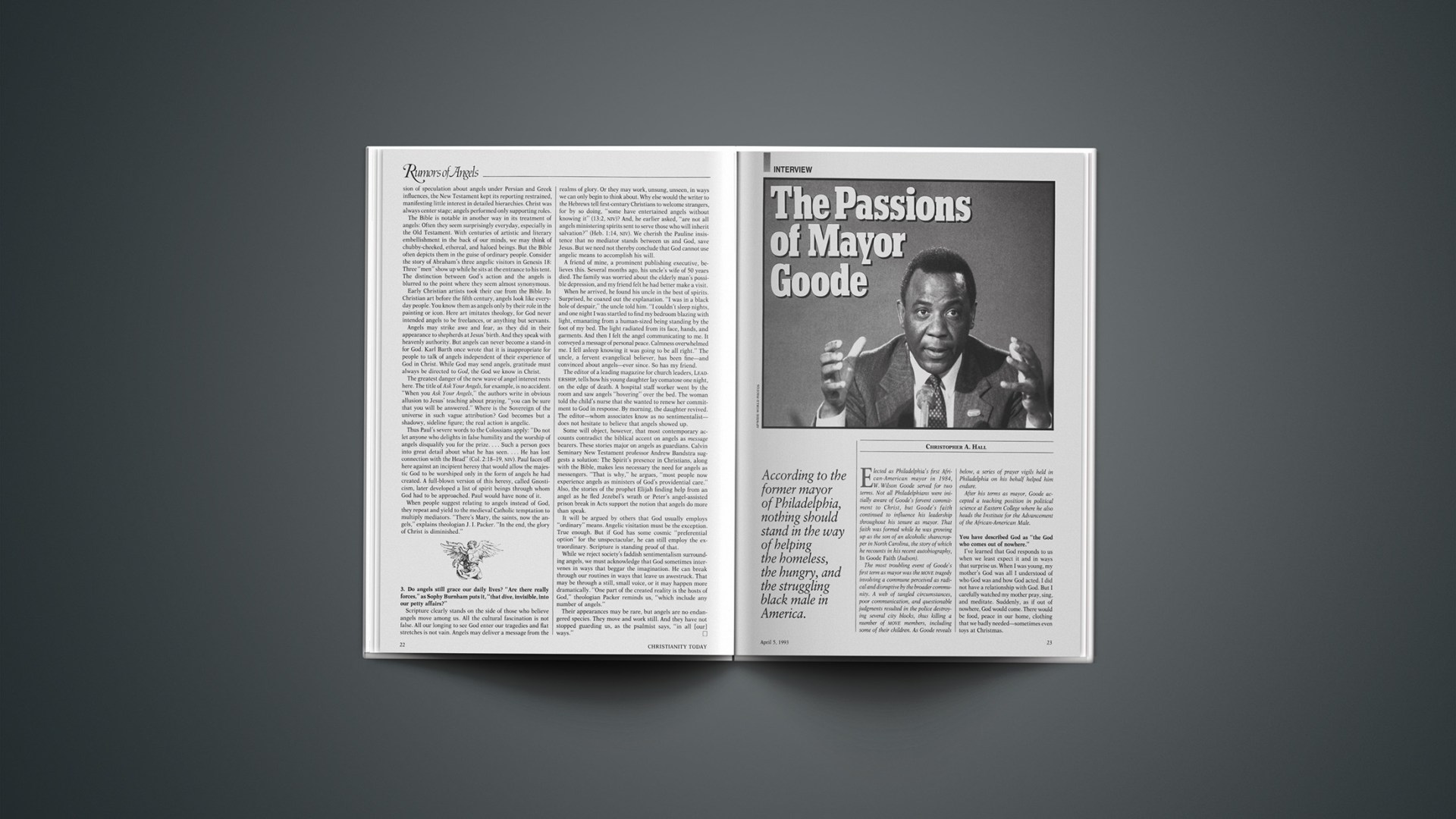

According to the farmer mayor of Philadelphia, nothing should stand in the way of helping the homeless, the hungry, and the struggling black male in America.

Elected as Philadelphia’s first African-American mayor in 1984, W. Wilson Goode served for two terms. Not all Philadelphians were initially aware of Goode’s fervent commitment to Christ, but Goode’s faith continued to influence his leadership throughout his tenure as mayor. That faith was formed while he was growing up as the son of an alcoholic sharecropper in North Carolina, the story of which he recounts in his recent autobiography, In Goode Faith (Judson).

