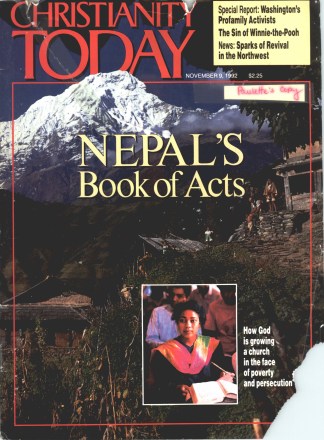

A church grows in the face of poverty and persecution.

ARTICLE BY BARBARA R. THOMPSON1Barbara R. Thompson is a writer living in Decatur, Georgia.

For four-year-old Amit, lying in rags on the floor of a thatched-roof hut in Nepal, the future appeared short and bleak. His mother was dead of tuberculosis. His father wandered village streets, out of his mind. Severely malnourished and infected with glandular tuberculosis, Amit was too weak even to disturb the flies covering his face. Death seemed certain—and kind.

Today Amit is a bright, energetic ten-year-old, flying kites and playing caroms in the shadow of the Himalayas. His favorite subjects are science and art. Gifted with a near-photographic memory, he is the top student in his school. “I want to be a doctor,” says Amit. “I want to serve the sick people of my country.”

Amit is among hundreds of young Nepalese whose lives have been transformed by the work of Ram Sharan Nepal, a 33-year-old Nepalese pastor. With his wife, Meena, Ram provides a home and education to over 150 orphans. He is also a pastor, Bible-school teacher, the supervisor of 96 churches, and the director of a vocational training program for Nepal’s poorest citizens.

These tasks, difficult in any country, are complicated in Nepal by devastating poverty and the antagonism of the ruling class toward Christianity.

The playland for some of the world’s richest tourists, Nepal is one of the poorest countries in the world. Per capita income is $80 a year. One in five children die in the first few weeks of life. Two of three Nepalese live in crippling poverty, their lives contracted by tuberculosis, malnutrition, contaminated water, and lack of medical services.

The poverty of Nepal, the world’s only Hindu kingdom, is reinforced by a rigid caste system. Of the country’s 20 million citizens, 5 million are “untouchables”—shoemakers, tailors, street sweepers, toolmakers, and garbage collectors belonging to the lowest Hindu caste. Despite laws against caste discrimination, untouchables are locked at birth into a cycle of misery with no parallel in the Western world.

“Perhaps in light of religious and cultural traditions, untouchables can accept their lot in life,” says Ram. “But when you know a better way, it breaks your heart to see the children, with their closed expressions, struggling to find their next meal. They are born into an atmosphere of virtual imprisonment.”

While untouchables pay for the sins of a “previous existence,” Nepal’s higher castes reap the rewards of underpaid labor. Living in relative affluence, they use religion to cement their political and economic power. Ironically, even the head of Nepal’s still-thriving Communist party is a Brahman, a member of Hinduism’s highest caste.

Assured of Hindu beliefs of moral superiority, Nepal’s ruling elite rightly perceives the simple Christian message of love and grace as a radical threat to the social order. Until Nepal’s democratic revolution in February 1990, evangelism and Christian conversion were crimes punishable by imprisonment and even death.

It was in this closed society that, at the age of 15, Ram Sharan Nepal became a follower of Jesus. The son of a Hindu farmer from northwest Nepal, Ram spent his childhood tending goats and rising early to offer sacrifices to Hindu deities.

“I saw firsthand the way religious leaders were robbing poor people,” recalls Ram. “For me, Hinduism was an ‘outside’ religion. I was looking for a religion of the heart.”

Ram was introduced to Christianity by a classmate, the son of a pastor from Finland. “I was drawn by the simple message of Jesus,” remembers Ram. “Christianity was about grace, not sacrifice. It gave me a way to help people.”

Shortly after his conversion, Ram’s brother tried to kill him. Ram fled his family’s home and moved to Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal. Living alone and working full-time, he found spiritual and emotional support in a small underground church of teenagers. By the age of 17, Ram was a pastor, praying for the sick and discreetly visiting new converts.

“We were like the church in the Book of Acts,” remembers Ram. “We were the first generation of Christians in Nepal, and we treated one another with love and care.”

