In this series

In 1942, Lutheran pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer sent a Christmas gift to his family and his friends who were involved in a plot to kill Hitler. It was an essay, titled “After Ten Years.” In it, Bonhoeffer reminded his co-conspirators of the ideals for which they were willing to give their lives. In his words: “We have for once learned to see the great events of world history from below, from the perspective of the outcast, the suspects, the maltreated, the powerless, the oppressed, the reviled—in short, from the perspective of those who suffer.”

As he sifted through the various reasons why they had to kill Hitler and bring down the Nazi government, Bonhoeffer spoke to them of the example of Jesus Christ. Jesus had willingly risked his life defending the poor and outcasts of his society—even at the cost of a violent death.

By the time of his arrest, Bonhoeffer’s life had become an ever-twisting journey in which he had been moved to action by that “view from below.” His life took him from a comfortable teaching post at the university to the isolated leadership of a minority opposition within his church and against his government. He moved from the safety of a refuge abroad to the dangerous life of a conspirator. He descended from the privileges of clergy and the respect accorded a noble family, to his harsh imprisonment and eventual death as a traitor to his country.

Steely Determination

Few people would have predicted that the young Bonhoeffer would end up as a political conspirator. Born in Breslau in 1906, Dietrich was his family’s fourth son and sixth child (his twin sister, Sabine, was born moments later). His mother, Paula von Hase, was daughter of the preacher at the court of Kaiser Wilhelm II. Dietrich’s father, Karl Bonhoeffer, was a famous doctor of psychiatry and professor at the university.

As a lad of 14, Dietrich surprised his family by declaring he wanted nothing more than to be a minister-theologian in the church. That announcement provoked mild consternation among his brothers. One was destined to be a physicist, the other a lawyer; both were achievers for whom service in the church seemed a sinecure for the petty bourgeois. His father felt the same way but kept silent, preferring to allow his son freedom to make his own mistakes. When his family criticized the church as self-serving and cowardly, a flash of Dietrich’s steely determination came out: “In that case, I’ll reform it!”

A “Theological Miracle”

Following a family custom, young Dietrich studied at Tübingen University for one year before moving on to the University of Berlin, where the family resided. At the university, he came under the influence of distinguished church historian Adolf von Harnack and Luther scholar Karl Holl.

Von Harnack regarded Bonhoeffer as a potentially great church historian able one day to step onto his own podium.

To von Harnack’s dismay, Bonhoeffer steered his scholastic energies to dogmatics instead. His main interests lay in the allied fields of Christology and church. Bonhoeffer’s dissertation, The Communion of Saints, was completed in 1927, when he was only 21. Karl Barth hailed it as a “theological miracle.”

In this dissertation Bonhoeffer declares in a ringing phrase that the church is “Christ existing as community.” The church for him is neither an ideal society with no need of reform, nor a gathering of the gifted elite. Rather, it is as much a communion of sinners capable of being untrue to the gospel, as it is a communion of saints for whom serving one another should be a joy.

Grim Encounter with Poverty

Not yet at the minimum age for ordination, and in need of practical experience, Bonhoeffer interrupted his academic career. He accepted an appointment as assistant pastor in a Barcelona parish that tended to the spiritual needs of the German business community.

His months in Spain (1928–29) coincided with the initial shock waves of the Great Depression. Hence, parish life in Barcelona gave Bonhoeffer his first grim encounter with poverty. He helped organize a program his parish extended to the unemployed. In desperation, he even begged money from his family for this purpose. In a memorable sermon he reminded his people that “God wanders among us in human form, speaking to us in those who cross our paths, be they stranger, beggar, sick, or even in those nearest to us in everyday life, becoming Christ’s demand on our faith in him.”

Back in Germany, Bonhoeffer turned his attention to his “second dissertation”—required to obtain an appointment to the university faculty. Published as a book in 1931, Act and Being outwardly appears to be a rapid tour of philosophies and theologies of revelation. If revelation is “act,” then God’s eternal Word interrupts a person’s life in a direct way, intervening often when least expected. If revelation is “being,” then it is Christ’s continued presence in the church. Throughout the intersecting analyses of this book, we also detect Bonhoeffer’s deep struggle between the lure of academe’s comfortable status, and the unsettling call of Christ to be a genuine Christian.

