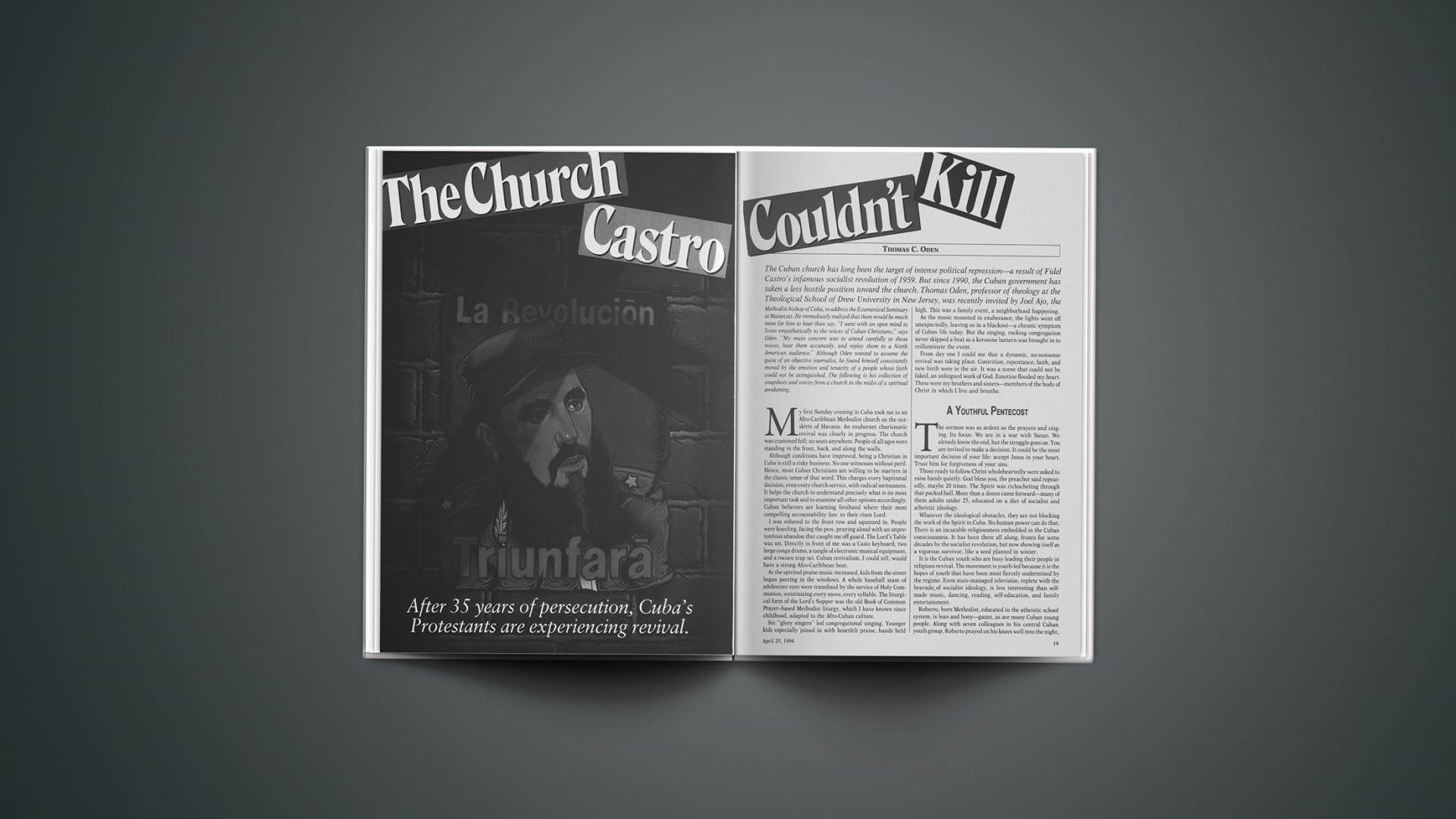

After 35 years of persecution, Cuba’s Protestants are experiencing revival.

The Cuban church has long been the target of intense political repression—a result of Fidel Castro’s infamous socialist revolution of 1959. But since 1990, the Cuban government has taken a less hostile position toward the church. Thomas Oden, professor of theology at the Theological School of Drew University in New Jersey, was recently invited by Joel Ajo, the Methodist bishop of Cuba, to address the Ecumenical Seminary at Matanzas. He immediately realized that there would be much more for him to hear than say. “I went with an open mind to listen empathetically to the voices of Cuban Christians,” says Oden. “My main concern was to attend carefully to those voices, hear them accurately, and replay them to a North American audience.” Although Oden wanted to assume the guise of an objective journalist, he found himself consistently moved by the emotion and tenacity of a people whose faith could not be extinguished. The following is his collection of snapshots and voices from a church in the midst of a spiritual awakening.

