As L.A. and other urban areas simmer with racial tension, many Christians ask, “What does the church have to offer?” The past two decades have seen countless multiracial prayer breakfasts, pulpit exchanges, and formal declarations of reconciliation. Evangelical Christians can point to many places where blacks, whites, Latinos, and Asians are worshiping and ministering in harmony and as equals.

Despite these attempts, however, Christians remain as racially separated as the rest of society. It is still true that 11 o’clock Sunday morning is the most segregated hour in America. It is a costly separation. When African Americans speak frankly to their white counterparts, they express deep hostility and frustration. They feel angry, hurt, and betrayed by what they see as society’s and the church’s failure.

Many white Christians are bewildered by these strong feelings. They wonder what nonwhites want. Many white evangelicals do not feel they are racist, and they say they very much want for all colors to be united in their faith. Writes Jay Kesler in his foreword to William Pannell’s book The Coming Race Wars?, “Frankly, I thought we were doing better.”

Yet black anger is an undeniable reality. So are the economic facts of life for African Americans. While many middle-class blacks have improved their situation, their experience is not the norm. As a group, African Americans are, by some economic measures, worse off now than at the height of the civil-rights movement. For instance, the unemployment rate for blacks in the late sixties averaged 7 percent, but in 1990 it was 11 percent (comparable figures for whites are 3 percent and 4 percent). Today, nearly one in four black men between 20 and 29 years old is in prison, paroled, or on probation; 9 percent of whites and 32 percent of blacks are poor; the infant mortality rate for blacks is twice that of whites; whites live, on average, six years longer than blacks.

Clearly, the racial divide is a grievous problem for America—and for the church (whose reputation is tarnished by a history of racial splits within its institutions).

The frustration goes beyond statistics. African Americans describe daily humiliations in the most mundane situations.

One black executive within a mostly white evangelical organization tells how she recently was told her teenage son can’t date a white colleague’s daughter. A black evangelical family recounts moving into a new house in DeKalb County outside Atlanta. Within a week their white neighbors on either side put up their homes for sale. For every positive statement about race by church leaders, there are countless painful incidents on buses, in classrooms, hallways, board-rooms, and churches.

Black leaders warn that we could be at a point of no return. Writes Spencer Perkins in More Than Equals: “A new phenomenon is growing among blacks who are frustrated with the reality of integration: a call for black separation.” Pannell writes in The Coming Race Wars?, “Ultimately, the [nonwhite] church in the city will have to go it alone.”

If this were to happen—if black and white Christians were to grow permanently, angrily separated—what would God’s people have to offer to a racially torn world?

Racial complexity

Only to look at black-white problems is, of course, too simple. Richard Rodriguez, a leading California essayist, says, “The Kerner Commission Report’s conclusion in 1968 that there were two nations in the U.S., one black, one white, separate and unequal, simply does not fit today.” With the explosion of the Latino population, who by the year 2010 will outnumber blacks, and the great influx of Asian immigrants, America’s racial situation has become much more complex—and more urgent. Both whites and blacks face new, bewildering ethnic diversity that they cannot avoid.

It is also true that nonwhites have their own racist attitudes to work out. Koreans and Latinos have well-documented racist attitudes toward African Americans. Blacks carry negative stereotypes of Koreans (as witnessed in last year’s L.A. riots) and are participating in black flight from communities turning increasingly brown or yellow in cities such as L.A. and Chicago. Their response parallels that of whites who fled neighborhoods when blacks began to move in.

In this CT Institute, however, we have deliberately focused on white-black relations. These groups have the longest and most complex history in the U.S. church. Unless they can resolve their differences, there is little hope for reconciling ethnic groups that have less shared experience.

