“I expected 90 percent of the art would portray prison themes—picturing confinement, loneliness, and depression,” says Donald Smarto of the works submitted to the Justice and Mercy Juried Art Contest of Inmate Art. “But,” concludes the director of the Wheaton, Illinois, Institute for Prison Ministries, “most of it portrays things an inmate doesn’t ordinarily see.”

“They show a longing for a world outside—often the world of nature—at times bordering on a utopian concept of what might be,” adds Alva Steffler, professor of art at Wheaton College and one of the show’s judges.

Smarto was planning a national conference on prison ministries for July 1986 when he “realized that the one group of people who were not going to be here was the prisoners themselves. I asked, ‘How can we represent them?’ So I suggested an inmate art competition.”

Out of 150 submissions in a variety of media, 20 were awarded prizes by three judges: Smarto, Steffler, and James Stambaugh, director of the Billy Graham Center Museum. The winning entries were purchased and are now a permanent part of the institute’s collection.

Surprises

As the art began arriving, Smarto was in for some surprises: “The art was far better than I thought it would be,” he says. “I was expecting things that would be crude, but it is well-executed, sophisticated art.”

Steffler agrees: “The quality is quite high. There is a commitment to a lot of careful work by some of these inmates.”

When some inmates saw the Billy Graham Center’s name on the brochure, they chose religious themes. But the specifically religious art was largely disappointing to Smarto. “Poorly done,” he comments. “Oversentimental and gushy.”