My first Sunday evening in Cuba took me to an Afro-Caribbean Methodist church on the outskirts of Havana. An exuberant charismatic revival was clearly in progress. The church was crammed full; no seats anywhere. People of all ages were standing in the front, back, and along the walls.

Although conditions have improved, being a Christian in Cuba is still a risky business. No one witnesses without peril. Hence, most Cuban Christians are willing to be martyrs in the classic sense of that word. This charges every baptismal decision, even every church service, with radical seriousness. It helps the church to understand precisely what is its most important task and to examine all other options accordingly. Cuban believers are learning firsthand where their most compelling accountability lies: to their risen Lord.

I was ushered to the front row and squeezed in. People were kneeling, facing the pew, praying aloud with an unpretentious abandon that caught me off guard. The Lord’s Table was set. Directly in front of me was a Casio keyboard, two large conga drums, a tangle of electronic musical equipment, and a rococo trap set. Cuban revivalism, I could tell, would have a strong Afro-Caribbean beat.

As the spirited praise music increased, kids from the street began peering in the windows. A whole baseball team of adolescent eyes were transfixed by the service of Holy Communion, scrutinizing every move, every syllable. The liturgical form of the Lord’s Supper was the old Book of Common Prayer-based Methodist liturgy, which I have known since childhood, adapted to the Afro-Cuban culture.

Six “glory singers” led congregational singing. Younger kids especially joined in with heartfelt praise, hands held high. This was a family event, a neighborhood happening.

As the music mounted in exuberance, the lights went off unexpectedly, leaving us in a blackout—a chronic symptom of Cuban life today. But the singing, rocking congregation never skipped a beat as a kerosene lantern was brought in to reilluminate the event.

From day one I could see that a dynamic, no-nonsense revival was taking place. Contrition, repentance, faith, and new birth were in the air. It was a scene that could not be faked, an unfeigned work of God. Emotion flooded my heart. These were my brothers and sisters—members of the body of Christ in which I live and breathe.

A YOUTHFUL PENTECOST

The sermon was as ardent as the prayers and singing. Its focus: We are in a war with Satan. We already know the end, but the struggle goes on. You are invited to make a decision. It could be the most important decision of your life: accept Jesus in your heart. Trust him for forgiveness of your sins.

Those ready to follow Christ wholeheartedly were asked to raise hands quietly. God bless you, the preacher said repeatedly, maybe 20 times. The Spirit was richocheting through that packed hall. More than a dozen came forward—many of them adults under 25, educated on a diet of socialist and atheistic ideology.

Whatever the ideological obstacles, they are not blocking the work of the Spirit in Cuba. No human power can do that. There is an incurable religiousness embedded in the Cuban consciousness. It has been there all along, frozen for some decades by the socialist revolution, but now showing itself as a vigorous survivor, like a seed planted in winter.

It is the Cuban youth who are busy leading their people in religious revival. The movement is youth-led because it is the hopes of youth that have been most fiercely undermined by the regime. Even state-managed television, replete with the bravado of socialist ideology, is less interesting than self-made music, dancing, reading, self-education, and family entertainment.

Roberto, born Methodist, educated in the atheistic school system, is lean and bony—gaunt, as are many Cuban young people. Along with seven colleagues in his central Cuban youth group, Roberto prayed on his knees well into the night, seeking the baptism of the Holy Spirit.

“At first we were a little afraid of it. Then we said together, as with one voice, to God: ‘We are going to remain on our knees until you baptize us with your Spirit.’ I was like Jacob wrestling with the angel, pleading: ‘I am not going to let go of you until you reveal yourself.’

“That night, when our pastor discovered that we were searching for this experience, he chided us, saying that nothing was going to happen, that we were wasting our time. But when he saw that some of us were receiving the gifts of the Spirit, he then joined in with us in our prayer vigil. Soon the pastor was asking the Spirit to anoint him as well. That night was the start of a ministry of the gifts of the Spirit: of discernment, of love, of understanding, and even of healing.”

As the young man spoke, my mind could not help turning to Acts 2: Were the events of Pentecost being replayed in the churches of this troubled republic?

Roberto beamed as he informed me that his youth group has 128 kids, and that 50 people would be joining his church the following Sunday. His faith was contagious.