First Visit to America

Having secured his appointment to the university faculty, Bonhoeffer now decided to accept a Sloane Fellowship. This offered him an additional year of studies at Union Theological Seminary in New York. Later he would describe this academic year of 1930–31 as “a great liberation.”

At first, Bonhoeffer looked harshly on Union Theological Seminary, judging it to be so permeated with liberal humanism that it had lost its theological moorings. Yet courses with Reinhold Niebuhr and long conversations with his closest American friend, Paul Lehmann, stirred sensitivity to social problems.

Bonhoeffer’s friendships at Union deeply influenced him. They fueled his growing passion for the concerns of the Sermon on the Mount. Through a black student from Alabama, Reverend Frank Fisher, Bonhoeffer experienced firsthand the oppressive racism endured by the black community of Harlem. Admiring their life-affirming church services, he took recordings of black spirituals back to Germany to play for his students and seminarians. He spoke to his students often about racial injustice in America, predicting that racism would become “one of the most critical future problems for the white church.”

Another friend, the French pacifist Jean Lasserre, moved Bonhoeffer to transcend his natural attachment to Germany in order to make a deeper commitment to the cause of world peace. Bonhoeffer became devoted to non-violent resistance to evil, and later he strongly advocated peace at ecumenical gatherings. For Bonhoeffer, war overtly denied the gospel; in it, Christians killed one another for trumped-up ideals that only masked more sinister political aims.

People noticed the changes in Bonhoeffer’s outlook on his return to the University of Berlin. His students described him as unlike his more stuffy, aloof colleagues. Trying to explain what had happened to him, Bonhoeffer said simply that he had become a Christian. As he put it, he was for the first time in his life “on the right track,” adding, “I know that inwardly I shall be really clear and honest only when I have begun to take seriously the Sermon on the Mount.”

Electrifying University Lecturer

Returning from America, Bonhoeffer paused at Bonn University, where he finally met theologian Karl Barth. Barth’s writings had electrified the theological world and had captivated Bonhoeffer during his student days in Berlin. Now the two became good friends. Barth appreciated Bonhoeffer’s incisive warnings about organized religion’s cozy accommodation of political ideologies. Bonhoeffer began to use Barth as a sounding board, trusting Barth’s mature assessments of how to counteract the church’s compromises with Nazism.

The youngest teacher on the faculty, Bonhoeffer became noticed for his way of probing to the heart of a question and setting issues in their present-day relevance. One student wrote that under Bonhoeffer’s guidance “every sentence went home; here was a concern for what troubled me, and indeed all of us young people, what we asked and wanted to know.” Yet Bonhoeffer’s teaching career was shadowed by Hitler’s ascendancy to power. Students attracted to Nazism avoided him.

Some of Bonhoeffer’s university courses during this period have since been published as books. In The Nature of the Church, Bonhoeffer observed that the church had gone adrift; it had too often sought the comfort of the privileged. The church, he told his students, had to confess faith in Jesus with unaccustomed courage and to reject without hesitation all secular idolatries.

In his lectures on Christology, published as Christ the Center, Bonhoeffer urged his students to answer disturbing questions: Who is Jesus in the world of 1933? Where is he to be found? For him, the Christ of 1933 was the persecuted Jew and the imprisoned dissenter in the church struggle.

During the university years, Bonhoeffer also found time to teach a confirmation class in a slum section of Berlin. To be more involved in the confirmands’ lives, he moved into their neighborhood, visited their families, and invited them to spend weekends at a rented mountain cottage. After the war, one of these students remarked that the “class was hardly ever restless.”

Growing Church Struggle

During this period, many Christians within Germany had adopted Hitler’s National Socialism as part of their creed. Known as “German Christians,” their spokesman, Hermann Grüner, made it clear what they stood for:

“The time is fulfilled for the German people in Hitler. It is because of Hitler that Christ, God the helper and redeemer, has become effective among us. Therefore National Socialism is positive Christianity in action.… Hitler is the way of the Spirit and the will of God for the German people to enter the Church of Christ.”

