Will Campbell—unconventional Southern Baptist preacher and the widely acclaimed author of Brother to a Dragonfly—published his third novel in September. With The Convention, he peers into the future of the Southern Baptist Convention and imagines that the tensions within it have led to the reorganization of the denomination. It becomes the Federal Baptist Church, and it is dominated by fundamentalists closely allied with right-wing political leaders. That scenario is not too flattering to today’s conservatives, but moderate Southern Baptists are not the heroes of the book either. As one of Campbell’s characters laments, “Not enough moderates or fundamentalists care about where we Baptists came from.”

Indeed, Southern Baptists are engaged in a struggle—perhaps to the death—over their identity. Conservatives within the convention believe it forgot where it came from when it became too loose and easy about its theology, especially its theology about the authority of the Bible. Moderates believe the convention forgot where it came from when it began fighting about the precise definition of doctrines and hedging on the Baptist hallmark of individual soul competency, which holds that each person is able to understand truth and live by it before God. Yet many other Southern Baptists, like Campbell, eschew the labels “conservative” and “moderate” and say the denomination forgot where it came from when it got enmeshed in power politics and obscured the simple, straightforward concentration of its laity on evangelism and missions.

In a sense, then, this still-burgeoning denomination is like a teenager sliding uneasily into adolescence—full of conflicting impulses, overcome with vitalities both exciting and disconcerting, uncertain what he will be tomorrow because he is unsure what “self” to claim from the past. The beleaguered teenager is confused, but only he can pronounce with any degree of authority what his future will be.