Hearing voices

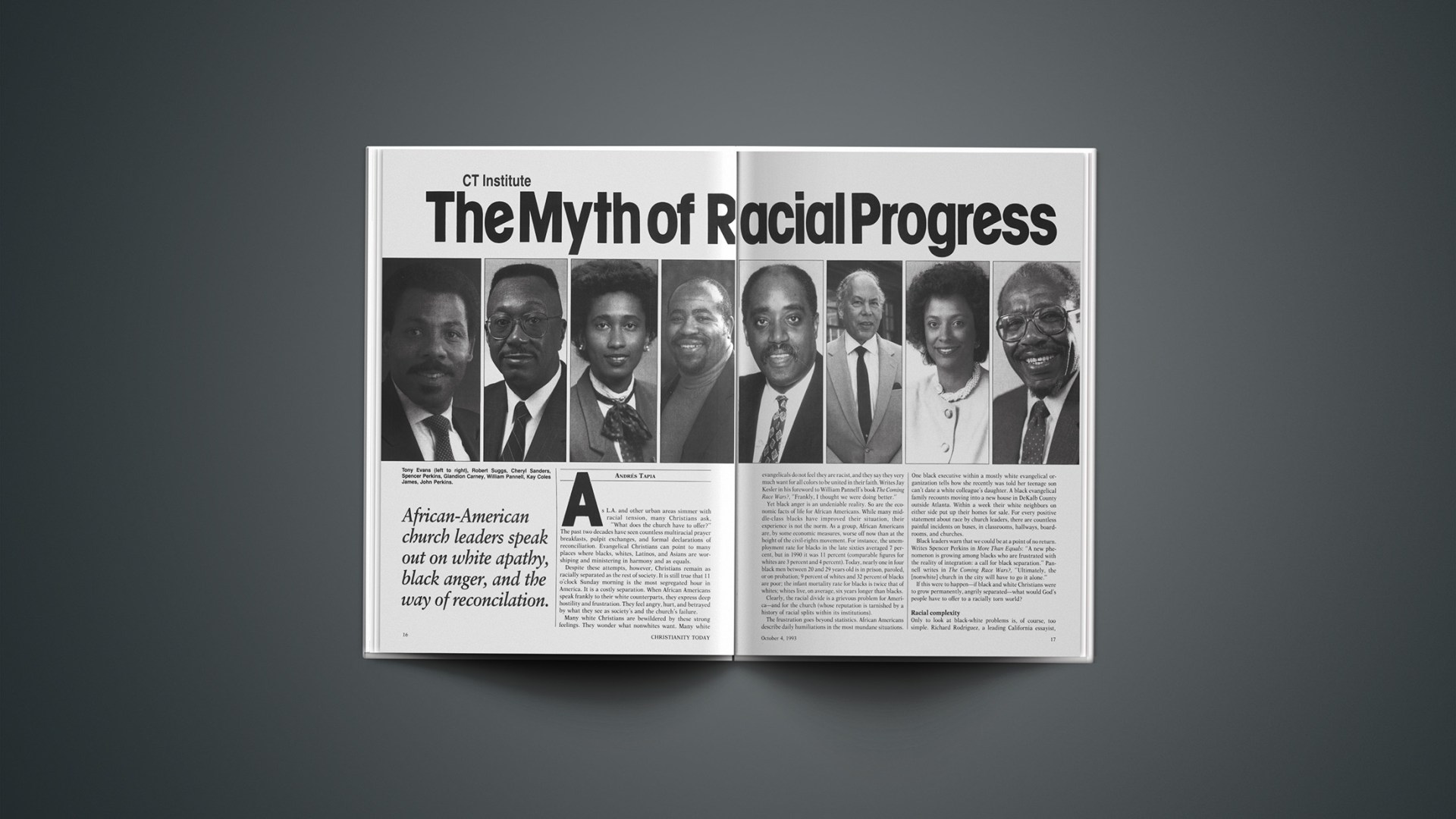

We asked 41 African-American Christian leaders—most of them evangelicals—to address the white evangelical community. We asked them, “What do you want your white evangelical brothers and sisters to hear right now?” A selection of those responses are excerpted below. We also collected selections from recent books by black church leaders for narratives and insights to illustrate why African-American Christians feel such anger and frustration.

White readers, we suspect, may be tempted to find reasons to discount these statements. The words are personal and emotional, strong and shocking. Some are hopeful, but most are angry.