Ordained on November 15, 1931, Bonhoeffer, with his group of “Young Reformers,” attempted to persuade delegates to church synods not to vote for pro-Hitler candidates. In a memorable sermon just before churchwide elections in July 1933, Bonhoeffer pleaded: “Church, remain a church! Confess, confess, confess!” Despite Bonhoeffer’s efforts, the German Christians elected as National Bishop a Nazi sympathizer, Ludwig Müller. In a letter to his grandmother that August, Bonhoeffer stated frankly, “The conflict is really Germanism or Christianity, and the sooner the conflict comes out in the open, the better.”

By September 1933, the conflict was out in the open. In the “Brown Synod” that month (so called because many of the clergy wore brown Nazi uniforms and gave the Nazi salute), the church adopted the “Aryan Clause,” which denied the pulpit to ordained ministers of Jewish blood. Bonhoeffer’s closest friend, Franz Hildebrandt, was affected by the legislation (along with countless others). This Aryan Clause would split Germany’s Protestant church.

Outspoken Defense of the Jews

Bonhoeffer’s first public reaction to the anti-Jewish legislation had come early. In April 1933 he talked to a group of pastors on “The Church and the Jewish Question.” In his address, he urged the churches to first, boldly challenge the government to justify such blatantly immoral laws. Second, he demanded that the church come to the aid of victims—baptized or not. Finally, he declared that the church should “jam the spokes of the wheel” of state should the persecution of Jews continue. Many of the gathered clergy left in a huff, convinced they had heard sedition.

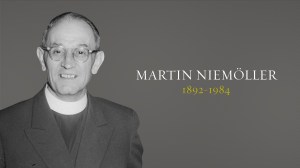

Shortly after the Brown Synod, Bonhoeffer and a World War I hero, Pastor Martin Niemöller, formed the “Pastors’ Emergency League.” They pledged to fight for repeal of the Aryan Clause, and by late September, they had obtained 2,000 signatures. But to Bonhoeffer’s disappointment, the church’s bishops again remained silent.

At the Barmen Synod of May 29–31, 1934, however, the new “Confessing Church” (those pastors who opposed the Aryan Clause and other Nazi policies) affirmed the now-famous Barmen Confession of Faith. Drawn up in large part by Karl Barth, its association of Hitlerism with idolatry made many of the signers marked men with the Gestapo: “We repudiate the false teaching that there are areas of our life in which we belong not to Jesus Christ but to other lords.… ”

Abandoning a Promising Career

Because the German Christians were now entrenched in church leadership positions, Bonhoeffer was rejected for a pastorate. The comments against him pointed out his radical and intemperate opposition to government policies. And he was considered too linked with his Jewish-Christian friend, Franz Hildebrandt. The creeping Nazification of the churches left Bonhoeffer feeling isolated and unable to muster a fearless opposition to Hitler among the clergy.

In his teaching post, he felt the university had inexcusably yielded to the popular mood that hailed Hitler as a political savior. He was disturbed, too, by the universities’ lack of protest at the disenfranchisement of Jewish professors. These frustrations made it easier for Bonhoeffer to decide to leave Germany. In the fall of 1933 he assumed the pastorate of two German-speaking parishes in London.

For this move, Bonhoeffer received a stinging rebuke from Karl Barth, who thought he was fleeing the scene when he was most needed. Barth accused Bonhoeffer of depriving the church struggle of his “splendid theological armory” and “upright German figure.”

Yet Bonhoeffer was not abandoning the fight against Nazism. From London, he intended to bring outside pressure on the German Reich Church. In a letter to the head of the Ecclesiastical Foreign Ministry, Bonhoeffer refused to abstain from criticism of the German government.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer and other delegates attended an ecumenical conference in Fanø, Denmark, in 1934. At the conference, Bonhoeffer preached a stirring sermon to Christian leaders from more than 15 nations. “The world is choked with weapons,” he said, “and dreadful is the distrust which looks out of every human being’s eyes. The trumpets of war may blow tomorrow.” In such a time, he urged Christians to speak out against war and dare the “great venture” of peace.

