How 24,000 Mississippi Christians are beating racism one friendship at a time.

In Woody Allen’s Crimes and Misdemeanors, the character played by Alan Alda says that “comedy equals tragedy plus time.”

It took a while—and there has been much tragedy—but God may finally be laughing at Mississippi. Something is happening in the land of cotton that has an ironic, even comic twist.

Soft-spoken Southern gentleman Lee Paris, 38, chairs the executive board of a new venture in Mississippi’s capital of Jackson, called Mission Mississippi (MM). The movement is spreading a remarkable impulse for reconciliation throughout the churches, businesses, and neighborhoods of the metropolitan area. Paris gets a laugh from Black audiences when he notes that he is “a White boy from the Mississippi Delta who went to an all-White private academy and Ole Miss.”

But, says Paris, “if reconciliation can be done in Mississippi, then having it done in other places should be a whole lot easier. The Lord is showing his sense of humor.”

In one week, two evangelical movements bent on reconciling the races gathered in Jackson. In the fullness of time plus tragedy, God has fashioned MM, which held its first major get-together. Similarly, God brought back home noted evangelical John Perkins, once tragically beaten in a Mississippi jail, now leading a group of older and wiser reconcilers, for its own celebration. The meeting in Jackson of Perkins’s Christian Community Development Association followed right on the heels of MM.

As I watched the two, myself a Mississippian wanting to deal with the issues at hand, I thought of the plaintive psalm, “Weeping may tarry for the night, but joy comes with the morning.” Having grown up in an affluent suburb of Jackson, having attended Ole Miss, a symbol for many of segregation and racism, I know about coming to gut-wrenching terms with what my state—even what I and some of my relatives—have done, or left undone.

On a cool October evening, I am watching a cross go up.

It is oversized and white, the sort that appears at many small-town church Easter pageants.

Yet this cross-raising is akin in epic motion to the famed scene on Iwo Jima: a mass of coated-and-tied men straining against their common history to raise a symbol of new life on Mississippi soil.

Black hands on white on black, they lift it. A spotlight makes it stand out vividly against the night.

Raised by dozens of Black and White Mississippi pastors before a crowd of some 7,000 Black and White onlookers in Jackson’s Mississippi Veterans Memorial Stadium, this cross symbolizes the heart of Mission Mississippi. Some say the group’s gathering (about 24,000 over three nights after one year of smaller, more intimate meetings in churches, high schools, and homes) was a future-shaping milestone for the state. They wonder if it might not have a national impact as well.

On one television special aired statewide, Randall Mooney, a White who has committed, along with his wife, to a relationship with a Black couple, Frederick and Wanda Pitts, said, “One of the biggest things we have to defeat with Mission Mississippi is the stigma that has been attached to Mississippi for racism. I am not saying that racism is not here. But the nation has put a magnifying glass on the state and said, ‘They are the ones that are racist.’ That’s why it’s so wonderful that God has decided, I believe, to choose that which is last to make it first.”

Paris will tell you quickly that Mission Mississippi is not primarily about improving his state’s reputation. “We aren’t doing it for the image, we are doing it for relationships.”

MM’s vision has grown from a gathering—unprecedented in this city—of a hundred Black and White pastors late last year. It is funded by more than 60 local churches and major state-based corporations, and it has been given free exposure by top television stations in the state. The governor declared October Mission Mississippi month, and Jackson’s mayor spoke at the MM gathering.

The movement ranges from top business executives to McDonald’s burger flippers. They are after the kind of reconciliation that leads people from different races to eat in each other’s houses and cry together on bent knees.