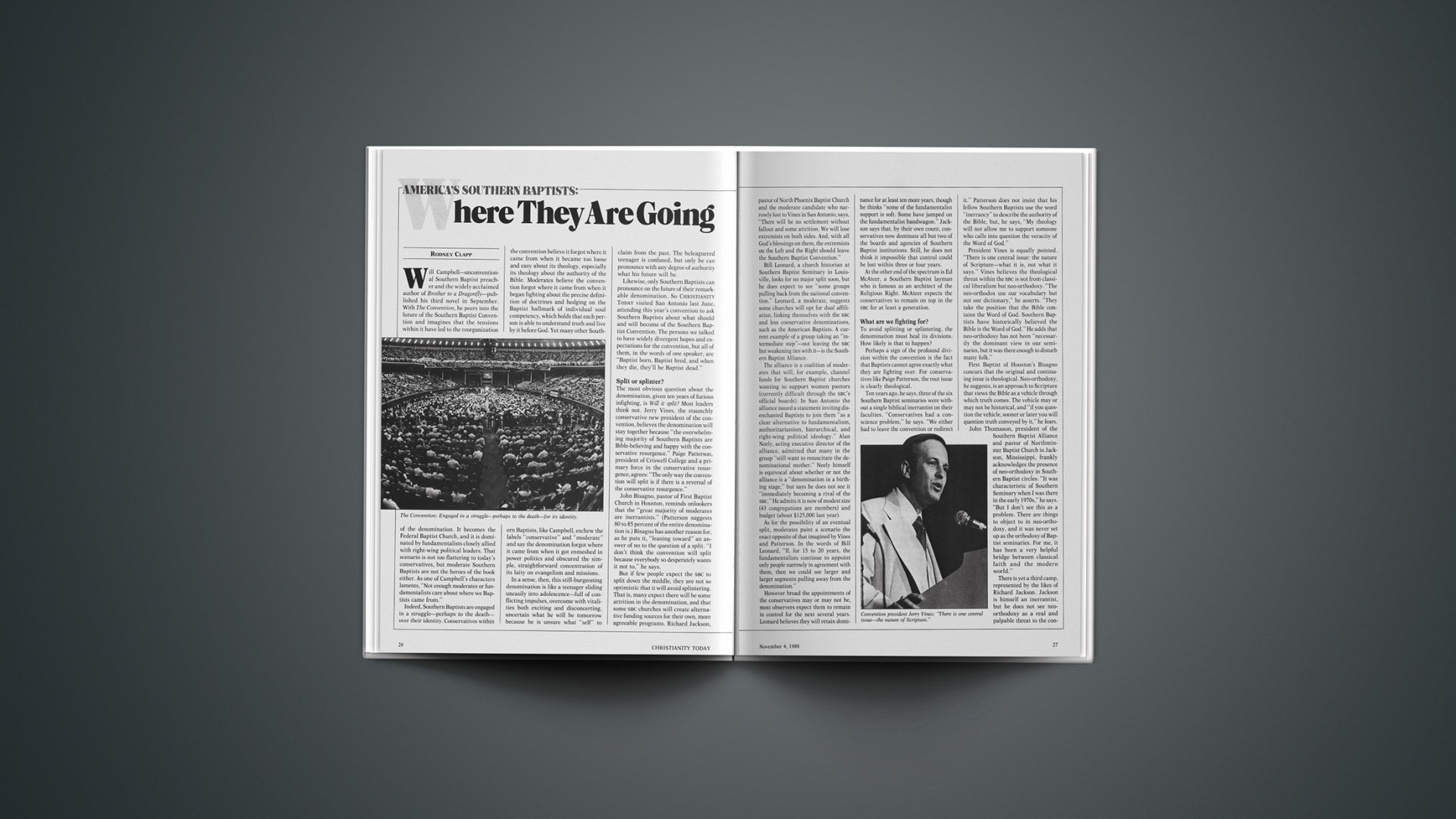

Likewise, only Southern Baptists can pronounce on the future of their remarkable denomination. So CHRISTIANITY TODAY visited San Antonio last June, attending this year’s convention to ask Southern Baptists about what should and will become of the Southern Baptist Convention. The persons we talked to have widely divergent hopes and expectations for the convention, but all of them, in the words of one speaker, are “Baptist born, Baptist bred, and when they die, they’ll be Baptist dead.”

Split Or Splinter?

The most obvious question about the denomination, given ten years of furious infighting, is Will it split? Most leaders think not. Jerry Vines, the staunchly conservative new president of the convention, believes the denomination will stay together because “the overwhelming majority of Southern Baptists are Bible-believing and happy with the conservative resurgence.” Paige Patterson, president of Criswell College and a primary force in the conservative resurgence, agrees: “The only way the convention will split is if there is a reversal of the conservative resurgence.”

John Bisagno, pastor of First Baptist Church in Houston, reminds onlookers that the “great majority of moderates are inerrantists.” (Patterson suggests 80 to 85 percent of the entire denomination is.) Bisagno has another reason for, as he puts it, “leaning toward” an answer of no to the question of a split. “I don’t think the convention will split because everybody so desperately wants it not to,” he says.

But if few people expect the SBC to split down the middle, they are not so optimistic that it will avoid splintering. That is, many expect there will be some attrition in the denomination, and that some SBC churches will create alternative funding sources for their own, more agreeable programs. Richard Jackson, pastor of North Phoenix Baptist Church and the moderate candidate who narrowly lost to Vines in San Antonio, says, “There will be no settlement without fallout and some attrition. We will lose extremists on both sides. And, with all God’s blessings on them, the extremists on the Left and the Right should leave the Southern Baptist Convention.”

Bill Leonard, a church historian at Southern Baptist Seminary in Louisville, looks for no major split soon, but he does expect to see “some groups pulling back from the national convention.” Leonard, a moderate, suggests some churches will opt for dual affiliation, linking themselves with the SBC and less conservative denominations, such as the American Baptists. A current example of a group taking an “intermediate step”—not leaving the SBC but weakening ties with it—is the Southern Baptist Alliance.

The alliance is a coalition of moderates that will, for example, channel funds for Southern Baptist churches wanting to support women pastors (currently difficult through the SBC’S official boards). In San Antonio the alliance issued a statement inviting disenchanted Baptists to join them “as a clear alternative to fundamentalism, authoritarianism, hierarchical, and right-wing political ideology.” Alan Neely, acting executive director of the alliance, admitted that many in the group “still want to resuscitate the denominational mother.” Neely himself is equivocal about whether or not the alliance is a “denomination in a birthing stage,” but says he does not see it “immediately becoming a rival of the SBC.” He admits it is now of modest size (43 congregations are members) and budget (about $125,000 last year).

As for the possibility of an eventual split, moderates paint a scenario the exact opposite of that imagined by Vines and Patterson. In the words of Bill Leonard, “If, for 15 to 20 years, the fundamentalists continue to appoint only people narrowly in agreement with them, then we could see larger and larger segments pulling away from the denomination.”