Rallying World Church Support

It was at the ecumenical level that Bonhoeffer hoped more effectively to continue the church struggle. Bonhoeffer had been appointed international youth secretary for the World Alliance for Promoting International Friendship through the Churches (a forerunner of the World Council of Churches). In this role, he rallied the international churches to take a stronger anti-Nazi stand, to support the Confessing Church, and to oust the Reich Church from the ecumenical movement.

His activities led to a lasting friendship with English Bishop George Bell. Bell was president of the Universal Christian Council for Life and Work, which worked closely with the World Alliance. He endorsed Bonhoeffer’s plea that the Confessing Church be recognized as sole representative of the Protestant church of Germany.

Bonhoeffer’s efforts reached a climax at the 1934 conference held in Fanø, Denmark. Bonhoeffer’s Ecumenical Youth Commission astounded the delegates by its refusal to couch resolutions in polite diplomatic language. Further, Bonhoeffer wanted the churches to declare as unchristian any church that had become a mere uncritical adjunct of political policies. All delegates knew the German Reich Church was the target of these resolutions.

Bonhoeffer’s most lasting contribution to this conference, however, was an unforgettable morning sermon on peace, entitled “The Church and the Peoples of the World.” His student Otto Dudzus reported that Bonhoeffer’s words left the delegates “breathless with tension.” How could the churches even justify their existence, he asked, if they did not take measures to halt the steady march toward another war? He demanded that the ecumenical council speak out “so that the world, though it gnash its teeth, will have to hear, so that the peoples will rejoice because the church of Christ in the name of Christ has taken the weapons from the hands of their sons, forbidden war, proclaimed the peace of Christ against the raging world.” One sentence of that sermon remained forever emblazoned in the memories of Bonhoeffer’s students: “Peace must be dared; it is the great venture!” Even Dudzus remarked that “Bonhoeffer had charged so far ahead that the conference could not follow him.”

Brave New Seminary

In 1935, leaders of the Confessing Church asked Bonhoeffer to direct an illegal seminary near the Baltic Sea. For the Confessing Church, establishing its own seminaries was a bold move. They would simply bypass the typical training of candidates at universities tainted by Nazism. With their own seminaries, they could ignore the requirements that candidates prove their pure Aryan blood and loyalty to Nazism as conditions for ordination. These seminaries would be supported not by stipends from the government but by freewill offerings.

The young candidates, who gathered first at Zingst on the Baltic Sea and later at an abandoned private school in Finkenwalde, remembered the seminary as an oasis of freedom and peace. Bonhoeffer structured the day around common prayer, meditation, biblical readings and reflection, fraternal service, and his own lectures. Each day was lightened by recreation, including singing of the black spirituals Bonhoeffer had brought from America.

The highlight of their training, however, was Bonhoeffer’s lectures on discipleship. These gave rise to the best known of his books, The Cost of Discipleship. In it Bonhoeffer indicted Christians for pursuing “cheap grace,” which guaranteed a bargain-basement salvation but made no real demands on people, thus poisoning “the life of following Christ.” Bonhoeffer challenges readers to follow Christ to the cross, to accept the “costly grace” of a faith that lives in solidarity with the victims of heartless societies.

The Gestapo closed the seminary in October 1937. Bonhoeffer then tried to conduct a secret “seminary on the run.” This proved unsuccessful. The spirit of Finkenwalde has survived, however, in Life Together. Published in 1939, the book records the seminarians’ “experiment in community.” The church, Bonhoeffer believed, needed to promote a genuine sense of Christian community. Without this, it could not effectively witness against the nationalist ideology to which Germany had succumbed. A church congregation was not to be closed in on itself, but be a vortex of renewal for the spiritually drained and a refuge for the persecuted. Through prayer and caring service the church could become again “Christ existing as community.”