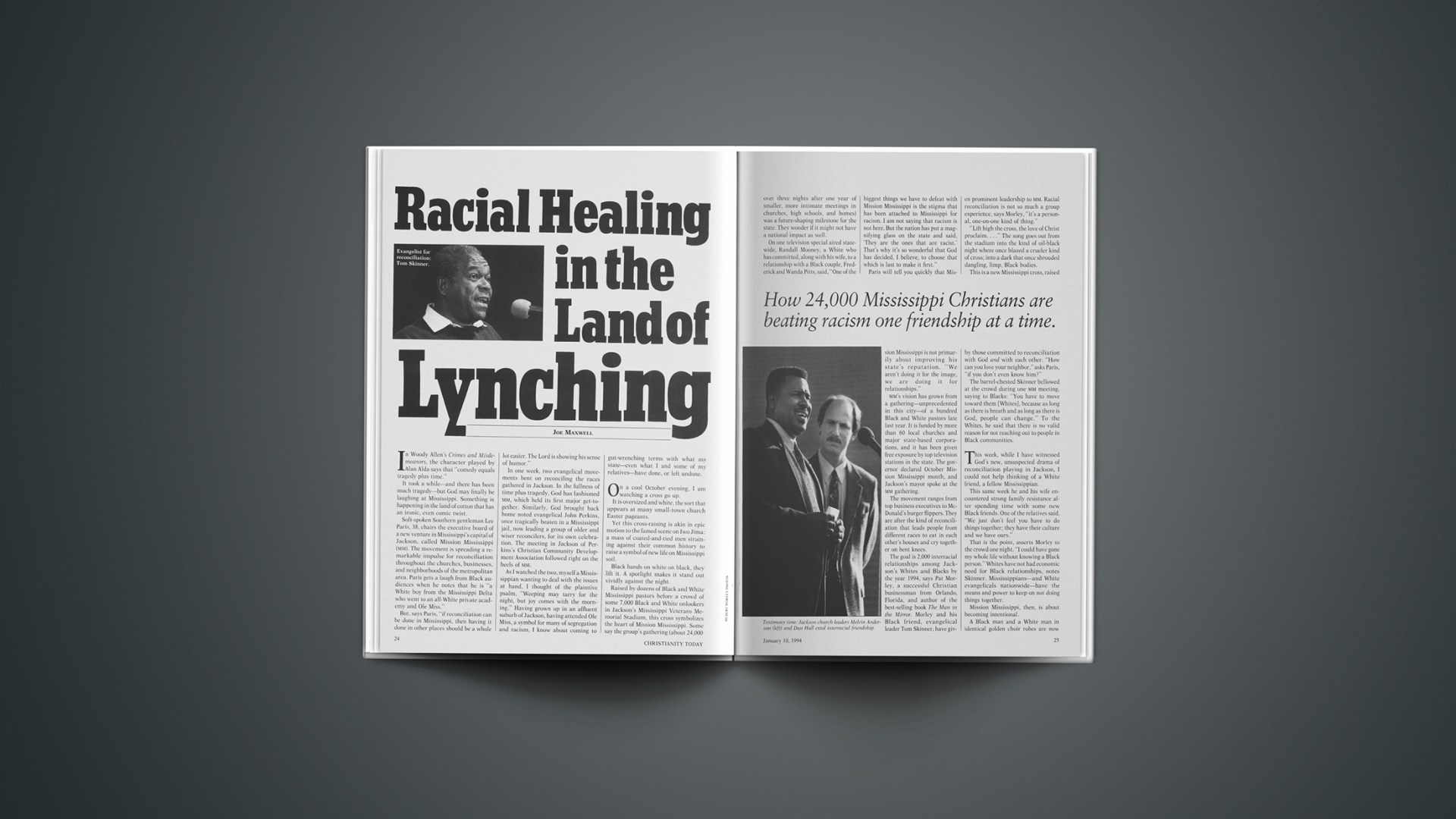

The goal is 2,000 interracial relationships among Jackson’s Whites and Blacks by the year 1994, says Pat Morley, a successful Christian businessman from Orlando, Florida, and author of the best-selling book The Man in the Mirror. Morley and his Black friend, evangelical leader Tom Skinner, have given prominent leadership to MM. Racial reconciliation is not so much a group experience, says Morley, “it’s a personal, one-on-one kind of thing.”

“Lift high the cross, the love of Christ proclaim.…” The song goes out from the stadium into the kind of oil-black night where once blazed a crueler kind of cross; into a dark that once shrouded dangling, limp, Black bodies.

This is a new Mississippi cross, raised by those committed to reconciliation with God and with each other. “How can you love your neighbor,” asks Paris, “if you don’t even know him?”

The barrel-chested Skinner bellowed at the crowd during one MM meeting, saying to Blacks: “You have to move toward them [Whites], because as long as there is breath and as long as there is God, people can change.” To the Whites, he said that there is no valid reason for not reaching out to people in Black communities.

This week, while I have witnessed God’s new, unsuspected drama of reconciliation playing in Jackson, I could not help thinking of a White friend, a fellow Mississippian.

This same week he and his wife encountered strong family resistance after spending time with some new Black friends. One of the relatives said, “We just don’t feel you have to do things together; they have their culture and we have ours.”

That is the point, asserts Morley to the crowd one night. “I could have gone my whole life without knowing a Black person.” Whites have not had economic need for Black relationships, notes Skinner. Mississippians—and White evangelicals nationwide—have the means and power to keep on not doing things together.

Mission Mississippi, then, is about becoming intentional.

A Black man and a White man in identical golden choir robes are now singing, backed by a Black and White choir: “United together, we’ve got the victory. Hallelujah!”

Stuart Kellogg is the manager of a television station based in Jackson. He is an evangelical, and he and I are watching the two men sing.

Kellogg has worked around the country, and he believes that “the divisions are less severe” in Mississippi. Why? “The sixties were so traumatic. Everyone else thought it was just the South’s problem and never dealt with it. In that sense, the South is ahead.” Whenever reconciliation is attempted, feeling the pain, sometimes traumatically, is a necessity. MM is about facing the pain better—about doing some weeping.

A few days before the three nights of MM rallies occurred, a group of Blacks and Whites gathered at a forum to talk. But not too far into their meeting, one younger Black pastor stood up and got down to the nitty gritty: “There have been nearly 700 lynchings in the state of Mississippi, but I have never heard a White pastor preach against racism, and I need to know—why?” There was a brief quiet around the room, and then a White pastor—one of the older ones—stood up. “I guess that question falls to me,” he said.