CHOOSING LIFE

The only entrée for Americans to Cuba is by invitation. This has resulted in a long train of liberal ecclesial sycophants traveling to Cuba to pay homage to Castro and condemn American policy. When my invitation came out of the blue from Methodist Bishop Joel Ajo, I was glad to learn that this sort of quasi-political game-playing was no longer necessary.

With the revolution came an influx of leftist philosophies to the church. Prior to Castro’s regime, Protestant missions in Cuba were shaped by Anglican evangelicals, Reformed individualists, and Wesleyan revivalists. The majority of lay Cuban Christians remain basically conservative evangelicals. Yet the only link, ironically, between these lay congregations and the North American Christian laity has been through an ultra-liberal church bureaucracy whose liberation-theology rhetoric now sounds passé to Cuban ears.

Staying its course amid the ideological fog has been the Methodist Church of Cuba, an autonomous church that has been evolving with practically no help from the outside world for more than 30 years. This has freed the church to rediscover its own distinctive Caribbean evangelical identity, and now it is growing profusely. Once down to 6,000 members, Cuban Methodism now numbers over 50,000. One local church in central Cuba has 26 house churches averaging over 50 persons per home.

Cuba’s house-church movement is a prime example of the explosive growth taking place among evangelical believers. Born out of the repressive policies of the revolution, house churches evolved as Christians spontaneously began inviting people to their homes for prayer, hymn singing, and Bible study. As with the early Christian church, the threat of persecution became an impetus for expansion.

One thing is certain: in a crisis of life or death, Cuban evangelicals have chosen life—the life lived through the power of the Spirit.

SEARCHING FOR MEANING AND BREAD

Daytime in Cuba. The air in the city streets is tinted purple, dusted by diesel smoke. Unmuffled motor noises deafen ears and drown nearby human voices. Cars whiz down narrow streets, barely missing dogs and pedestrians.

I recall the surreal image of a wiry man on a bicycle carrying a large, unwieldy oil dram on his back, with the bike creaking and groaning beneath. There was a lot of movement on the street, more trucks than cars, and much more walking or cycling than driving. The streets were dotted with droppings from mules and horses pulling carts and carriages.

Economically, Cuba is running on empty. The fall of the Soviet Union spelled an end to the country’s main supply of oil, grain, and other essential resources.

I saw long lines of people in the city square waiting for breakfast. They had pesos, but there is little food available, even if you have the money.

As I strolled about the urban center of the provincial capital of Matanzas, I realized that the people are doing more with less than I have been accustomed to seeing. I was transported back to my depression-era boyhood in Oklahoma. We never thought of ourselves as poor, even though our state was as hard hit as any by the Great Depression. That is the way Cuba seems today. People have learned to get by, to invent. I remember making toys out of wood and tinfoil, spending hours collecting stamps and making model airplanes, never throwing anything away, and finding meaning in the simplest activities. The Cuban people exhibit that same kind of creativity shaped by limitation.

There are three types of Cuban Christian voices: prerevolutionary, revolutionary, and postrevolutionary. The prerevolutionary voices dream of turning the clock back to before 1959. The revolutionary voices still dream of making the socialist revolution work. But most of the voices I heard were postrevolutionary. Pablo is a good example.

Pablo is a young, brawny, athletic, blue-collar worker—a Protestant and father of two. As he cleaned out a carburetor, we talked about being a Christian in Cuba.

“For many years the people in Cuba turned their backs on God,” he explained as he tightened a bolt. “Now in this economic crisis, the Lord is showing us that he is accompanying the people despite their faithlessness.

“The restrictions that once prohibited Christians from joining the Communist party have now been overturned. The unexpected flip-flop is that there is a noticeable movement of old Communists back toward the church. Just as the government was deciding generously to permit Christians to become party members, the party members were beginning to abandon the party to join the church. They come out of hunger for meaning. One party member, after being baptized, returned her party identity card. She did not want it. Many young people have returned their party cards.

“Yes, there has been some indirect persecution of Christians for their beliefs, although the official reason given for arrests has always been the breaking of some other law. That harassment mentality is gradually being turned around. Before 1990, people would decide regretfully not to attend church for fear of losing out on a university education or preferred career.

“Now being a Christian no longer carries such a heavy onus. During the height of the revolution, the society did not look well upon the church. Even though the socialist establishment bureaucrats felt in their hearts a need for God, they worshiped God only in veiled ways. Today spiritual concerns rank above all political concerns among our young people. They are bored with political rhetoric.