The Church’s Failure of Nerve

The years 1937 to 1939 were particularly problematic for Bonhoeffer and his role in the church struggle. The Confessing Church’s leaders seemed to lack fortitude on the question of taking the civil oath to Hitler. Hitler offered Confessing Church ministers legitimacy in return for their quiet support of his expansionist plans, including the annexation of Austria. Peace, respectability, and patriotism were the bait. Bonhoeffer wanted the bishops to defend the right of pastors to refuse taking the oath of allegiance to Adolf Hitler.

Bonhoeffer was stymied, too, in his efforts to stir up in the church a more strenuous opposition to the cruel persecution of the Jewish people. To him, church synods (assemblies) looked out for their own interests. They lacked heart for the more urgent issue: how to counteract the abuse and denial of civil rights within Germany. He decried their lack of sensitivity to the plight of pastors imprisoned for their dissent.

Whether the church leaders spoke up for the Jews now became Bonhoeffer’s measure of the success or failure of any synod. “Where is Abel your brother?” he would ask. Bonhoeffer’s essays and lectures of this period exude his bitterness over the bishops’ failure of nerve. He would frequently quote Proverbs 31:8, “Who will speak up for those who are voiceless?” to explain why he had to be the voice defending the Jews in Nazi Germany.

In June 1938 The Sixth Confessing Church Synod met to resolve the church’s latest crisis. Dr. Friedrich Werner, state commissar for the Prussian Church, had threatened to expel any pastor refusing to take the civil oath of loyalty as a “birthday gift” to Hitler. Instead of standing up for freedom of the church, the synod shuffled the burden of decision to the individual pastors. This played into the hands of the Gestapo, who could then easily identify the disloyal few who dared to refuse. Infuriated at the bishops, Bonhoeffer demanded, “Will the Confessing Church ever learn that majority decision in matters of conscience kills the spirit?”

Mistaken Trip to America

By the autumn of 1938 Bonhoeffer felt he was a man without a church. He could not influence the Confessing Church to take a courageous stand against a civil government he regarded as inherently evil. On the ecumenical front, he had been unable to persuade the World Alliance of Churches to unseat the German Reich delegation at their conferences. In February 1937, he resigned as youth secretary in protest.

On “Crystal Night” (Kristallnacht), November 9, 1938, the full frenzy of Nazi anti-Semitism was unleashed on Jewish citizens. The police watched passively as German hordes broke windows of houses and stores, burned synagogues, and brutalized Jews. Bonhoeffer was away from Berlin on that night, but he quickly raced to the scene. He discredited attempts to attribute this violence to God’s so-called curse of the Jews because of the death of Christ. In his Bible he underlined Psalm 74:8—“They say to themselves: let us plunder them! They burn all the houses of God in the land”—and marked it with the date of Crystal Night.

Bonhoeffer felt keen disappointment over the church’s dishonorable silence following that mayhem. This was one of the factors that led him to contemplate a second trip to America. He wanted to rethink his commitment to the Confessing Church, then the focal point of his opposition to Hitler.

Another reason for leaving Germany was the imminent call to arms of his age group. Bonhoeffer realized that his refusal to be inducted into the army would bring Nazi wrath upon his closest colleagues in the Confessing Church. Also, Bonhoeffer had entered closer contact with his brother-in-law, Hans von Dohnanyi. Dohnanyi, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, and Colonel Hans Oster (all in the military intelligence unit, or Abwehr) were preparing a military-led coup d’état. Bonhoeffer feared being an unwitting cause of the Gestapo’s stumbling on to their plans.

For all of these reasons, Bonhoeffer explored the possibility of leaving Germany, this time via a lecture tour in the United States for the summer of 1939. He intended to stay a year at most. His closest American friend, Paul Lehmann, and his former teacher, Reinhold Niebuhr, were eager to rescue Bonhoeffer from the fate of dissenters in Nazi Germany. Thus, they arranged for the tour with the unspoken intention that he would remain in America once the impending war began. Bonhoeffer embarked for the United States on June 2, 1939.

