sacrifices. Christians would not think of consecrating acts of robbery or murder as worship, nor would they condone worshipers enacting the liturgy while haboring feelings of jealousy, hate, or a thirst for revenge.

Yet anyone close to the sports scene knows that competition, even between the most amiable opponents, often becomes a rite of unholy unction, a sacrament in which aggression is vented, old scores settled, number one taken care of, and where the discourteous act looms as the principal liturgical gesture. Even in contests played in the shadow of church walls—the church league softball or basketball game—tempers can flare and the spiritual graces of compassion and sensitivity can place second to “winning one for good ol’ First Baptist.”

The psychological dimension of competition has always been a touchy subject among evangelicals, most of whom downplay its importance in the competitive process. And they do so for good reason. Any objective appraisal of the competitive process will reveal that it is driven by the spirit of self-promotion. This is not an anomaly or a description of the competitive urge gone berserk. This is the way it has to be.

Self-promotion is the lifeblood of competitive games. Those who would give the game an honest try (and this is widely held to be a spiritual duty of the Christian athlete) must make a sincere effort to win. And within the context of the game, “trying to win” means promoting one’s own (or the team’s) interest at the expense of the opponent’s interest.

In a spirited but frank defense of competition, sailor Stuart Walker avowed that good competitors should “feel no concern for the opinion and feelings of others.…” The lack of concern for the feelings of competitors is useful because it eliminates a distraction. “If you don’t care what the other fellow thinks, you can tack on him wherever you wish.”

God, the Boxer

Boxer Floyd Patterson credited the Lord for helping him flatten Archie Moore to win the heavyweight championship. “I could see his eyes go glassy as he fell back,” said Patterson, “and I knew if he got up again it wouldn’t do him any good. I just hit him and the Lord did the rest.”

Tennis, Anyone?

As a way of underscoring the common sense in Walker’s philosophy, consider a sympathetic tennis player. Constantly worried about the detrimental effects of her serve on her opponent’s performance, and in a gesture of sympathy and good will, she decreases the ball’s velocity and spin, and places it conveniently in the center of the service area. Not only would she win few championships, she would be ridiculed (even by her opponent) as a dangerous subversive, a spoilsport who violated the unwritten contract by not giving the game an honest try.

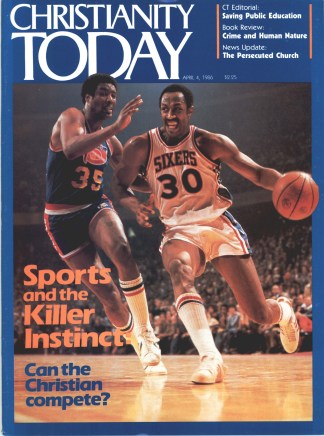

Just as surely as sympathetic instincts can douse the fires of competition, a cool, calculated insensitivity toward opponents can fan them into a blaze. The so-called killer instinct is widely believed to be indispensable for athletic success. In an analysis of winning and losing attitudes among athletes, sport psychologist Bruce Ogilvie reported: “Almost every truly great athlete we have interviewed during the last four years … has consistently emphasized that in order to be a winner you must retain the killer instinct.”

Some coaches and players do not settle for mere affectlessness; how much better feelings of sympathy can be controlled if opponents are viewed as dangerous enemies. Jimmy Connors’s meteoric rise to the top in professional tennis was accompanied by a brash demeanor that shocked the staid tennis aristocracy. He berated officials, made obscene gestures, and openly chided his opponents. Said Connors: “Maybe my methods aren’t socially acceptable to some, but it’s what I have to do to survive. I don’t go out there to love my enemy, I go out there to squash him.”

Even coaching legend Vince Lombardi saw the need to conjure up “competitive animosity” toward the opponent during the week before the big game. This belief was captured in his oft-quoted remark, “To play this game you must have that fire in you, and nothing stokes that fire like hate.”

There is clinical evidence to show that Vince was not just talking through his helmet. In a study of differences between habitually successful and unsuccessful competitors, Francis Ryan, former psychologist and track coach at Yale, discovered that good competitors viewed their opponents as temporary enemies. But poor competitors, “rather than whipping up their anger to meet the competitive challenge, did everything possible to maintain an atmosphere of friendliness with their opponents.…”

Locker-Room Religion

Athletes have not found it easy to combine Christian spirituality and winning competitiveness. Asked how he blended football with faith, former Cincinnati Bengal Ron Pritchard said, “As far as being challenged physically, I’m probably not at the point where I can turn the other cheek all the time. I’d like to be able to say, ‘Hey, God loves you and I love you, and I’ll see you later.’ But I’m not there yet; but with God’s help, I’ll make it some day.”