However broad the appointments of the conservatives may or may not be, most observers expect them to remain in control for the next several years. Leonard believes they will retain dominance for at least ten more years, though he thinks “some of the fundamentalist support is soft. Some have jumped on the fundamentalist bandwagon.” Jackson says that, by their own count, conservatives now dominate all but two of the boards and agencies of Southern Baptist institutions. Still, he does not think it impossible that control could be lost within three or four years.

At the other end of the spectrum is Ed McAteer, a Southern Baptist layman who is famous as an architect of the Religious Right. McAteer expects the conservatives to remain on top in the SBC for at least a generation.

What Are We Fighting For?

To avoid splitting or splintering, the denomination must heal its divisions. How likely is that to happen?

Perhaps a sign of the profound division within the convention is the fact that Baptists cannot agree exactly what they are fighting over. For conservatives like Paige Patterson, the root issue is clearly theological.

Ten years ago, he says, three of the six Southern Baptist seminaries were without a single biblical inerrantist on their faculties. “Conservatives had a conscience problem,” he says. “We either had to leave the convention or redirect it.” Patterson does not insist that his fellow Southern Baptists use the word “inerrancy” to describe the authority of the Bible, but, he says, “My theology will not allow me to support someone who calls into question the veracity of the Word of God.”

President Vines is equally pointed. “There is one central issue: the nature of Scripture—what it is, not what it says.” Vines believes the theological threat within the SBC is not from classical liberalism but neo-orthodoxy. “The neo-orthodox use our vocabulary but not our dictionary,” he asserts. “They take the position that the Bible contains the Word of God. Southern Baptists have historically believed the Bible is the Word of God.” He adds that neo-orthodoxy has not been “necessarily the dominant view in our seminaries, but it was there enough to disturb many folk.”

First Baptist of Houston’s Bisagno concurs that the original and continuing issue is theological. Neo-orthodoxy, he suggests, is an approach to Scripture that views the Bible as a vehicle through which truth comes. The vehicle may or may not be historical, and “if you question the vehicle, sooner or later you will question truth conveyed by it,” he fears. John Thomason, president of the Southern Baptist Alliance and pastor of Northminster Baptist Church in Jackson, Mississippi, frankly acknowledges the presence of neo-orthodoxy in Southern Baptist circles. “It was characteristic of Southern Seminary when I was there in the early 1970s,” he says. “But I don’t see this as a problem. There are things to object to in neo-orthodoxy, and it was never set up as the orthodoxy of Baptist seminaries. For me, it has been a very helpful bridge between classical faith and the modern world.”

There is yet a third camp, represented by the likes of Richard Jackson. Jackson is himself an inerrantist, but he does not see neo-orthodoxy as a real and palpable threat to the convention. “It’s almost as if people are saying we have to defend God and the Bible,” he says. “Is neo-orthodoxy rampant? It’s dead to theologians the world over.”

So for Jackson, the problem is “not really theological, it’s spiritual.” It is not difficult for academia to “get sterile” and begin to adjust theology to the lack of contact with the everyday, practical world. Many Southern Baptists moved north and created “y’all clubs,” Jackson adds, which became sterile because they were inbred. “We’ve all got to get off our seats and into the streets, witnessing to Jesus Christ.”

Bill Leonard offers a similar, but more complex analysis. Differences began to strain unity in the denomination when it became less culturally homogeneous. Yankees became Southern Baptists, and the South itself became more pluralistic. “We got cable television,” says Leonard. “We read magazines other than Southern Baptist magazines. Before, to marry ‘outside the faith’ meant to marry a Methodist, not a Muslim.”

Leonard believes these cultural pressures created a strain on the theological compromises cobbled so carefully by old denominational loyalists such as Herschel Hobbs, president of the convention in 1962–63. “The genius of the SBC,” Leonard says, “was that it developed statements of faith that followed Baptist doctrines but refused to define them so precisely that they alienated people. So some of the statements require affirmation of biblical authority, of eschatology and ecclesiology, but with no theories of any of these.”

Just As They Are

Nancy Hastings Sehested

One of the first women to serve as senior pastor in the SBC.

Memphis, Tennessee

Generations of Southern Baptists: Four

Have you ever denied or wanted to deny being a Southern Baptist?

It is embarrassing to be a Southern Baptist these days. The way that minorities, laypeople, and women are treated is appalling. The current controversy within the SBC is tragic.

When are you most proud to be Southern Baptist?