At 20, Ram went to India for Bible college. Four years later he returned to Nepal and married Meena, a registered nurse who also had been a teenage convert in the underground church. Together, the couple pioneered a new house church in Kathmandu.

The same year Ram and Meena adopted their first orphan. “He was an eight-year-old child, wandering the streets out of his mind,” recalls Ram. “He broke the windows in our home and wrote obscenities on the wall. But today he teaches primary school and plans to go to Bible college.”

Within two years, Ram and Meena were caring for over 30 children. Meena nursed malnourished, tubercular children around the clock, and eventually she and the couple’s newborn daughter contracted tuberculosis. Both recovered with medical care.

Meanwhile, social revolution was sweeping Nepal, and Ram and Meena’s house church grew rapidly. Its members were largely young professionals, willing to risk imprisonment to practice a new, more democratic religion. Ram himself was frequently arrested. On one occasion he was jailed and beaten for two weeks.

“My role model in suffering was a witch doctor, Rishin Lama, from southwest Nepal,” says Ram. “When he converted to Christianity, hundreds of villagers followed his example. Rumors of mass conversion reached the government, and Rishin was jailed and beaten for nine months.

“He still has the physical scars of his beatings,” adds Ram. “Rishin Lama is a gentle spirit, and I learned from him how to tolerate hardship and torture for Christ.”

By 1988 Nepal was on the edge of revolution, and the government turned its attention from church leaders to political activists. After months of unrest, the traditionally peaceful kingdom erupted into armed conflict.

In February 1990, bloody street demonstrations ended the absolute rule of King Birendra, a Brahman and Harvard graduate whom many Nepalese still regard as an incarnation of the Hindu god Vishnu.

“The new government immediately released Christian prisoners,” reports Ram. “Christians were given the right to worship and observe religious holidays. But the constitution still forbids evangelism or conversion.” For Nepal, freedom of religion remains a fragile gift, whose future depends on the outcome of the slow evolution of culture and social customs.

In The Shadow Of The Himalayas

An avalanche of rocks, boulders, and topsoil thunders down a sheer cliff, spilling onto the road below. A carload of tourists screeches to a halt. A hundred feet above their heads a dozen or more workers, some only children, stand on narrow rock paths, swinging pickaxes and shovels to break away the side of the cliff.

When the avalanche subsides, workers move in to clear away the debris. The children shovel their back-breaking loads in teams: one child pulls with a chain; another holds the shovel and pushes. A rail-thin girl, not more than ten years old, brushes a wayward strand of hair from her face. Her skin and ragged yellow dress are covered with layers of dirt. She coughs, trying to clear the dust from her lungs.

The tourists are on their way to view the 26,000-foot peaks of the Annapurna Mountains. Their unscheduled stop gives them time to absorb a breathtaking panorama: a river running through a rock gorge, bright-green rice paddies, terraced mountain fields, a grove of banana trees.

The workers are “kulies,” untouchables who work year-round to maintain avalanche-prone roads for travelers. They live in makeshift tents and shacks at the edge of the road, breathing the parasite-ridden dust kicked up by passing vehicles. For their cruel labor, kulies earn $2 a day, an above-average income in Nepal. It is enough for a diet of only rice and dahl (lentil soup). But it is not malnutrition or even years of back-breaking work that takes the lives of most kulies. Rather, it is the dirt and dust that covers their homes, their clothes, their skin, and eventually their lungs.

It’s Sunday morning in Kathmandu. The monsoon has come and gone, and brightly colored kites rise and dip in the sky.

In a small, second-story room, Ram Nepal and a congregation of 80 first-generation Christians sing hymns and pray in unison. Light streams in open, unscreened windows.

Not many months earlier, the church was underground. Members arrived one by one, slipping quietly into the building. Windows were shuttered. Prayers were said in whispers. More than one service was interrupted by a visit from the police.

Today sounds of worship echo on the street. A guitar and a harmonium attract the attention of bicyclists and pedestrians. A young man leans against a tree, listening intently as Ram tells the parable of the prodigal son.

“Since the revolution, church attendance has doubled,” says Ram, who supervises dozens of churches in remote mountain regions. “People are no longer afraid of going to jail, and the poor are becoming educated. They are thinking critically about religious beliefs that oppress them.”

The church’s rapid growth has led to an acute shortage of trained leaders. In 1991, Ram began a Bible school to provide young Nepalese men and women with classes in Bible, theology, church history, counseling, and church planting.