Doug Plank, formerly a hard-hitting defensive back for the Chicago Bears, called his athletic and religious life a paradox: “As a Christian I learn to love, but when the whistle blows I have to be tough. You’re always walking a tightrope.” The trick to walking the tightrope (which few seem to have mastered) is to temper competitive enthusiasm with just the right amount of spiritual grace, igniting the necessary competitive fire without marring one’s Christian witness.

This is the plight of evangelical athletes. They want very much to ritualize their performances as acts of worship. Yet they are not entirely sure that sport is worthy of sacred offering, and even less certain about the competitive social dynamic in which it is embedded. The question nags at the subconscious: Is sport a tribute or a temptation, a unique liturgy to symbolize Christian devotion or a close brush with perversity? Is it a “rite” or a “wrong”?

In a desperate attempt to harmonize these clashing elements of ritual, evangelicals have concocted a locker-room religion. It is not so much orthodox evangelicalism as a hodgepodge of biblical truths, worn-out coaching slogans, Old Testament allusions to religious wars, and interpretations of Paul’s metaphors that would drive the most straight-laced theologian to drink.

The most popular doctrine in this locker-room religion is “Total Release Performance,” promulgated throughout the evangelical network by the Institute for Athletic Perfection. “The quality of an athlete’s performance can reveal the quality of his love for God,” says IAP president Wes Neal. The quality most valued is intensity, the same kind of intensity that Jesus had—“His total concentration toward accomplishing his Father’s purpose.”

Total Release Performance (initiates refer to it simply as TRP) has become a familiar watchword for evangelical athletes, a ritual for identifying the faithful. Shouted across lines of scrimmage or whispered in the huddle, TRP is a cosmic energizer, the athletic equivalent of the Pentecostal’s “Praise the Lord” or the Baptist’s “Amen.”

So forcefully has the doctrine behind the motto shaped the beliefs of Christian athletes, they rarely talk about sport as worship without mentioning the critical contingency of total release. Pro footballer Archie Griffin painted crosses on his shoes and wristbands as a reminder that he was playing to glorify Christ and not himself. “All you can ask of yourself is that you give 110 percent. I want to please Christ, and I can’t be happy if I’m giving any less than that,” Griffin said.

Love and intensity of play often are coupled with thankfulness, taking the form of “Praise Performances,” the purpose of which is to “express your love and gratitude to God for who he is and what he has done.” Belting another person around on a football field may seem an odd way to express your love to him or to the Almighty. But in what may be the most puzzling theological conundrum to come out of the movement, former Los Angeles Ram Rich Saul once warned his Christian opponents, “I’m going to hit you guys with all the love I have in me.”

Grahams Of The Gridiron

Another way evangelicals have sought to sanctify competitive sport has been to view it through the finely ground lenses of utilitarianism. They concentrate on the evangelistic potential of sport. In a society that attaches inordinate significance to competitive success, winning in athletics offers a visible platform from which athletes can publicly declare their witness.

Record-setting Walter Payton of the Chicago Bears says, “I realized in my second year that for me, performing well on the field and doing well as a professional football player made little kids look up to me. God enabled me to communicate with them. I found out that this was the way Christ wanted me to spread his message. My professional performance is God’s way of using me to reach out and touch kids and bring them to Christ.”

Turning in stellar individual performances, as Payton consistently does, certainly increases his evangelistic potential. It was raised even higher when the Bears put together a Super Bowl season. As Roger Staubach, reflecting on the Cowboy’s win over Miami in the 1972 Super Bowl, said: “I had promised that it would be for God’s honor and glory, whether we won or lost. Of course the glory was better for God and me since we won, because the victory gave me a greater platform from which to speak.”

But by using sport as a net to catch sinners’ souls, the evangelicals exacerbate rather than assuage the nagging conflicts. When sport is harnessed to the evangelistic enterprise, evangelicals become as much endorsers of the myths reinforced by popular sport (“winning is everything”) as they do of the Christian gospel.

