Harold’s parents came from Norway around the turn of the century. They ended up farming in eastern Montana, where Harold was born. His parents were pious, peasant Christians-Lutherans, to be sure. They were not overly impressed with the “enlightened” wealthy classes of Norway.

Harold grew up working hard. Witnessing his parents’ faith as they toiled to make a living in the harsh environs of the Montana highline, he embraced their faith with a full heart. Early in his adulthood, Harold stopped believing that God spoke Norwegian, but that’s also about where his acceptance of modern thought halted.

He married a woman of German Baptist origins, and they decided to be Baptists. Wheat farming never suited Harold, and the Depression took their farm, so the family moved to western Montana, where Harold and his wife ranched.

They raised cattle and kids, in no particular order-they lovingly cared for all of them. The cattle, who were practically pets, always took top money at auctions. And the kids, raised on blue skies and hard work, became successful adults.

The New World

But somewhere along the way, Harold’s kids didn’t pick up his faith. They were all married in churches. And they all made sure Harold’s grandchildren were baptized or dedicated, depending on the church they attended.

But their professional lives and the hectic pace and abundant possibilities of the fifties and sixties had separated all of Harold’s children and grandchildren from church involvement by the time the middle seventies rolled around. His children and grandchildren, all about the nicest people you could meet, formed the inner core of the “me generation.”

Although not all of them graduated from college, each of them ended up thoroughly pickled in modernity. Amid the din of their business and busyness, they still found time to wonder about the meaning of their lives, but only in terms of the self. “Fulfillment” of the self became the filter through which they processed their understanding of the world.

The difference between Harold’s generation and the following generations is starkly illustrated by Harold’s grandson Steve.

Steve and his family live in Seattle. Steve earned a law degree, but he tired of practicing law and went into business with a friend who describes himself as a “computer nerd.” Together they are developing and marketing software nationally. They aren’t making a fortune, yet.

Steve’s wife is a newspaper editor, and they have two grade-school kids whom they see most days. After expenses and savings, the family still has plenty left over for splendid vacations, for which they leave exhausted, and from which they return exhausted.

In quiet moments, Steve evaluates whether he is reaching his goals, which he largely is, and whether he is happy, which he largely is not.

He can’t pin down why he isn’t happy, since he is reaching his goals. He can’t seem to work hard enough or gain enough to feel sufficiently good about himself.

Often he has thought about moving his family and business out to Montana, where his grandfather Harold and his father and mother still live. In Montana, he thinks, he might find some peace of mind. But his wife and business partner enjoy living in Seattle; so he stays.

This doesn’t trouble Steve too greatly. He likes to dream about living in Montana, but he suspects it wouldn’t solve his problem.

Harold, who retained great physical energy into his eighties, eventually was struck with cancer. He gradually weakened, but never lost his warmth or deep faith. He finally died, full of years, with a Norwegian accent lacing his last words.

When the Old World Passes Away

Before he died, I visited Harold in the hospital, and we talked about his funeral service, about the hymns we would use and the nature of the message. I promised him I would talk about our hope in Christ and little about him, which pleases old Scandinavians.

Harold said he was grateful for the many times the Lord had pulled him through tough spots: “I don’t know how anyone can make it in this world without the good Lord’s help every step of the way.”

He also talked plainly about his death, without fear.

“I’ll be going soon,” he said, “but not until the Lord decides it’s time. When that time comes, I’ll go. There won’t be anything the doctors and nurses can do about it. And I’ll be ready.” He talked like this, with a smile sometimes, sometimes while spitting up clumps from his lungs. Watching Harold convinced me that learning to die well is one of life’s most important tasks.

Steve and his family came to Montana for Harold’s last couple of days. Steve and I had become friends over the years, so my being in the hospital room with the family was natural.

From Steve and the family came an enormous outpouring of esteem for Harold. There was the normal grief, of course, but esteem was the keynote. When we were alone, Steve told me story after story about his grandfather, a man he obviously admired.

Yet in those dying hours and after the funeral, I sensed something wrong. Looking into the eyes of the old man coughing up his lungs and those of the young man whose cardiovascular system is properly exercised thrice weekly, I couldn’t help but feel that the old man was alive and the young man dead. And I couldn’t help but think that the young man knew it.

Steve was divided. He switched back and forth between love-laden grief for the old man and a kind of diffidence. The old man glowed with hope; the young man basked, for the moment, in his grandfather’s peace. But then he looked within and couldn’t find anything inside himself that could relate to the old man’s beatific presence.

There was a dreadful admission that God was present, but by default, Steve couldn’t embrace him with faith.

The funeral went well, mainly because Harold’s life preached the sermon. But after the tears and consoling laughter of the wake, Steve left Montana in despair.