The dynamics between blacks and whites are in many ways similar to those of an estranged couple. Often the problem is not some single tension-causing incident but lies with a pattern of behavior. If one of the parties consistently feels rejected or ignored, then something is certainly wrong. Rebutting the angry emotions may not help. Sometimes, as in marriage counseling, it is necessary first simply to listen long and hard—and not to interrupt with objections. Then, after the message is heard, we can go on to ask, “What can I do to make this better?” In this institute we invite our readers to listen.

Andrés Tapia is a senior news writer for Christianity Today. Research for this project was partially funded by a grant from Religion News Service.

Something Is Wrong at the Root

John Perkins, founder of the John M. Perkins Foundation for Reconciliation and Development, and publisher of Urban Family magazine.

Something is wrong at the root of American evangelicalism. I believe we have lost the focus of the gospel—God’s reconciling power, which is unique to Christianity—and have substituted church growth. We have learned to reproduce the church without the message. It is no longer a message that transforms.

It reminds me of the white Christian sailor in Roots who went on a slave cargo ship to earn enough money to get married. The church-growth philosophy of homogeneity is a heresy that, like that young sailor, has sacrificed principle for expediency. That approach has encouraged the separation of the church rather than reconciliation with God, each other, and the world—which is the church’s mission. There is no biblical basis for a black, white, Hispanic, or Asian church.

I wish the church could come to grips with its mission: to repent and turn to the poor. Jeremiah proclaimed this message through tears. We need some living examples to stand up and be willing to accept the persecution that goes with preaching this message. But I know that as with Jeremiah, those receiving the message will want to brand the messenger “angry” so they don’t have to hear what he or she says.

Separate Vacations

Kay Coles James, executive vice-president of the Family Research Council in Washington, D.C., and the author of Never Forget (Zondervan).

I became involved in a women’s Bible study that met once a week at a white church. One of the highlights of the year was a trip to Myrtle Beach with the families of the women in our study. All year long references to the annual family beach trip were dropped into conversation. I had heard so many stories about the fun times they had together that I was really looking forward to going. But we were never invited. As summer drew near, I overheard women making arrangements for shared beach houses, but the conversation would die down whenever I came near. The group left for the beach without us, and I was crushed. I’d never felt so betrayed and rejected.

Eventually embarassment and hurt died down enough for me to ask one day in Bible study why Charles and I weren’t included in the beach trip. An uncomfortable silence fell upon the room. “Well, Kay, we just felt that—well, you know that there aren’t very many black people at Myrtle Beach … and we just thought you would be uncomfortable.” They were concerned about us? Didn’t they see the irony? It took all my courage to read our Scripture verse out loud before the group, but I wanted to say something else. I did. “I guess I thought that if we wouldn’t be accepted at a certain vacation spot, that you would choose another one rather than leave us out.” Nothing more was ever said about it.

Silent Whites, Dying Blacks

Hycel Taylor, senior pastor of Second Baptist Church in Evanston, Illinois.

For us, as an African-American people, we have to ask some serious questions. What’s going wrong with us? Not so much in relationship to white people, but in relation to ourselves. What’s so stigmatic in our minds that we have now turned on ourselves and begun to kill each other, where now we become our own lynch mobs? We’re looking at genocide so insidious that if we quantified the dying of African Americans just for 24 hours across this nation, we’d need to call for a state of national emergency. We’re dying of AIDS; we’re dying of hypertension; we’re dying as stillborn babies; we’re dying from drugs.

What’s happening to white America? How can it be that a David Duke would rise to any semblance of power in this country today? As Martin Luther King quoted, “All you need for evil to triumph in the world is for good people to do nothing.” Will the white church be silent as these things occur?

Is it possible for the races to rise above their differences and yet not ignore the diversity? Yes, we can. And we can do it because Christ is in our lives, and Christ rises above all of us.

The Issue Is Sin

Robert Suggs, academic vice-president at Grand Rapids Baptist College.

When I pastored an urban black church in Rochester, I frequently got a particular kind of call from the white pastors in the area. They would say, “We have the name of a family you might be interested in.”