“To tell you the truth, it was fear. We were afraid: afraid of our people and of the consequences. So we just stood by.

“And the truth is, I don’t know how to make it right. I’d like to go back, but we can’t. All I can do is tell you I’m sorry; I’m sorry.”

Amidst his words, tears welled up in the eyes of both Blacks and Whites present as the two men embraced.

I am sitting in the Holiday Inn in downtown Jackson on Saturday, four days after MM wrapped up. The Christian Community Development Association (CCDA), a network of more than 180 churches and ministries across the nation committed to holistic community development, has come for its fifth-annual meeting to Jackson, where Black evangelical leader John Perkins in 1973 founded Voice of Calvary. It is also near where he founded the predecessor to Mendenhall Ministries in 1961; both remain working, milestone models of White-Black reconciliation. Perkins is the chairman of CCDA’s board.

I am having breakfast with a Black man who, as a Harlem gang leader, once loved to put his knife into people. He hated Whites. Across the room is a White man who, as a Mississippi Klansman, once nursed fantasies of blowing up Jews. He hated Blacks.

Today the two men love each other.

Tom Skinner, that Black man, is obviously tired from weeks of work here leading up to MM—and from preaching to the unconverted. Yet, instead of returning to his Maryland home, he stayed on so he could speak last night to a CCDA gathering of 1,200 Whites and Blacks. This was preaching to the choir!

“This is very significant,” says Skinner, as together we look out over a room of Whites and Blacks eating breakfast and talking about more than business.

The gathering’s significance does not escape even our waiter, Alvin, a Black 28-year-old. He is clearly impressed by a group of Blacks and Whites eating together and “looking at each other as humans, not as colors.”

But Melvin Anderson, 38, president of Voice of Calvary Ministries, would be the first to say that such relationships do not come easily.

Anderson was heavily involved with MM, and he and a White pastor over the last year have committed to a relationship of eating together, talking together, being together.

Yet Anderson is not new to this challenge, having been committed to the process since his childhood, when Perkins initially influenced him. So when MM finished this week, Anderson asked several of its top leaders to come with him two nights later to the first night of CCDA’s gathering. For Anderson, it was like inviting the men to a family reunion of sorts. “I said, ‘These are the people who have been living out what you are talking about.’ ”

Anderson continues reflecting as we sit in the large Holiday Inn meeting hall between the CCDA seminars. “This has been an amazing week. I’ve been thinking about what it was like when we first came to Jackson. Integration was just taking place. And now, here we are 23 years later. There is a different push from God. It is a different thing that people are being sewed together with today.”

It is this sort of gospel that 17 years ago caught up with Tom Tarrants, 47, the former KKK leader mentioned earlier. In a blue blazer and khaki slacks, Tarrants is eating a healthful salad, sipping coffee, and speaking in a soft voice; he is not slobbering over fried chicken and loud-mouthed, as one (such as I, I confess) might envision a former Klansman.

He admits that he used to be a fire breather decades ago. His involvement with the KKK became more militant as he moved to the White Knights, and he was in deadly gun fights with law officers twice after trying to blow up a Jewish man in Meridian, Mississippi. Now he pastors an evangelical church in Washington, D.C. “God changes us, you know,” he says with a smile.

Tarrants says he sees little hope for race relations in America short of Christ. “It is an issue of the lordship of Jesus Christ; it is not a sociological issue. Having said that, though, there is an outworking. That process for me has taken years as I’ve developed relationships with Black people.”

Looking around the room, I hear a Black man getting impatient with two White men. He is trying to convince them to fund his ministry, and by his body language and tone of voice, he must think they aren’t getting it. But they do seem to be trying.

That is a lot of what CCDA is about, it seems: commitment to the process and not bailing out.

Skinner says Mississippi’s efforts at race relations resemble a batter in baseball: the average hitter bats about .251; a good hitter bats about .280; “but anybody who wants to win the batting title wouldn’t settle for .280.”

Mississippians, he says, have a long way to go. They are proud and sometimes defensive, and “they find it very painful to own up to their past.”

As a White evangelical, I can’t help feeling that I may be doubly guilty. Not only are many of us Mississippians a proud and defensive bunch, so are many of us White evangelicals.

I am now at the Saturday evening CCDA meeting of a thousand or so. A choir of Blacks and Whites sings in the Yoruba language of western Nigeria. They are swaying, their faces like angels—free from façades and fury and fear. They are rejoicing.

“Ose Baba” (“Thank you, Father”), they sing. “Ose Baba.”

A shout of joy.

And after years of weeping over Mississippi, God, I believe, must finally be laughing.

Paul Brand is a world-renowned hand surgeon and leprosy specialist. Now in semiretirement, he serves as clinical professor emeritus, Department of Orthopedics, at the University of Washington and consults for the World Health Organization. His years of pioneering work among leprosy patients earned him many awards and honors.