After Steve and his family returned to Seattle, I heard from Steve’s mother that they were having trouble. Steve had become confused and angry. He was losing interest in his job, and in his marriage.

Two Worlds Side by Side

Being in the hospital with Harold never depressed me, but watching Steve watch Harold took something out of me. Yet it put something in me, too.

Something of both Steve and Harold dwelt within me; they represent two different worlds I am stuck between. In that hospital room, I saw those two worlds come together, the old world of Harold critically interacting with the new world of Steve.

Steve’s world is preoccupied with the self. Yet, ironically, this preoccupation with the self produces the very lack of self-esteem that absorption with self is intended to produce. Harold’s secret was that he had spent his life not seeking esteem or glory for himself. His experience of esteem was effortless, but it was the weightiest kind.

Esteem is related to giving glory to whom glory is due. To give glory simply means to recognize weightiness and confess it. The human self was created by God to recognize and confess the weightiness of another, namely God. When it does, we participate in the glory of God and experience its benefits, which, among other things, include self-esteem. Only when we do what we were created to do-give glory to God-do we feel good about ourselves. Thus, self-esteem is a derived esteem.

Steve loved his grandfather and respected him as a businessman. But Steve thought his grandfather’s faith naive and stultifying, burdened with the notion of utter obedience to God. For Steve, the self was a calling to fulfill. So Steve decided early he would think and live more freely, entertaining experiences his grandfather denied himself.

While Steve became free from religion, he was not free in any other sense. He became addicted to work, physical exercise, video entertainment; he increasingly became attracted to pornography and to the “therapeutic” use of alcohol. In one sense, such activities are designed to lose the self. So, part of Steve was trying to fulfill his true self, and part was trying to lose the self he found discomforting.

His grandfather felt easy about himself; Steve hated himself. Steve had become addicted to fulfilling himself, but in the end, he began losing and destroying his sense of self.

The only power the self has is to give control to something else. As Paul put it, we can be slaves to sin or slaves to righteousness. But the self desperately tries to fulfill itself by gaining control of its environment. In its hunger for fulfillment, it will try anything.

Addiction is the self’s last-ditch effort to gain control over something. By giving itself utterly to an activity, however, it ends up losing the self.

Harold was untouched by addiction, but Steve is addicted to many things, and lives in an addicted society.

Ministry to Steve’s World

Harold and Steve are, of course, composites of many people I’ve encountered in ministry. The Harolds of this world are easier to minister to, but their lot is decreasing.

The Steves, on the other hand, continue to challenge me. They tend to balk at committing themselves to the covenant relationships the Scriptures call us to live in-in our families, in the church, and with God. The Steves are more committed to fulfilling the self, and, therefore, are in the process of losing the self, as well.

So, how can the church reach out to a generation intent on fulfilling and losing itself? Obviously, a complex problem offers no easy solutions, but here are some things I do.

Doing what we do best. Some churches, in an attempt to identify with Steves, recreate the world in which the Steves live. In these churches excitement is everything, and boring someone is a sin. The worship services and fellowship programs make people happy, but they function as an abyss for the self, working on the self like any other addiction.

When the Steves come to these churches, instead of being offered something different and meaningful, they are presented with more of what they already have: activity and distraction.

Seventeen years ago I took my first call as a youth worker at a large Presbyterian church in Southern California. I built my ministry on a simple observation: a church youth group never could be as much fun as Disneyland, the beach, or the back seat of a Chevy.

Instead, I decided we would accept kids for who they were, love them, and tell them about Jesus Christ. Of course, we went to the beach and Disneyland (they were on their own to provide the Chevys). But my first priority was to do the things we could do better than any other organization or activity they belonged to. That remains my priority today.

Glorifying God; healing ourselves. Sometimes we naively assume that if people out there only knew what a great time we Christians have, they would long to join us. From this perspective, the church’s main problem is lack of proper promotion.

But this ignores the depth of the challenge: the problems of the generation we want to evangelize are our problems, as well. As the Harolds leave us, we are left with just us, and a world dominated by Steve’s values.

An alcoholic can best help his family by getting well. Likewise, the church best helps its community by working at getting well itself. Only then can it become a place where others can come and get well, where addictions we all struggle with are dealt with openly and empathetically.

The place to begin this process is, of course, worship, where the self is encouraged to turn outward by obeying and glorifying God. Among the many demands of ministry, then, worship remains my highest priority; it is the most effective way of challenging Steves and healing self-absorption.

Among pastors, releasing control. Naturally, the surrender of the self to obey and glorify God is the very thing the self is least apt to do. The self doesn’t want to lose control.