When I hear of missionaries, like Lillian Isaacs, who opened doors for many people through her literacy work.

On growing up Southern Baptist:

My Southern Baptist family gave me a strong biblical foundation. The Bible continues to mediate life to me, and challenge and strengthen me as a follower of Jesus.

Southern Baptists put me on an incredible journey to open the Bible.

Khomeini And The Convention

Now that conservatives have, in a manner of speaking, called the bluff on the less-precise statements that held the denomination together, the convention seems divided between those who refer primarily to inerrancy (though they often protest that the word itself need not be employed) and those who refer primarily to “characteristic Baptist beliefs,” such as soul competency and the priesthood of all believers. Moderates fear the conservatives are authoritarian and jeopardize soul competency. Conservatives insist that the accusation is a smoke screen.

Vines calmly observes that the “Bible is essential. Soul competency is derived from Scripture, not the other way around.” As Bisagno puts it, “Soul competency and the priesthood of all believers are well and good. But there are parameters. We don’t have Mormons teaching in our seminaries.” Patterson phrases the matter more sharply: “Competency of the soul and the priesthood of believers cannot mean you can believe anything and be a Southern Baptist. The Ayatollah Khomeini’s not going to teach at Southwestern Seminary.”

Yet some fear that Patterson and his colleagues have a yen for power not totally unlike that of Khomeini. Richard Jackson, tending again to look for a “spiritual” rather than a “theological” problem, candidly suggests, “Power is a heady wine to drink. There are a few—a very few—power brokers, and if they would just be quiet for two or three years, this thing would be over.” Referring to the prominent layman Paul Pressler and to Patterson, Jackson says, “It would help if the judge from Houston would stay in Houston and the educator from Dallas would stay in Dallas.”

All said, then, there is mixed optimism at best about the healing of Southern Baptist dividing points anytime soon. A worried Bisagno admits, “Maybe my dream is a pipe dream. Maybe you can’t commit to inerrancy and save the ship too. It’s very frustrating.”

Vines, on the other hand, is more sanguine. “Southern Baptists have great doctrinal unity,” he says, “which produces tremendous programs of missions and evangelism.” As president, “I desire to create an atmosphere or set a tone for reconciliation in the denomination. I hope to be able to indicate to our denomination that, whereas we may disagree on many levels, we can agree on Christian behavior towards one another.”

The potential of Vines’s success at his goal is strengthened by the fact that for appointments he can draw heavily from a pool of moderates who are inerrantists. In this way he can be true to his own theological convictions and simultaneously demonstrate that he wants to reach beyond the confines of the so-called Pressler-Patterson coalition.

Bill Leonard thinks, “If fundamentalists want to save the convention, they will begin to appoint people such as Winfred Moore [an Amarillo pastor, conservative on biblical authority but classified as a moderate] and Jackson. If they do that they might develop a new coalition.” Leonard fears such may not happen because conservatives have “made promises to people on their right.” Still, such mending is exactly what moderates like Jackson hope for. “Don’t give up on Dr. Vines,” he counseled his fellow Baptists in San Antonio. “Ask God to make him the greatest leader we’ve ever had, because that’s what we need.”

Bigness, Next To Godliness

Perceptive Southern Baptists see other profound challenges in their future. They see the convention increasingly concerned with celebrity, with an unbridled church growth that focuses single-mindedly on numbers, with a growing gap between the incomes of “super pastors” and their congregants (see p. 20), and with uncritical attitudes about national political entanglements that foster cultural captivity.

As the publisher of Will Campbell’s book summarizes the author’s concern, fundamentalists and moderates “prove themselves to have risen steadily up the steeples of power—so high that they have lost sight of the homeless people on the streets, lonely Vietnam veterans in the parks, Blacks and Orientals and Hispanics in mission chapels, and even the aging membership of the Women’s Missionary Union, who still meet faithfully in church basements while the male pastors and deacons concern themselves over eighteen holes of golf.” In other words, nothing may be so dangerous to this church as success.

John Thomason, a third-generation Southern Baptist and president of the Southern Baptist Alliance, speaks of seeing famous pastors followed by flocks of overeager disciples. “We’ve come to see bigness as next to godliness,” he believes. “The normative model in the SBC is now the superchurch. But for every 100 people who join those churches, there are thousands driven away from the faith by their style and tone. Yet we can’t see this because we are basking in success—in numbers.”