“The search for meaning is just as crucial as the search for bread. While the economy around us is falling apart, Christians are living in a state of special grace. It is not difficult for Cubans to see the difference between the people of God and those who are desperately trying to live without faith. Ordinary Cubans are becoming aware of the church as a lifesaving community of hope.”

Pablo stepped away from his car and wiped his hands on a ragged handkerchief before reaching for a cup of water. His eloquence somehow seemed out of place there over a greasy carburetor. I asked him if there was some particular incident when his consciousness shifted drastically, when he clearly recognized that God was doing a special work in Cuba.

“I was already a Christian when this happened. Before this change, I could not conceive of an open, candid dialogue between the church and this regime. I could not conceive of the church as having a voice of its own or acting without the consent of the state.

“I found it incredible to see the confrontation between Bishop Joel Ajo and Fidel. Everyone in Cuba saw it on live TV on April 4, 1991. All the Protestant leaders had been called into a dialogue with Fidel. All these leaders were giving ‘yes, sir’ obeisance to Fidel except Bishop Ajo. Everyone was adulating Fidel, saying they were not going to ask him for anything. Then Ajo stood up and said: ‘I want to ask you to pay a debt that is over 30 years old.’

“After that, everyone was talking about what kind of guy would stand up and challenge Fidel publicly. Joel talked with him as if he were a friend. To Fidel’s face he pointed out that the Cuban-based churches were not permitted to have access to radio programming, but Cubans were able to pick up broadcasts from other countries. ‘Why do you allow radio programs from other countries, but not from Cubans themselves who have cast their lot with the Cuban people?’ Fidel said: ‘We will talk about that.’ Joel insisted that Fidel owed a debt to the churches: to restore their freedom. I knew then that God was opening new doors.”

REMYTHOLOGIZING CUBA

In a recent interview, Castro stated that it was never his intent to have a breach between the church and the revolution. That only happened, he said, because of the people surrounding him, not because of his own initiative. Many of those I surveyed begged to differ.

In an obligatory pilgrimage to the Museum of the Revolution, I saw history being blatantly remythologized.

Faded newspaper clippings proclaimed the glories of the revolution. I was at once struck by the idolatry of guns, arms, and other devices of war in that gallery of the revolution, each pistol sentimentally exhibited. Clearly, the entire museum is dedicated monomaniacally to a single hero, with his warped dream of absolute equality.

Castro’s reshaping of Cuban history looks to a theologian like a revised glossary of the order of salvation. Instead of an Adamic fall, redemption in Christ, and sanctification through the work of the Spirit, the order of salvation mimics Marxist-Leninist dogma: The innocent and productive aborigines fell into the clutches of inefficient, coercive colonial capitalism, but then came the savior whose name was Fidel. Instantly evil was overcome, and the new society is now going on to perfection. This romantic scenario of national salvation is really a bastardized version of the Christian view of history.

There is a mystique that pervades the official version of the revolution. It has its own saints and devils, its own hagiography. Cuba’s Christian history is demonized. Here history is being rewritten, from end to beginning.

If this museum is ever to become a sightseeing spot—which is the fond hope of the Cuban tourism office—something will have to be done to make it less laughable. For instance, to raise a serious question in this solemn environment would be like passing wind in a library. There is under this roof no tolerance for inquiry, and no thought of the possibility of free inquiry.

Across from the Museum of the Revolution stands the gleaming white Church of the Holy Protector, which contains a stunning statue portraying the dead Lord of glory covered by a shroud of delicate netting. The lines of his lifeless face are visible through gauze graveclothes. I could not help pondering the irony of this poignant rendition of the death of God, poised for resurrection, so like the church of Cuba.

LIBERATED FROM LIBERATION

A calm, serene, verdant vista enfolds one of the deepest harbors in Cuba: Mantanzas. My eye was drawn toward the ornate twin domes of a church where the rivers meet and touch the sea. On this holy hill stands the Seminario Evangélico de Teológico. I would soon have the privilege of addressing its students.

Reminders of the 1959 revolution abound: An ancient 1958 Chevy with no headlights rests in peace outside the faculty offices. A 1953 Dodge without wheels rests on blocks nearby.

There is something dying in that valley below the seminary. What is it? A system. An economy. A dream. A rhetoric. Yes, a revolution. In a distant dump site, I observed fragments of old revolutionary posters now shredded and mildewing. But the seminary remains standing amid this collapse of ambitious human schemes—a testimony to the mighty God who never left.