Invariably, when I followed up on the referral, it was a black family that had visited the white church. The white pastors who called me often assumed the black family had come to their church by accident, or that they would not feel comfortable there. But these families often told me they had gone to the church because it was in their neighborhood and that they had not requested a referral to a black church.

It’s distressing that white evangelicals seem unable to see the reason for the troubled relationship with their African-American counterparts. Why is there an estranged relationship between these two groups that agree with each other in the fundamentals of Scripture and basic lifestyle issues? It is, quite frankly, sin.

It is clear to many African-American evangelicals that their white counterparts are operating under a redefinition of sin. It’s a redefinition that does not see as sin that few African-American students and educators can be found at our nation’s approximately one hundred Christian colleges and Bible schools; that does not see as sin congregations leaving their urban neighborhoods and their unsaved residents in an effort to pursue homogenous groupings; that does not see as sin the persistent reality of 11 o’clock Sunday morning being the most segregated hour in America. The evangelical church has never repented of these historical, social, and personal sins of racism. To a large degree, it continues the practices, but now more subtly and in many situations, not at a conscious level. It is time to put the past behind us and to repent of the sins of all of our fathers and for the indulgences and insensitivities of our own lives.

You Can’t Dismiss Martin Luther King

Dale Jones, executive director of Quest Atlanta ’96, a multiracial ministry serving the community and visitors for the 1994 Super Bowl and the 1996 Olympic Games.

Martin Luther King, Jr., continues to be suspect among white evangelicals because of his education in liberal seminaries. What many whites don’t realize is that conservative Christian colleges barred blacks from attending their schools for decades, leaving African Americans who felt a calling into the ministry with few options. The liberal seminaries were the ones that opened the doors to them. Martin Luther King spoke prophetically about America and gave his life up to seek a Christian ethic in this land. If African Americans who love Christ honor King, then for whites to dismiss him is to disrespectfully dismiss the judgment of a whole group within evangelicalism.

Needed: An At-risk Gospel

Cecil “Chip” Murray, senior pastor, First African Methodist Episcopal Church, Los Angeles. Murray’s 10,000-member church was the focal point of relief efforts during last year’s L.A. riots and was named one of President Bush’s Points of Light.

White evangelicals need an at-risk gospel for at-risk people in an at-risk society. Calling sinners to repentance means also calling societies and structures to repentance—economic, social, educational, corporate, political, religious structures. Why is the neighborhood church not doing nightly patrols of its own neighborhood, where illicit drugs are sold? Why are we not housing the homeless whose sleeping forms we step over to gain admittance to our churches? Where are our prison ministries, our substance abuse or mentoring or ethnic crossover or counseling ministries? Why are we not more at risk?

Personal salvation is never divorced from social salvation because personal sin is never divorced from social sin. The gospel at once works with the individual and the individual’s society: to change one, we of necessity must change the other. Even as the individual makes bad decisions, so do their decisions result in part from decisions made by a bad society.

Hitting Bottom

Dolphus Weary, director of Mendenhall Ministries in Mississippi and the author of I Ain’t Coming Back (Renaissance), from which this was adapted.

Things hit bottom one day when somebody at the mostly white Christian college I was attending came up and told me, “Martin Luther King got shot!”

“What?” I cried. “You’re kidding!” I ran to my room and flipped on the radio. The newscasters were talking about it. I was devastated.

As I sat there on my bed, I overheard voices down the hall, talking about it—talking about how glad they were that Martin Luther King had been shot! What am I hearing? I wondered, incredulously. What is this? I thought this was a Christian school, and here are these kids talking about how glad they are that Martin Luther King has been shot!

This went on for a while. My first impulse was to rush out and confront them. These kids were sick! Furthermore, I believed that by laughing at Martin Luther King, they were laughing at me, and at all the other millions of black people that Martin Luther King spoke of. But I resisted that. I needed to get control. I felt nauseated. I was hurt, disillusioned, and angry.

Then the report came: “Martin Luther King has died in a Memphis hospital.” A cheer erupted from the group down the hall.

I’m Pessimistic

Glandion Camey, associate director of the missions department of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship.