The plain-spoken Jackson agrees there is a danger of superpastors accruing too much power. “Get a roomful of Southern Baptist preachers together and you’ve got enough ego to blow Washington, D.C., off the map,” he cracks. He concurs with a “messenger” (a delegate to the convention) who, nominating the sole lay candidate for president this year, said the convention was by default “creating a College of Cardinals of our own,” leaving laypersons to watch the white smoke ascend from the midst of the magisterial clergy. That nominating messenger lamented that lay strength is the uniqueness of the convention, yet it has had only three lay presidents in its 143-year history. Comments Jackson: “The greatest thing that could have happened to us would be to have had a qualified layperson as president of the convention.”

Just As They Are

Bill Reedy

Church planter.

Bolingbrook, Illinois

Generations of Southern Baptists: Two; three in my wife’s family. I didn’t realize there was any other kind of Baptist!

Most memorable sermon from childhood:

“God’s Axe.” It was delivered during an area-wide “tent revival” with a traveling evangelist. There was a large tent, folding wooden chairs, sawdust on the ground.

Memorable summer camp experience:

Every Southern Baptist teenager who grew up in Oklahoma in the sixties spent a week at Falls Creek Baptist Assembly, located near Davis, Oklahoma. There were at least three weeks of camp with four or five thousand attending each week. The music, preaching, summer heat, and holding your girlfriend’s hand made the experience quite memorable.

Personal doctrinal struggle:

My struggle deals more with how to practice my beliefs and share my insights without being labeled a “liberal.” For instance, I believe in the authority of Scripture, but I am not a “literalist.” Many of my colleagues seem to equate the two.

Leonard, too, is concerned about what he calls the “clericalization” of the convention. He says there are churches splitting in the denomination because of authoritarian ministers, a style he thinks fundamentalism fosters.

In short, these and other Southern Baptists fear the cultural captivity of their denomination. That is, because Southern Baptists as a rule do not smoke, drink, or dance, they may believe they are free of undue cultural influence. Yet culture can influence in more subtle—and perhaps more destructive—ways. The style of “doing church” chosen by many conservative leaders may call for scrutiny and criticism.

Strength And Hope

Southern Baptists have been in an earnest fight among themselves for a decade now. All are tired of the battle, even those who thought it necessary to wage it. Yet the Southern Baptist spirit, overall, remains indomitable. The leaders we talked to refer to several strengths that give the convention real hope with which to face the challenges ahead.

Foremost is the continuing power of the SBC’s evangelism and missions. As Paige Patterson puts it, “We are still the most aggressively missionary and evangelistic of any of the mainline denominations.” (The SBC, he adds, has 3,800 career missionaries overseas.) Leonard finds cheer in the “deep and genuine” piety so pervasive in the denomination: “On a day-to-day basis, in local and regional areas, we do well at feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, and providing a witness to the gospel.” Bisagno even sees the possibility of denominational healing in a continuing, if intensified, commitment to missions. “If all you did was preach the gospel to the ends of the earth,” he says, “you wouldn’t have the problem of division.”

There are other strengths. Patterson mentions an emphasis on religious liberty and congregational autonomy as “a major contribution to the nation.” He thinks the six Southern Baptist seminaries—three of which are among the largest in the world—continue “to pour into America a strong emphasis on private education, which is now somewhat endangered in our country.” Finally, he doubts that many denominations have as many expert pulpiteers as the SBC.

Whatever his fears about clericalization, Jackson takes heart in the “rock-ribbed faith of the laypeople in our church.” Southern Baptists, to their advantage, continue to be “people of the pews” and “people of the Book.” Jackson remarks, “I think our people have enough knowledge of the Bible that they will not forever be fooled.”

Jerry Vines names similar strengths: “Our position as a Bible-believing denomination; our congregational form of government; and our inclination to work together on the basis of voluntary cooperation.”

Given the recognition by this variety of Southern Baptists of what is important to the convention, one suspects even the sardonic Will Campbell might find some room for optimism about the denomination. Moderates and conservatives alike, when asked to state what remains good and right about their denomination, point to the emphasis on the importance of local congregations and their liberty, a solid biblical base, and the centrality of the laity. Perhaps the moderates and the conservatives have failed to “care about where we Baptists came from.” But they haven’t forgotten it.