The seventies were the decade of crisis for the seminary. As I strolled the palm-lined seminary campus with an elderly professor I will call “Francisco,” I heard the history rehearsed: How the number of students during the revolution’s peak had diminished so that it equaled the number of professors. How the plant and installations were left unrepaired. How the Methodists no longer sent students. How the laity were afraid that if they sent pastors there, they would become so politicized as to become useless to churches.

At its lowest point, the seminary had only six students. The prevailing school of thought—liberation theology—accommodated Marxist rhetoric. Cuba’s major liberation theologian was the seminary rector, Sergio Arce, key author of the Marx-mimicking Confession of Faith of 1977, which declared commitment to Cuba’s communist revolution as “part of the creative, redemptive, and reconciling activity of God in the world,” and a matter of confessional faith (status confessionis) for Cuba’s Presbyterian-Reformed Church. Proletarian workers were conceded to be “the legitimate standard-bearers of the new order.” Sin and salvation were described almost exclusively in political and economic terms; Jesus was interpreted as the prototype of one who “took the side of the oppressed and exploited class.” The kingdom of God was in those days viewed as inextricably tied to “the class struggle that is manifested in the Bible in the contradiction between oppressors and oppressed.” It is from this pit that the seminary has gradually risen to a solid, more orthodox ground.

The seminary is now being led by a Methodist pastor and former district superintendent who is revitalizing the spiritual formation of the students. Under his guidance has come a shift toward pastoral identity in the curriculum, seeking to “join the two so long divided, knowledge and vital piety.”

During my stay at the seminary, Francisco invited me to his home one morning to chat over prebreakfast coffee.

A cartoon of Donald Duck whacking a baseball was on the door of the old man’s apartment—a single spare room that reminded me of a monastic cell. Three walls were filled with books on hermeneutics, psychology, and biblical studies. There was a tidy, unadorned bed and a few heating pots.

An ever gracious host, Francisco brought out some bread to complement our potent brew of Cuban coffee. The bread was dry and hard, he explained, but still good.

After I had eaten my breakfast bread, he broke his in half and put it in front of me, remarking with a knowing glance: “I don’t want you to go back to America and say you were hungry in Cuba.”

Between bites of my bread, I asked him questions about the present and future state of the Cuban church.

“We are right now in a situation of sheer daily survival. It is dangerous, challenging, and absorbing. The system itself is trying to survive. The vocation of the church is to show that it has the moral and spiritual strength to be of some tangible, useful help in this survival situation.

“To be a Christian amid a struggling socialist system is a wonderful adventure. Here you can discover that the promises of God belong to you. You grasp this only when you rely under risky conditions upon those promises. They are best proved true for the faithful in difficult, challenging situations. Here the church must truly be the church or its identity will quickly be lost.”

Francisco paused briefly to sip from his coffee. I could tell I had tapped the preacher in him. “The Jeremiah narrative is especially instructive for us in Cuba. The Lord addresses Jeremiah in jail: ‘Call to me and I will answer you, and will tell you great and hidden things which you have not known’ [Jer. 33:3]. The Bible does not say, ‘Call to me and I will make you free.’ The Hebrew says I will show you not just magnificent things, but difficult and mysterious and inaccessible things, things otherwise out of reach to your slender imagination. Jeremiah has helped Cubans choose to be survivors amid this situation. This is a verse that we would do well to focus on in the coming years.”

SAVORY SALT

Today, I sit at home in Jersey, far away from the peculiar sights and odors of my Caribbean journey. But the spirited and profound voices of my Cuban brothers and sisters continue to play in my mind and heart. I know now that what I experienced was not just a church regaining vision in an ailing socialist regime; what I experienced was a firsthand view of the power and triumph of the Living God over the chains of the Enemy.

For 35 years, Cuba was the only state in the Western Hemisphere where the government was openly atheistic and determined to erase Christianity. But, despite intense police repression, this attempt has been singularly unsuccessful.

No one knows what the political future might be. Any partisan gesture could easily end up on the wrong side. What the church is sure of is that it will continue to accompany the ordinary Cuban people into whatever circumstances or along whatever trajectory they are hurled.

My insightful friend, Francisco, feels the church has the only solution to the republic’s ills: “Cuba is not yet fully ready to hope, but the Cuban church must take responsibility of offering hope where there is none. Hope, as Abraham and Kierkegaard knew, is a passion for the possible. The Cuban church has that passion. It is the salt that has not lost its savor.”

Paul Brand is a world-renowned hand surgeon and leprosy specialist. Now in semiretirement, he serves as clinical professor emeritus, Department of Orthopedics, at the University of Washington and consults for the World Health Organization. His years of pioneering work among leprosy patients earned him many awards and honors.