I am very pessimistic. So much has been written on this topic, but when are we going to come together and not argue the issue and simply do what the Bible says, to do what is right regarding the issue of racial prejudice?

I’m tired of questions about this. I see no outcome, no real dealing with the issues, or doing what has been decided needs to be done. There has been very little fruit from the pledges of racial reconciliation made by evangelical groups, such as the National Association of Evangelicals and other major Christian Carney agencies. These organizations continue to be white in their structure and avoid issues that concern the cities.

Nothing has come from our great words. We seem always to fall short of being able to walk together as brothers and sisters. I am not hopeful, even though I want to be.

No Substitute for Love

Morris E. Jones, Sr., church planter and pastor of Immanuel Evangelical Baptist Church, Indianapolis, Indiana.

I believe many white evangelicals have an intellectual understanding of agape love, but lack heart knowledge of it. There seems to be right theology and the right religious works, but they do not understand that there is no substitute for love. Love must be practiced! Matthew 5:14 says: “You are the light of the world,” referring to believers. White evangelicals have done little or nothing to help America heal the wound of racism. A dying world needs to see this light instead of seeing Christians just doing what is best for their own race.

Integration Versus Reconciliation

Spencer Perkins, editor-in-chief of Urban Family magazine. He lives in an intentional biracial Christian community in Jackson, Mississippi.

I fear that many whites assume that racial reconciliation is something blacks want from whites. It may surprise most white evangelicals to learn that black Christians are no more interested in working toward racial reconciliation than white Christians. Blacks are interested in eliminating racial injustice, in confronting racism, and in ensuring that the playing field is level, but going out of our way to build the cross-cultural relationships necessary for racial reconciliation does not evoke those same passions.

Whites also should not confuse racial reconciliation with integration. Integration was a political pursuit that could only be taken so far. You can’t make someone accept you as a brother or sister. All you can do legally is make it against the law for them to discriminate against you. Reconciliation, on the other hand, is spiritual and must be approached as such. Somewhere we’ve got this notion that reconciliation is optional—that it is okay for us to witness to the unbelieving world a gospel that is too weak to bridge racial barriers.

The evidence of our love for God is in our love for our neighbor. It then becomes very important to consider the answer that Jesus gave to the question “And who is my neighbor?” He didn’t just say the people of your neighborhood or the people who look like you. He told the story of the Good Samaritan.

In choosing a Samaritan, Jesus was saying that our neighbors are especially those people whom we have the most difficulty loving. It does not take much practical application to determine who Jesus would use as “neighbor” if he were talking to blacks and whites in the U.S.

For centuries, we have announced proudly to the rest of the world that Jesus (and our Christianity) is the answer for the world. Maybe we should add a disclaimer that says, “with the exception of race and culture.”

We Have Nothing to Show the World

Cheryl J. Sanders, associate professor of Christian ethics at Howard University School of Divinity and associate pastor for leadership development, Third Street Church of God, Washington, D.C.

The moral ineffectiveness of the evangelical churches on the issue of race is because many of these churches openly practice discrimination against blacks and women, especially in leadership and in determining ministry priorities. Exempt from the civil rights of the land, American churches have become a stronghold of resistance to the principles of justice and equality rather than the source of it.

We evangelicals must practice what we preach. Otherwise we’re hypocrites. We cannot despise persons who are different while we are trying to minister to them. Further, we do not have a positive Christian witness for racial justice if we have no models, no programs, no examples within our ranks to offer the world. If we were practicing reconciliation, affirmative action, and level playing fields in our churches, it would challenge our society’s dominant racist values and would give Christians something to preach to others.

Racism is a lie, and its structures and effects require the continued cover-up and double talk of some of today’s evangelical leadership.

Calling All Christians

Robin McDonald, executive director of the Capitol Hill Crisis Pregnancy Center, Washington, D.C.

God has called all Christians to the ministry of reconciliation—first, to be reconciled to him, and then to one another. Sadly, few heed the latter half of our calling. Racial reconciliation demands that we stretch ourselves past our comfort zones. Too often these attempts are casually dismissed by the white church, breeding disappointment and mistrust. Unless Christians stand together, our church and our nation will remain divided.