The most troubling event of Goode’s first term as mayor was the MOVE tragedy involving a commune perceived as radical and disruptive by the broader community. A web of tangled circumstances, poor communication, and questionable judgments resulted in the police destroying several city blocks, thus killing a number of MOVE members, including some of their children. As Goode reveals below, a series of prayer vigils held in Philadelphia on his behalf helped him endure.

After his terms as mayor, Goode accepted a teaching position in political science at Eastern College where he also heads the Institute for the Advancement of the African-American Male.

You have described God as “the God who comes out of nowhere.”

I’ve learned that God responds to us when we least expect it and in ways that surprise us. When I was young, my mother’s God was all I understood of who God was and how God acted. I did not have a relationship with God. But I carefully watched my mother pray, sing, and meditate. Suddenly, as if out of nowhere, God would come. There would be food, peace in our home, clothing that we badly needed—sometimes even toys at Christmas.

At what point did you make your mother’s faith your own?

I was converted in a small country church when I was 12 years old. My mother had said to me, “It’s now time for you”—she emphasized the word you—“to make your decision for Christ.” I was confused. I needed to make a decision for Christ? As I sat on the mourner’s bench in church, I began seriously to consider my mother’s words. I had always feared God. I thought that if I failed to obey God, God would strike me dead. And yet as I sat on that mourner’s bench, I sensed I was coming closer and closer to Christ as he drew near to me.

It was as if Christ grabbed me and said, “Now you’re ready to serve me. Get up and take your minister’s hand and confess your sins before all these people.” I was being born again. I was a new creature. I literally changed my life from that point on. I was not as mean-spirited or mischievous as I had been before. I was more thoughtful about myself and others. I had no doubt that the Holy Spirit was moving in my life on that mourner’s bench and has been moving in my life since that time.

How has your relationship with Christ influenced your career choices?

At one time I decided to become a management trainee. My main goal was to make a lot of money. However, the job simply didn’t fit me. It was as though someone kept saying to me, “This is not where you belong.” Within 18 months I had returned to work in the city, even though this change meant I would be making less money. Basically, I ended up sitting in an office analyzing community organizations. The knowledge I gained would prove invaluable during my tenure as mayor.

I also sensed the Spirit’s guidance as I took the mayor’s office. As managing director for the city of Philadelphia, I had become something of a sensation for my ability to manage the budget and cut expenses. However, as I faced firsthand the problems of homelessness, AIDS, and child abuse, God hit me right between the eyes. The twenty-fifth chapter of Matthew kept coming back to me—that we were called to feed the hungry, house the homeless, and visit those in prison. I was driven, absolutely driven, to create one of the best programs in the country to protect homeless people. I had a responsibility beyond my oath of office. I had an obligation to God not to allow people to freeze to death and die of hunger.

The last time I strongly sensed the Spirit’s guidance was as I contemplated what to do after my time as mayor. A company in New York offered me an obscene amount of money to be its lobbyist on local governmental issues. I also talked to people at Princeton and Harvard about teaching positions. These were all prestigious positions, extremely lucrative and quite attractive. Instead, though, I decided to set up a nonprofit group to help African-American males. I started teaching at Eastern College. My wife said to me, “What is wrong with you?”

I said, “I don’t know what is wrong with me. All I know is that this is what I want to do with my life.” There is no logical way to explain these decisions apart from God’s movement in my life.

While you were mayor, how else was your faith strengthened or challenged?

My faith was both challenged and strengthened when I first ran for office in 1984. Early that year I had to decide whether to support Jesse Jackson or Walter Mondale for the presidency. The prevalent view was that I should support Jesse because he was black and I was black. I chose, though, to support Mondale because I thought this was the best decision for the city, rather than for me politically. I took a lot of heat from people for making this decision, but I felt it was the right decision, and I won the election.

Another key juncture occurred after the MOVE controversy. After this event, few people gave me any real chance for future political success. A local pastor, the Reverend Louise Williams, began to hold a series of prayer vigils throughout the city on my behalf. Nothing has ever strengthened and enhanced my life like those prayer vigils. Men and women, black and white, came together all over the city for four or five consecutive weeks to pray for my well-being, for the will of God to be fulfilled in my life, and for my spiritual health. I contend that because I was willing to accept these prayer vigils as God speaking to me that I went on to win a second term as mayor. I emerged from this time believing not only that I should run for a second term, but that I would win. It was one of the most spiritually fulfilling periods in my life.

How have you personally dealt with the MOVE tragedy?

I have asked God for forgiveness for my impatience, my lack of judgment in the appointment of the police commissioner, for the loss of life, and the role I played in this event. I believe a prayer for forgiveness asked in earnest is granted by God and that God has forgiven me. Peace with God, however, doesn’t guarantee peace with the broader community. I’ll be experiencing political punishment because of the MOVE incident for the rest of my life, but from a Christian perspective, I’ve been forgiven and have peace with God.