The peace of his journey was disturbed, however, by the thought of the persecution that dissenting pastors were facing. The Godesberg Declaration of April 4, 1939, had enjoined on all pastors the duty to devote themselves fully to “the Führer’s national political constructive work.” It was becoming even more dangerous to be numbered among the enemies of the Third Reich. Bonhoeffer’s diary for that period is filled with expressions of anxiety. Why had he come to America when he was needed by the Christians of Germany?

Bonhoeffer soon made up his mind to return. He departed on July 8, 1939, a mere month after his arrival. “I have made a mistake in coming to America,” he wrote to Reinhold Niebuhr. “I must live through this difficult period of our national history with the Christian people of Germany. I will have no right to participate in the reconstruction of Christian life in Germany after the war if I do not share the trials of this time with my people.”

Secret Courier Activities

On his return home, Bonhoeffer was forbidden to teach, to preach, or to publish without submitting copy for prior approval. He was also ordered to report regularly to the police.

The freedom to continue his writing came unexpectedly through his being recruited for the conspiracy. Hans von Dohnanyi and Colonel Hans Oster, leading figures in German military intelligence, arranged to have him listed as indispensable for their espionage activities. This exempted Bonhoeffer from the draft and, because he was assigned to the Munich office, removed him from Gestapo surveillance in Berlin.

His ostensible mission was to scout intelligence information through his “pastoral visits” and ecumenical contacts. Under this cover, however, Bonhoeffer was involved in secret courier activities. His principal mission was to seek terms of surrender from the Allies, should the plot against Hitler succeed. The highpoint of these negotiations came at a secret rendezvous with Bishop Bell in Sigtuna, Sweden in May 1942. Bonhoeffer convinced Bell that the conspirators could be trusted to overthrow the Nazi government, restore democracy in Germany, and make war reparations. Bell took the information to British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, but Allied response to Germany had already hardened into “Unconditional Surrender!”

When not dallying in the Munich office, Bonhoeffer made his headquarters in a nearby Benedictine monastery. There he continued writing what he once declared to be his main life’s work, Ethics. Posthumously reconstructed by Eberhard Bethge, the book is hardly a completed ethic. It is, rather, a collection of at least four fragmentary approaches to the construction of a Christian ethic in the midst of Germany’s national crises. In it, Bonhoeffer upbraided the church for not having “raised its voice on behalf of the victims and … found ways to hasten to their aid.” In a stinging phrase he declared the church “guilty of the deaths of the weakest and most defenseless brothers and sisters of Jesus Christ.”

Letters and Papers from Prison

While working for the Abwehr, Bonhoeffer also became involved in “Operation 7,” a daring plan to smuggle Jews out of Germany. This attracted the Gestapo’s suspicions. On April 5, 1943—after the conspiracy had led two failed attempts on Hitler’s life—Bonhoeffer was arrested and incarcerated at Tegel Military Prison in Berlin. At first the Nazis had only vague charges against him: his evading of the military draft, his role in “Operation 7,” and his prior disloyalties.

While in prison, Bonhoeffer wrote inspiring letters and poems that are now regarded as a Christian classic. After the posthumous publication of these Letters and Papers from Prison (by Eberhard Bethge), people around the globe began to appreciate Bonhoeffer’s creative, relentless probing into the meaning of Christian faith. In them, Bonhoeffer is harsh on religion for short-circuiting genuine faith. Meaningless religious structures and abstract theological language were a vapid answer to the cry of people lost in the chaos and killings of the battlefields and death camps.

In these letters, too, Bonhoeffer raised disturbing questions that would rattle the nerves of church leaders. In the letter of April 30, 1944, he confides that “what is bothering me incessantly is the question of what Christianity really is, or indeed who Christ really is, for us today.”

In responding to that question, Bonhoeffer observed that the church, anxious to preserve its clerical privileges and survive the war years with its status intact, had offered only a self-serving religious haven from personal responsibility. It had failed to exercise any moral credibility for a “world come of age.” The church had to shed those “religious trappings” so often mistaken for authentic faith. For Bonhoeffer, if Jesus is “the man for others,” then the church can be the church only when it exists to be of courageous service to people.