Whites Are Not Taken Seriously

William Pannell, professor of preaching and practical theology at Fuller Theological Seminary, Pasadena, California, and the author of The Coming Race Wars? (Zondervan).

We’re going to have to take some rather courageous and extraordinary steps to avoid a race war. The first step is sincere repentance of racism by white evangelicals. Until something like that happens, I don’t envision black evangelicals taking their white counterparts seriously.

Why Are We a Threat?

Peggy L. Jones, senior pastor of the multiracial Macedonia Assembly of God Church in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and chief executive officer of a consulting firm that conducts training for Fortune 500 businesses and churches wanting to deal with multicultural diversity.

I am African American. I am female. I am bicultural. I was raised Baptist and have been evangelical for the past 16 years. Why did God call me out of a fairly comfortable homogeneous religious environment into a different racial and religious environment? Because he truly is an Ephesians 2:14 God who is tearing down walls of hostility between groups of people.

Sixteen years later my heart still cries out to God. When will my people no longer be seen by white evangelicals as a threat? As less than? When will we be allowed to be equal with you and not oppressed by you? It is expected that the secular world continues to oppress, but not the body of Christ.

Didn’t Jesus come to set the captives free? Isn’t the evangelical heritage one of social reform and speaking out against injustices as well as leading lost souls to Christ? Where are the Jonathan Blanchards today? the Charles Finneys? the Theodore Welds? the Antoinette Browns and Amanda Smiths? the Catherine and William Booths? These were men and women who could not idly sit by when black Americans were being treated unjustly. When did the heartbeat of many white evangelicals change?

We Will Be Held Accountable

Tony Evans, senior pastor of Oak Cliff Bible Fellowship in Dallas, Texas, and founder of the Urban Alternative. His daily radio program is heard on 245 stations nationwide. He is the author of many books, including Are Blacks Spiritually Inferior to Whites? (Renaissance).

Unity is very expensive. Just as a husband and wife must give up a lot to gain the oneness that marriage offers, so also must races be willing to pay the price to experience biblical unity. One of the losses both sides must be willing to experience is the rejection of friends and relatives, whether Christians or non-Christians, who are not willing to accept the thesis that spiritual family relationships transcend physical, cultural, and racial relationships. This is what Jesus meant when he said, “Whoever does the will of my Father who is in heaven, he is my brother and sister and mother” (Matt. 12:50).

The cost is particularly expensive to local churches who begin opening their doors to people who are viewed by many as socially unacceptable, even though they have been made acceptable to the Father by the blood of Christ.

There must be the willingness to hold people accountable for refusing to cooperate with the bridge-building efforts of the church. Racism cannot be allowed to fester without public and personal condemnation. It should be clear what the church will and will not allow. What should not be allowed is the subjection of brothers and sisters who are different to racial slurs and public rejection in the church. There is no more time for us to sit by and wait for people to change. People must be led into change, and that cannot be done without the knowledge that we will be held accountable for how we treat the other members of God’s family.

Only if all sides are willing to take this stand will the effort be worth the risk. For one side to pay the price without equal commitment from the other is to create only more mistrust and division. However, when both sides take a strong biblical stand, the support systems will be there to withstand the opposition that will naturally come from taking a stand for righteousness.

Greatest Thing Whites Can Do

Edith Jones, city director of CityLine, a ministry of World Vision in Washington, D.C.

The greatest thing whites can do is ask, “What can I do?” This bestows honor and respect on us as fruitful and accomplished people. Let us tell you. Come as humble servants. One of the greatest hurts within our community is seeing caring whites come in and write about us rather than letting us tell who we are. This is usurping and castrating.

Qualified Minorities

Billy Ingram, senior pastor of Maranatha Community Church and founder and leader of the Southern California Coalition of Religious Leaders, a multiracial organization dedicated to pursuing racial reconciliation in the greater Los Angeles area.

It is an insult when whites say they would like to hire a minority person but don’t know of anyone who is qualified. Within the black community there are plenty of talented, skilled, and educated people. We have great expositors, professionals, and leaders. The problem is that whites have not networked with minorities. They have not gotten to know us. You learn more about a person sitting around a table eating their food than by watching the media.