The contradictions notwithstanding, theologizing about sport as religious worship obviously has helped evangelicals come to grips with their involvement in a social institution that enjoys a rather awkward relationship to the Christian gospel. But one has to wonder why they have chosen to organize their worship ritual around evangelism and a rather minor ethical concept (the Christian responsibility to work diligently). This is done while ignoring theological constructs that could more securely link the ritual to Christian theology.

Why, for example, haven’t evangelicals organized the athletic liturgy around the principle of grace, the fundamental Christian doctrine that teaches that humankind was secured by God in an act of unmerited favor? Surely no doctrine lies closer to the heart of historic Christianity. Or why haven’t they considered sport as an expression of the divine spark called play, and ritualized it as a celebration of humanity’s status in the divine order? Where else but at play can we exude what Father Hugo Rahner called “a lightness and freedom of the spirit, an instinctively unerring command of the body, a certain neatness and graceful nimbleness of mind and movement” through which we might “participate in the divine” and achieve “the intuitive imitation and the still earthbound recovery of an original unity [we] once had with the One and the Good.” What a dramatic departure from the meritocratic glorification of human effort that undergirds the doctrine of Total Release Performance.

Pilgrim of Plod

In researching a best-selling book on running, the late Jim Fixx was struck by the way devotees described their commitment to the sport as a “conversion experience.” The wife of one pilgrim of plod told him: “Tom used to be a Methodist; now he’s a runner.”

Glimmers Of A Christian Sport Ethic

It is hard not to be suspicious, not so much of sincere Christian athletes who say they worship through sport, but of a sports establishment which, more than anyone else, seems to benefit when sports are appropriated as religious ritual. In his book Identity and the Sacred, Hans J. Mol noted that social institutions typically sacralize (that is, attribute sacred significance to) beliefs and values regarded as essential for the group’s survival. In the jungles of high-level competition, it is no secret that survival depends on winning, and somehow it seems too happy a coincidence that giving an all-out effort is considered to glorify God but also helps you win championships. Or that winning improves one’s evangelistic potential and moves your team up in the standings.

There is, of course, a way out for evangelicals, a way they can more closely align their athletic rituals to the devotion and beliefs they wish to express. There is a way to cancel (or at least lessen) inherent contradictions between faith and action, belief and liturgy, a way to insure that the seeds of the movement will lead to a reconceptualization of the meaning of sport in the Christian life. This would quite obviously require Christians to build a new sports ethic from the ground up, an ethic that places a premium on the Christian distinctives of submitting ends to means, product to process, quantity to quality, caring for self to caring for others.

Here are a few thoughts—a start, perhaps—about what a Christian sports ethic might look like.

First, we should recognize that against the backdrop of the contemporary sport ethic, sport conduct that has as its basis the Christian ethic is likely to be viewed as irrational. Don’t expect a Christian ethic to fit snugly inside the reigning secular ethic.

Second, we must recognize that sport is, by its very competitive nature, a delicate interpersonal experience. From a human relations standpoint, sport represents a series of catastrophes that are narrowly averted at each point in the game. Only the prudent, the mature, the earnest, the self-controlled and the committed Christian can fully appreciate the true nature of sport.

Third, recognize that there is nothing like one’s play life to make one transparent. Plato once said you can learn a lot more about an individual in an hour of play than in a year of conversation. Be prepared to deal with those character flaws that are brought to the surface during the excitement of the contest. Do not dismiss them as part of the game; they are the true person.

Fourth, recognize that if sport is to be sport at all, the objective of winning must not be de-emphasized. The prospect of winning lies at the very heart of competitive sport. Contests in which the prospects of winning have been forfeited are heartless, pointless encounters that lack purpose and incentive for the participants. The spoilsport who does not try to win is worse than a cheat. The cheat robs the game of its noble spirit; but the spoilsport steals its very heart. At the same time, however, we must be careful not to delude ourselves into thinking that God in any way cares about the outcome. Those who feel that God especially cherishes winners—or that a win somehow glorifies him more than a loss—have theologically reduced God to a spectator who sits on the sidelines caught up in the surprises of the contest.