“The younger generation is looking for a change,” says Paul Narayan Rana, a 20-year-old studying at the Bible school. “They have a lot of questions that Hinduism and Buddhism cannot answer.”

A Young Voice Of Hope

Min Raj, 20, is a student at a Bible school in Kathmandu founded by Ram Nepal. As a 17-year-old, Min Raj was a catalyst in the evangelism of his village. Today he returns to his village every two weeks to lead church services and evangelize surrounding villages.

When I was 10, my mother died in childbirth. My father is a farmer from Hindu’s highest caste. I grew up treating untouchables with utter contempt. I thought they were worthless and would not allow them to enter my home.

When I was 16, I was in a gang. We did a lot of drinking and smoking. We beat people up. One day some evangelists came to my village. It was against the law, but they went house to house telling people about Jesus. I began reading the Book of Matthew. After one year I came to know Jesus was the Savior. I was the first person in my village to become a Christian. People ridiculed me.

Then my friend became a Christian. We went from house to house, telling people about Jesus. They were happy to hear he was the sacrifice. They did not have to take a goat or chicken to the temple.

Many times the police threatened me, but I was not afraid. I knew one day truth would win. Now 500 people in my village are Christians. Four other gang members are in Bible school. More would like to come, but they have a financial problem.

Because of Christianity, my life is changed. From the Bible I learned that God created all mankind. Man is not big or small because of the caste system. This is how I began to sympathize with poor people, to treat all people the same.

My wife and I were married when I was 16. She was 15. In Hinduism, women are just the ornament of men. They must literally worship their husbands. Before I became a Christian, I thought women were slaves. But I read in the Bible there is no difference between men and women. In domestic work or preaching work, we are all equal. Now I help my wife with her work, and she helps me with mine. We are partners.

In Hinduism, before a woman becomes a Christian she is limited to domestic work or farming. But in the church, she can teach and take part in the spiritual and social effort.

I am optimistic about the future of Nepal. In my village we are planning many projects, including education, forestry, and vocational training. We want to evangelize the other villages around us and train Christian leaders.

On weekends, like many other students, Paul is an itinerant pastor and evangelist, making the long trek to remote mountain villages to lead church services and Bible studies. He welcomes the freedom to worship openly but is realistic about the pace of social change.

“There is still family and social persecution. I might not be put in jail, but I might not be able to get a job, either.”

The maturity and commitment of student workers like Paul gives an early-church quality to Nepal’s indigenous Christian community. It is a spirit that Ram hopes to keep alive even as the church loses its underground character.

“A problem in the Asian church is that people go to seminary and come out identifying with material things rather than the life of the people,” reflects Ram. “I tell my pastors, I have no salary system. I cannot guarantee your pension. I can only say, If I eat, you’ll eat. And sometimes I don’t eat.

“As long as I am alive, I will not allow a spirit of institutionalization in my church. We must always be a loving community, caring for one another.”

Ram and Meena model this caring community within their own home. In the last year, the number of orphaned children in their care has grown to 150. Sixty live with Ram and Meena and have been adopted. Another 90 fill an overflow building near the church. Most of the children are untouchables from city streets and remote mountain villages.

“One in seven children in Nepal is orphaned,” says Ram. “And 60 percent of the population is under 20. The situation is so desperate, we had to hire a gatekeeper to keep people from leaving children by our door.”

Like most visionaries, Ram has more dreams than money or volunteers. He plans to expand his children’s ministry to serve 3,000 orphans. He is pioneering an occupational-training program for untouchables and women. He eventually hopes to develop a Christian college and plant hundreds of churches throughout Nepal.

Meanwhile, at “the rooftop of the world,” the ceiling of opportunity remains hauntingly low. Nine of ten Nepalese make their living on small farm holdings. With the population growing by 2.6 percent per year, farmers in search of arable land move higher up the fragile Himalayas. Nepal’s topsoil, the life of future generations, has become its chief export, washing all the way to Bangladesh.

“When I go to villages, what I see is a picture of hell,” says Ram. “I am surrounded by people without enough to eat, who are sick and without hope for the future.

“If I were not a Christian I would not live in this country,” he adds candidly. “Poverty is a spiritual death, and I could not face the suffering every day. But God always puts his face on people, and it is his love which compels me.”