Black Rage

Spencer Perkins is coauthor with Chris Rice of More Than Equals: Racial Healing for the Sake of the Gospel (InterVarsity), from which this has been adapted.

Most black people are angry—angry about our violent history, angry for the hassle that it is to grow up black in America, angry that we can never assume that we won’t be prejudged by our color, angry that we will carry this stigma everywhere we go (it is hardly ever a positive asset), angry that black always seems to get the short end of the stick. And most of all, angry that white America doesn’t understand the reasons for our anger.

This anger can be a very destructive force, as proved by the rioting in South Central Los Angeles after the police who beat Rodney King were acquitted. Backed up against the wall, most blacks will concede that the violence and looting were wrong. But deep in the recesses of most black minds was a tiny voice whispering, If this is the only way we can make them understand how we feel, then so be it.

As I sat in church the Sunday after the riots, a black friend passed me a note that read, “I’m kinda glad they are rioting in L.A.” My friend would never have made this statement in public.

Regardless of what you think about anger, it is present in nearly all American blacks—even in Christians like me—and must be reckoned with. If blacks and whites are to achieve long-term, intimate relationships, blacks must learn to channel their anger and reserve it to fight injustice rather than directing it at [those] whites who are sincerely trying to reach out. Whites, on the other hand, need not make it their mission to convince blacks that there is no justifiable reason for their anger. Instead, whites must seek to understand the reasons behind this anger and then learn not to fear it.

Black anger must be defused with sincere love, not negotiated like a minefield. And since the intended target of black anger is white arrogance and apathy, one of the best first steps toward healing is to build meaningful, nonpatronizing peer relationships with the targets of our anger—white brothers and sisters. It is easy to remain angry with a faceless white race. It is much harder to direct that anger at a particular white brother or sister who has a name and a face.

Learn from Us

Tony Warner, Georgia area director for InterVarsity Christian Fellowship.

The problem is simple. For the most part, white leadership has not been able to overcome the twin evils of dominance and arrogance that have historically marred hopes for biblical relationships across racial lines. For example, whites want blacks to come to their churches or organizations and learn from them, but there is very little inclination for whites to learn from African Americans in a significant way.

Only when whites are prepared to repent of dominance and arrogance in racial matters can a constructive start be made. While I do not limit the power of God, nothing in the track record gives me hope that this will happen on a broad basis. White evangelicals are more willing to pursue a white conservative political agenda than to be reconciled with their African-American brothers and sisters. It raises a fundamental question of their belief and commitment to the biblical gospel.

We Need Each Other

Samuel G. Hines, senior pastor of Third Street Church of God, Washington, D.C.

We need each other. Because of the interdependence of community, we all hold the key to other people’s freedom. White people can’t free themselves of their guilt, fears, and prejudices. Black people can’t free themselves of the oppression and injustices that have been meted out to them for generations. Racial divisions are robbing both sides. Whites not only have to be willing to help, but to be helped by the insights of a suffering people.

Whites can’t help until they have heard the cry of blacks. We’ve got to work with the anger that blacks feel, not around it. It is the church’s responsibility to take culture, race, and ethnicity seriously and teach people to appreciate differences rather than let them scare us. As we do this we’ll understand why the anger is there. And this builds trust.

Black Christians Love the Bible

J. Deotis Roberts, distinguished professor of philosophical theology at Eastern Baptist Seminary, Philadelphia, and president of the American Theological Society.

The word evangelical is a turnoff for most African-American Christians. In this country, it usually refers to a one-dimensional view of Christianity—a spiritual, privatized, vertical view. The term usually carries with it the idea that race relations are expected to be based on a sentimental love without real consideration for social justice.

Black Christians love the Bible, but it is their interpretation that differs from white evangelicals. African Americans know the Bible as a means of oppression as well as a source of liberation. We cannot assume that all Christians get the same message from reading the Bible. Only a liberating, holistic view of Scripture has an appeal for African-American Christians. There can be no genuine reconcilation without liberation and social transformation.