Finally, although the objective of the contest is to win, the reason for participating far surpasses a concern for the actual outcome. Christians should play for one reason: to celebrate a joyous life, secure in Christ. Sports for the Christian should reflect none of the tension, aggravation, and maliciousness evident in secular sport. More than in any other aspect of his life, the play life of the Christian should be light-hearted; it should be a festive time in which the quality of play is enhanced simply because the game is a tribute to our Heavenly Father. The authentically Christian play attitude is rooted in Christ’s spirit, a spirit that flows from the collective souls of the players and is shared by those who watch. This attitude of play is possible only for those whose lives are secure in Christ, because only those who are secure in Christ can truly be light of heart and truly play.

Hugo Rahner, to mention his fine work again, seizes hold of Zechariah 8:5 as a standard we might use to judge our play. Zechariah 8:5 presents a vision of the coming messianic age, a vision in which the streets of the city are full of boys and girls playing. Playing, Rahner tells us, whether we conceive of it as an activity or a state of mind, is but a feeble and tentative imitation of what is in store for us in the blessed world to come. Think of it! Our play life can be an imitation of our life for all eternity. Would we be happy with our sport for an eternity, or should we begin changing it?

Dinner with Ogres

In the 1973 Fiesta Bowl, Pitt was to face Arizona State. The players were scheduled to attend a pregame steak fry as part of the bowl festivities. Arizona State coach Frank Kush was upset. “You can’t tell the kids that they’re going up against a bunch of ogres, then have them sit across the table from the opponents at a banquet and find out that they’re really pretty nice guys.”

SHIRL J. HOFFMAN1Shirl J. Hoffman is professor and chair of the Department of Physical Education at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro. He is at work on a book, Imaging the Divine: Sport and Play in Christian Experience, to be published by InterVarsity Press.

The Stadium as Cathedral

Play has not always been secularized.

There is evidence that suggests ball games played a role in Easter ceremonies of the Christian church during the twelfth century. At Vienne in the palace of the archbishop, after the formal Easter meal, the archbishop threw out a ball among the parishioners, who promptly engaged themselves in a ceremonial game.

Thus history proves that play can be a fundamental form of religious expression, a way of acting out symbolically what man has found impossible to express verbally.

To the twentieth-century mind, the idea of play and games as worship rituals is almost incredible. Play has been secularized too long. What we find so incredible is that something so frivolous and pleasurable as play could be integrally tied to the serious matter of worship.

Perhaps these early rituals would be more palatable to our postindustrial minds if they resulted in fields being planted or a building being constructed—something of utility and substance produced. Then we might see more clearly the connection with worship. But this would be to misunderstand the nature and spirit of worship.

True worship is unproductive, nonutilitarian. A worshipful attitude is an attitude caught up in adoration and praise and celebration. It seeks nothing. It is, by human standards, a wasteful procedure. “The offering of the best of the herd or the giving up of the first fruits are acts completely antithetical to the principle of [productive activities such as] work and labor,” writes one scholar. Worship is pursued for its own intrinsic benefits.

Worship also is something we engage in voluntarily, a matter of free choice and free will. One cannot be forced to worship in a meaningful way any more than one can be forced to play. There is also a way in which worship transports one to a world that transcends the mundane, profane world that surrounds him. We are able to worship effectively only to the extent that we allow the temporal and spatial limits of the service to bind us, and we “pretend” that the cares and concerns of our work lives have been eliminated.

Worship also exists in our leisure time, the time not allocated for work. German philosopher Josef Pieper contends that leisure is possible and justifiable only in its relation to celebration of divine worship. Leisure, Pieper asserts, is not merely free time, it is a mental and spiritual attitude of “nonbusyness,” of inward calm and peace. It is not only the occasion, but the capacity for steeping oneself in the whole of creation. It is leisure that leads man to accept the reality of creation and thus to celebrate it.

These structural similarities between worship and play may point us in a good direction for reforming sport. The integration of sport and genuine Christianity is possible only when we recognize the potential for sport as a celebrative and worshipful act. (And not simply as a platform for evangelism or the building of character.) Play can be an expression of inner calm, a peace-inaction known only to those who have understandable cause (the grace of God) for celebration.

Sport at its best, in fact, may be open especially to the Christian. Why? Because the Christian is a person who can anticipate eternity, who is somehow poised between gaiety and gravity, who in his playing gains an appreciation of what it means to be in the world but not of the world.

SHIRL HOFFMAN