You are presently focusing your attention on the plight of the African-American male. Why?

In my eight years as mayor, the people I saw most at risk were African-American men. Seven out of ten African-American men between the ages of 17 and 44 are at risk—at risk of homelessness, AIDS, of dying violently in the street, of going to prison, of unemployment, of drugs, of illiteracy, of abuse in foster homes and in their own homes. One out of twenty black boys born in America today will be killed before he reaches his twenty-first birthday. If we’re going to change this statistic over the next ten years, we have to intervene now in the lives of young African-American boys in the inner city.

In 1940, 9 out of 10 black families had a black man as head of the household. In 1970, it was 6 out of 10. In 1992, it’s 3.5 out of 10. This should not surprise us if 7 out of 10 African-American males are at risk. So I want to work to bring back a complete black family. If we support family values, surely we’re talking about working to bring these families back together so they can have a wholesome life. This is the central project I’m working on.

How will this concern be expressed in your work with the Institute for the Advancement of the African-American Male at Eastern College?

No other university or college in the country is producing hard research on the plight of the African-American male. The institute at Eastern will provide the research foundation for future public-policy analysis of this grave problem. We will then be able to travel across the country disseminating this data and urging people to take action. We can think about this problem in emotional terms all we want, but until we get hard data and examine carefully reasons and causes, little will be accomplished.

What steps can the evangelical church take to overcome racism in our society?

All of us have been molded by our environment, culture, and background. We all create a “line of separation” from people who are different from us. This line of separation reinforces our ignorance of other groups and undercuts mutual understanding. This line can be cut if white Christians begin to fellowship with African-American Christians, Asian Christians, and Hispanic Christians.

During a recent Billy Graham crusade in Philadelphia, over 1,000 white men visited the Cornerstone Baptist Church in North Philadelphia to worship with the African-American community there. Although this was their first visit, 89 percent said they enjoyed the fellowship, worship, and music.

What are the needs of the inner city that the church is called to address?

All Christians need to examine carefully three central concerns: hunger, inadequate clothing, and homelessness. We can begin to alleviate these problems without getting the government involved. To fight a drug war, you have to involve the government. To rebuild major parts of our cities, you have to involve the government. But not to address the problem of hunger. Not to provide adequate shelter for homeless families. Shelter is available in churches, in properties owned by churches, in facilities churches can lease out. There is enough clothing in our closets to clothe all the people who don’t have adequate clothing—clothing we don’t need and will never wear again. But what do we do? We sell this clothing at garage sales.

We must rebuke our inherent selfishness by the power of the Holy Spirit. If Christian leaders in this country stood up and said in unison that we must wipe out hunger, hunger would be wiped out. Every religious leader should admit and proclaim that homelessness is a blight on the face of our country. How can Christians ignore the people who sleep in gutters and alleys downtown? How can we ignore them when we have cathedrals and churches that could house them for the night?

Many evangelicals feel alienated from the Democratic party because of its positions on abortion and homosexual rights. As a Democrat, do you feel this tension?

I feel a real tension. It is difficult from a Christian perspective to support the abortion-rights people. I believe that conception is a gift from God. As a Christian, I don’t believe anyone has the right to interfere with this process. On a public-policy level, however, does the government have the right to step in and tell individuals what they must do with their own bodies? I would state categorically that, as a Christian, I could not take a life, regardless of what point in the pregnancy the abortion takes place. I feel free to tell anyone my Christian views. But I have a difficulty saying that nonbelievers must agree with my perspective.

As for homosexuality, I reject the homosexual lifestyle while maintaining that homosexuals must still be treated as human beings. Homosexuals have the same fundamental human rights as any other human beings on the face of the earth. I will always defend their right to live where they want, to eat where they want, and to be fully accepted as human beings in our society.

What advice would you offer Christians considering political office?

I would tell them what I told my son. Public service is a noble profession that needs people of honesty, integrity, commitment, and vision. Know it will be hard, because you will be different. Fight for your position. Don’t give an inch. Don’t compromise your principles for the sake of political expediency. Even when an overwhelming number don’t believe in what you stand for, don’t give up. We need Christians in the public arena fighting for Christian principles, for right and wrong, for social issues, for honesty and integrity. This can only happen if we have politicians who are motivated, not by selfish interest, but by the larger interests of the community.

Loren Wilkinson is the writer/editor of Earthkeeping in the ’90s (Eerdmans) and the coauthor, with his wife, Mary Ruth Wilkinson, of Caring for Creation in Your Own Backyard (Servant). He teaches at Regent College in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.