Bonhoeffer also wrote letters to his fiancée, Maria von Wedemeyer. He had fallen in love with Maria in 1942, during stays with her family between his Abwehr journeys. He had been charmed by her beauty, personal verve, and spirit of independence. Her family initially objected to their engagement because of their youth—she was 18, and he was 37. He was also involved in secret actions that could prove dangerous to her. But after his imprisonment, they publicly announced their betrothal as a display of support for him. Maria’s visits became Bonhoeffer’s main sustenance during the grim early days of his imprisonment.

One letter to Maria speaks of their love as “a sign of God’s grace and kindness, which calls us to faith.” Bonhoeffer adds, “and I do not mean faith which flees the world, but the one that endures the world and which loves and remains true to the world in spite of all the suffering which it contains for us. Our marriage shall be a yes to God’s earth.… I fear that Christians who stand with only one leg upon earth also stand with only one leg in heaven.”

Death Camp at Flossenburg

On July 20, 1944, the “officers’ plot” to assassinate Hitler failed. In the dragnet that ensued, the Gestapo’s investigations closed in on the main conspirators, including Bonhoeffer. He was transferred to the Gestapo prison in Berlin in October 1944. Maria and Dietrich were completely separated from each other. In February 1945, Dietrich was shifted to the concentration camp at Buchenwald. Amidst the chaos of the Allies’ final assault, Maria traveled to all the camps between Berlin and Munich, often by foot, in a futile attempt to see him again.

What we know of those last days is gleaned from the book The Venlo Incident, written by a fellow prisoner, British intelligence officer Payne Best. Bonhoeffer and Best were among the “important prisoners” taken to Buchenwald. Best later wrote of Bonhoeffer: “He was one of the very few men I have ever met to whom his God was real and ever close to him.… ”

On April 3, Bonhoeffer and others were loaded into a prison van and taken to the extermination camp at Flossenbürg. In transfers of prisoners like this, death sentences had already been decreed in Berlin. The SS carried out the formalities of a court martial, executed these enemies of the Third Reich, and disposed of the bodies.

On April 8, they reached the tiny Bavarian village of Schönberg, where the prisoners were herded into a small schoolhouse being used as a temporary lockup. It was Low Sunday, and several prisoners prevailed on Bonhoeffer to lead them in a prayer service. He did so, offering a meditation on Isaiah’s words, “With his wounds we are healed.” In his book Best recalled that moment: “He reached the hearts of all, finding just the right words to express the spirit of our imprisonment, and the thoughts and resolutions which it had brought. ”

Their quiet was interrupted as the door was pushed open by two men in civilian clothes, members of the Gestapo. They demanded that Bonhoeffer follow them. For the prisoners, this had come to mean only one thing: he was about to be executed. Bonhoeffer took the time to bid everyone farewell. Drawing Best aside, he spoke his final recorded words, a message to his English friend, Bishop Bell: “This is the end—for me, the beginning of life.”

Early the next morning, April 9, Bonhoeffer, Wilhelm Canaris, Hans Oster, and four fellow conspirators were hanged at the extermination camp of Flossenbürg. The camp doctor, who had to witness the executions, remarked that he watched Bonhoeffer kneel and pray before being led to the gallows. “I was most deeply moved by the way this lovable man prayed, so devout and so certain that God heard his prayer,” he wrote. “At the place of execution, he again said a short prayer and then climbed the steps to the gallows, brave and composed.… In the almost fifty years that I worked as a doctor, I have hardly ever seen a man die so entirely submissive to the will of God.”

In the distance boomed the cannons of Patton’s army. Three weeks later Hitler would commit suicide, and on May 7, the war in Europe would be over.

The Nazism against which Bonhoeffer struggled would linger in other forms of systemic evil in the modern world. But his witness to Jesus Christ lives on. Bonhoeffer continues to challenge Christians to follow Christ to the cross of genuine discipleship and to hear the cry of the oppressed.

Dr. Geffrey B. Kelly is professor of systematic theology at La Salle University in Philadelphia and author of Liberating Faith: Bonhoeffer’s Message for Today (Augsburg, 1984).

Copyright © 1991 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine.Click here for reprint information on Christian History.