As Washington politicians and commentators scrutinize Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas, abortion and church/state relations have emerged as key issues surrounding Bush’s appointee to the high court. And while Thomas’s history on the bench leaves many questions unanswered, most Court observers agree he would probably serve to solidify the judicial trend that has already emerged on the Court.

Thomas has never decided a case involving abortion or publicly stated his views on Roe v. Wade. Prolife activists say even without Thomas, six members of the Court are open to arguments to overturn Roe. The National Right to Life Committee (NRLC) has not taken a position on Thomas, but expressed satisfaction that he has pledged to “faithfully interpret the Constitution and not legislate from the bench.”

Another clue to Thomas’s views may be found in his participation in a 22-member White House working group on the family, headed by former Reagan aide Gary Bauer, now president of the Family Research Council (FRC). In 1986, the working group released its report, which among other things criticized the Supreme Court for striking down “state attempts to protect the life of children in utero, [and] to protect paternal interest in the life of the child before birth,” citing the Roe decision.

The National Abortion Rights Action League, the National Organization for Women, and other abortion advocates are opposing Thomas’s nomination based on the fact that he once praised an American Spectator article that called abortion on demand “a spurious right born exclusively of judicial supremacy.”

Church/State Cases

Thomas has also never ruled on a church/state case or articulated his philosophy on the separation of church and state. This has been a controversial area for the Supreme Court in recent years, particularly in light of its 1990 Oregon v. Smith “peyote” decision, which said states need not show a compelling interest when subordinating an individual’s religious rights to the state’s legislative purposes (CT, July 16, 1990, p. 48). Retiring Justice Thurgood Marshall, always a strong supporter of religious rights, voted in the minority on the Smith decision.

According to Forest Montgomery, general counsel for the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE), a majority still exists on the Court that is willing to restrict individual religious rights. “So whichever side Clarence Thomas comes down, it wouldn’t make a difference on that issue,” he said.

One area in which Thomas could make a difference is church/state cases involving questions of the establishment of religion—for example, prayer at a public-school graduation ceremony. Americans United for Separation of Church and State, a group that opposes government accommodation of religion, has urged the Senate Judiciary Committee to “thoroughly examine” Thomas’s church/state views before confirming him.

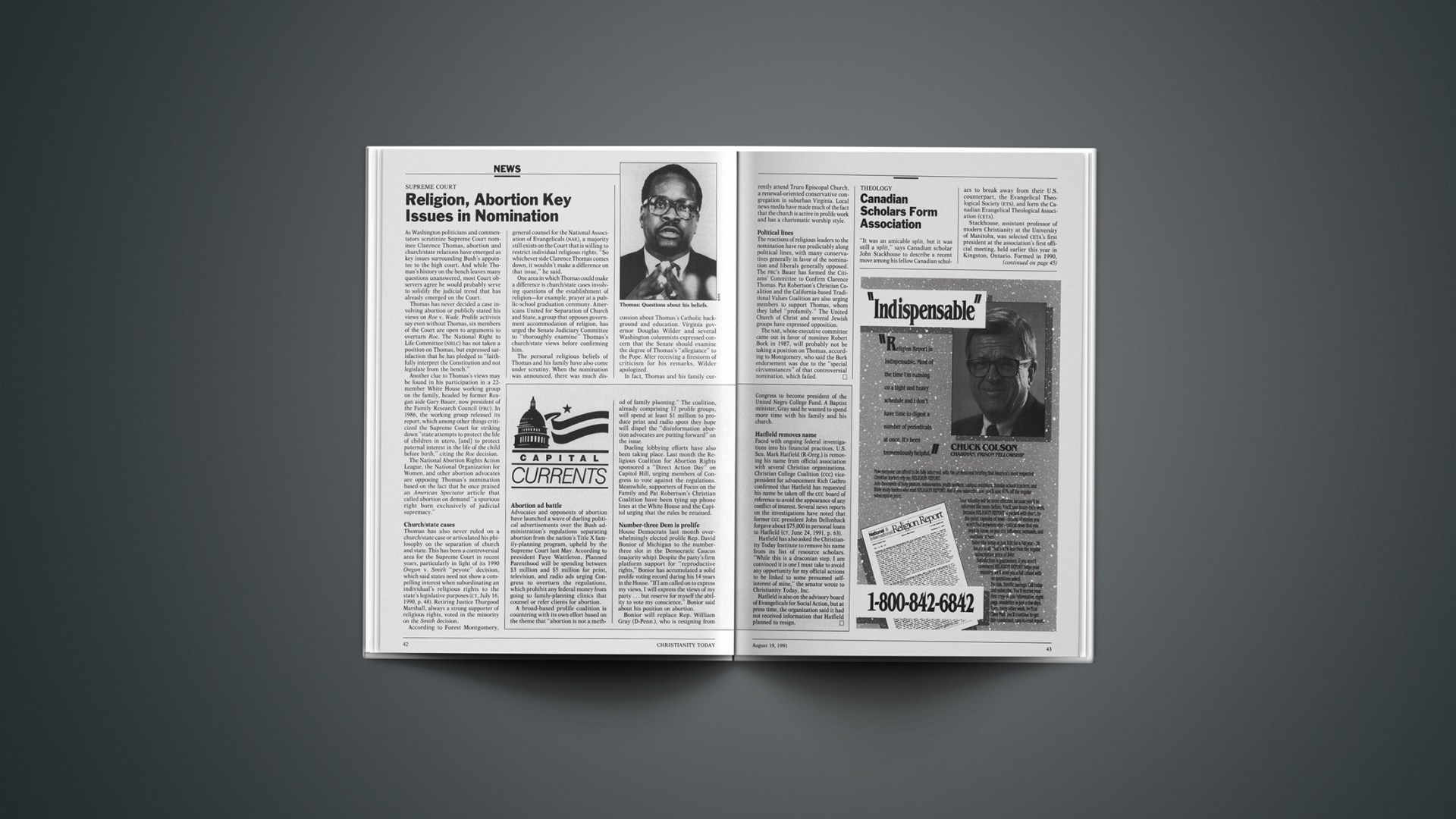

The personal religious beliefs of Thomas and his family have also come under scrutiny. When the nomination was announced, there was much discussion about Thomas’s Catholic background and education. Virginia governor Douglas Wilder and several Washington columnists expressed concern that the Senate should examine the degree of Thomas’s “allegiance” to the Pope. After receiving a firestorm of criticism for his remarks, Wilder apologized.

In fact, Thomas and his family currently attend Truro Episcopal Church, a renewal-oriented conservative congregation in suburban Virginia. Local news media have made much of the fact that the church is active in prolife work and has a charismatic worship style.

Political Lines

The reactions of religious leaders to the nomination have run predictably along political lines, with many conservatives generally in favor of the nomination and liberals generally opposed. The FRC’s Bauer has formed the Citizens’ Committee to Confirm Clarence Thomas. Pat Robertson’s Christian Coalition and the California-based Traditional Values Coalition are also urging members to support Thomas, whom they label “profamily.” The United Church of Christ and several Jewish groups have expressed opposition.

The NAE, whose executive committee came out in favor of nominee Robert Bork in 1987, will probably not be taking a position on Thomas, according to Montgomery, who said the Bork endorsement was due to the “special circumstances” of that controversial nomination, which failed.