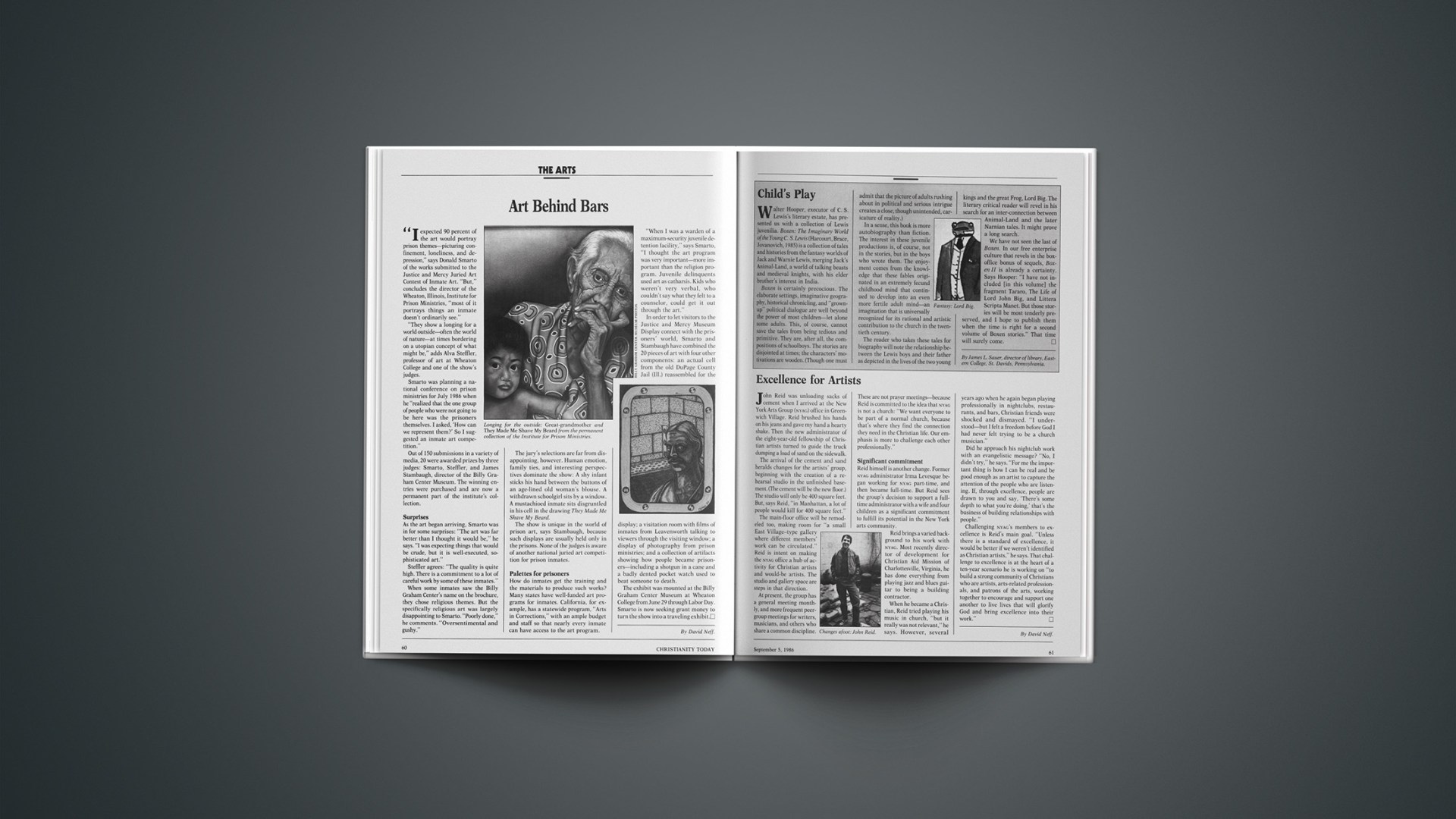

The jury’s selections are far from disappointing, however. Human emotion, family ties, and interesting perspectives dominate the show: A shy infant sticks his hand between the buttons of an age-lined old woman’s blouse. A withdrawn schoolgirl sits by a window. A mustachioed inmate sits disgruntled in his cell in the drawing They Made Me Shave My Beard.

The show is unique in the world of prison art, says Stambaugh, because such displays are usually held only in the prisons. None of the judges is aware of another national juried art competition for prison inmates.

Palettes For Prisoners

How do inmates get the training and the materials to produce such works? Many states have well-funded art programs for inmates. California, for example, has a statewide program, “Arts in Corrections,” with an ample budget and staff so that nearly every inmate can have access to the art program.

“When I was a warden of a maximum-security juvenile detention facility,” says Smarto, “I thought the art program was very important—more important than the religion program. Juvenile delinquents used art as catharsis. Kids who weren’t very verbal, who couldn’t say what they felt to a counselor, could get it out through the art.”

In order to let visitors to the Justice and Mercy Museum Display connect with the prisoners’ world, Smarto and Stambaugh have combined the 20 pieces of art with four other components: an actual cell from the old DuPage County Jail (Ill.) reassembled for the display; a visitation room with films of inmates from Leavenworth talking to viewers through the visiting window; a display of photography from prison ministries; and a collection of artifacts showing how people became prisoners—including a shotgun in a cane and a badly dented pocket watch used to beat someone to death.

The exhibit was mounted at the Billy Graham Center Museum at Wheaton College from June 29 through Labor Day. Smarto is now seeking grant money to turn the show into a traveling exhibit.

By David Neff.

Child’s Play1By James L. Sauer, director of library, Eastern College, St. Davids, Pennsylvania.

Walter Hooper, executor of C. S. Lewis’s literary estate, has presented us with a collection of Lewis juvenilia. Boxen: The Imaginary World of the Young C. S. Lewis (Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1985) is a collection of tales and histories from the fantasy worlds of Jack and Warnie Lewis, merging Jack’s Animal-Land, a world of talking beasts and medieval knights, with his elder brother’s interest in India.

Boxen is certainly precocious. The elaborate settings, imaginative geography, historical chronicling, and “grownup” political dialogue are well beyond the power of most children—let alone some adults. This, of course, cannot save the tales from being tedious and primitive. They are, after all, the compositions of schoolboys. The stories are disjointed at times; the characters’ motivations are wooden. (Though one must admit that the picture of adults rushing about in political and serious intrigue creates a close, though unintended, caricature of reality.)

In a sense, this book is more autobiography than fiction.

The interest in these juvenile productions is, of course, not in the stories, but in the boys who wrote them. The enjoyment comes from the knowledge that these fables originated in an extremely fecund childhood mind that continued to develop into an even more fertile adult mind—an imagination that is universally recognized for its rational and artistic contribution to the church in the twentieth century.

The reader who takes these tales for biography will note the relationship between the Lewis boys and their father as depicted in the lives of the two young kings and the great Frog, Lord Big. The literary critical reader will revel in his search for an inter-connection between Animal-Land and the later Narnian tales. It might prove a long search.

We have not seen the last of Boxen. In our free enterprise culture that revels in the box-office bonus of sequels, Boxen II is already a certainty. Says Hooper: “I have not included [in this volume] the fragment Tararo, The Life of Lord John Big, and Littera Scripta Manet. But those stories will be most tenderly preserved, and I hope to publish them when the time is right for a second volume of Boxen stories.” That time will surely come.