As ministers, we feel out of control and constantly attempt to regain it in our own lives and ministries. Sometimes we attempt to gain control over people, in the name of the gospel, by building elaborate programs. We want to control the religious environment and so gain self-esteem for ourselves through ministry. Certainly motives-good and bad, of the Spirit and of the flesh-mix and mesh to become an inextricable web in ministry. But many times we’re just scared Steves grasping for control.

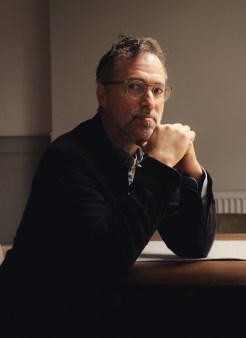

To deal with my temptation to this addiction, I keep in touch regularly with a few choice pastor friends to discuss our yearning to control, our self-esteem, and our resulting addictions, including church work. Some live in different parts of the country, but I can phone them anytime. They listen knowingly, and they understand me well enough to tell me when I feed them baloney.

Others I meet with regularly. In Montana, with long distances separating us, we often have to drive four or more hours to meet. The advantage of this situation is that we have little choice but to make a day of it, spend the night, and leave the next morning.

One pastor friend and I meet several times a year. We both drive four hours to a centrally located Christian camp and spend about twenty-two hours together. Our agenda is simple. Each of us tries to answer this question: What has become clear to me since we last met?

To put it another way, we are practicing spiritual direction for one another. We discuss personal issues and mundane ones, like which word processor software we are using. We discuss our struggles in pastoral ministry and try to understand the emotions that ministry produces. We offer one another solutions to various ministry problems. And we talk about prayer a lot.

We almost always find that the grace of God is impinging, one way or another, on our lives. Often we see for one another where God is working, where alone, we couldn’t.

This time is always refreshing, an experience of the eschaton, when I believe we will have unstructured time for experiencing life as it comes to us.

In addition, our time together models for us how we want to work with our people.

Releasing control through prayer. Prayer is what led me to see Steve and myself for what we are. So much for the idea that prayer is calming! Furthermore, I’ve learned that prayer is undoubtedly our most important ally in ministry to the Steves.

Prayer is the means by which God can deliver us precisely because it is an activity over which we have little control. Prayer, because it seeks God and his control, subverts our own drive to control. In addition, we can reach the inward-directed, control-oriented self of others only through ministries that are undergirded with the activity of prayer.

So, often in the middle of my workday, I push away from my desk, leave the church building, and go to a place where I can walk and pray. Presently, I stroll through the woods, wilderness, and river bottoms of western Montana. But I’ve covered the same business pacing through city streets and peach orchards and suburban neighborhoods. During my walks I ruminate and go over people’s needs with God. Sometimes it goes smoothly and sometimes it’s argumentative, but always I am reminded that God is in charge of his people’s lives-not I.

Treating people seriously. People like Steve live with stored-up guilt. We can hardly overestimate how much guilt people are living with. What they need to hear ultimately is the forgiveness of God and the gospel of new life in Christ through repentance. But before that, the Steves of this world need to have their sin taken seriously.

In our preaching, we insult people when we pretend they never have seriously rebelled against God. The self’s terrible ability to sin demonstrates that we have the remarkable and unique gift of human freedom. Paradoxically, then, acknowledging people’s sin acknowledges their uniqueness and worth.

In addition, sin is a misuse of our freedom, but only because in sinning we take seriously (too seriously) our place and position in the universe. So, when we acknowledge people’s sin, we acknowledge the passionate seriousness with which they conduct their lives.

I’m not talking about whipping people for their sins. But in my experience, people take the good news of God’s forgiveness seriously only when first their sin has been taken seriously. When the Steves in our pews sense that we don’t understand the depth of their predicament before God, they can never hear the gospel.

Naturally, we pastors first must understand the depth of our predicament before God, and we must experience the forgiveness of God in our lives before we can preach it credibly to others.

Life Is Learning to Die Well

At the awkward moment of death, Steve didn’t evaluate Harold’s success the same way Harold did. When asked why he could face death so confidently, Harold’s reasons were simple: he trusted in God, and God was faithful. It sounds like a page out of the book of Proverbs or a recitation of Psalm 1.

Steve, however, mentioned all of the wonderful qualities of his grandfather-hardworking, sacrificing, strong, honest-except his faith. Harold talked little about these qualities and much about God.

As I witnessed Harold’s last days, an embarrassingly revealing light was cast on my life. But I also discovered that in watching someone like Harold die, I was given a model on how to live and minister.

Copyright © 1990 by the author or Christianity Today/Leadership Journal. Click here for reprint information on Leadership Journal.