John Chrysostom is remembered by Western Christians (if he is remembered) mostly as a great preacher. But to 215 million Orthodox believers, John is much more. To discover why, Christian History talked to Bishop Kallistos Ware, lecturer in Eastern Orthodox studies at the University of Oxford. Bishop Ware is author of two popular introductions: The Orthodox Church (Penguin, 1963), and The Orthodox Way (Mowbray, 1979).

Christian History:

Why is John Chrysostom so well remembered by Eastern Orthodox Christians today?

Kallistos Ware:

He is familiar to every Orthodox believer because we hear his name each Sunday in worship. The liturgy celebrated nearly every week is attributed to St. John Chrysostom. At the end of the service, in the final blessing, we hear the words, ” … the prayers of our holy father, John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople, whose liturgy we have celebrated.”

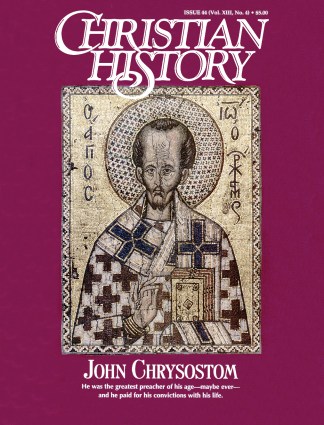

In addition, we see him in church: his icon, along with others, is displayed at the front of the church. He is pictured in bishop’s vestments, standing with head bowed, holding a scroll of the divine liturgy associated with his name.

Did John actually write this service?

The service has been evolving from before John, but the nucleus of it likely goes back to Chrysostom’s time. The service at Antioch that John used contained at least some of the elements we use today.

What is unique about John’s understanding of worship?

John bequeathed a very strong sense of the unity between the worship of the earthly congregation and the worship that goes on unceasingly in heaven. “When the priest invokes the Holy Spirit,” he once said, “angels attend him, and the whole sanctuary is thronged with heavenly power.” Put simply, John thought of worship as “heaven on earth.”

When we celebrate the Eucharist, John explained, we are taken up into an action much greater than ourselves: “When you see the Lord’s sacrifice lying before you … and all who partake marked with the precious blood, can you imagine that you are still among humans and still standing on earth? Are you not at once transported to heaven? Do you not gaze around upon heavenly things?”

We’re surprised that you didn’t mention preaching as the first thing you appreciate about John.

His preaching is, naturally, central, yet the sermon for John was part of the liturgy. Chrysostom was a liturgical preacher. His sermons were normally delivered during the divine liturgy.

What to you is most impressive about John’s preaching?

His deep love for holy Scripture. He can be truly called an evangelical. He likes to keep close to the literal sense of the Scripture.

Another thing is John’s emphasis on love for others. In one sense, we cannot be saved without others: our sanctification is found in them and theirs in us as we love and serve one another. That’s the main way we “work out our salvation” (Phil. 2:12).

Is this why John was so concerned about the poor?

Partly, but this also is connected with his view of worship. Worship as heaven on earth goes hand in hand with a strong social conscience. “You honor the altar at church, because the body of Christ rests upon it,” he once said, “but those who are themselves the very body of Christ you treat with contempt and you remain indifferent when you see them perishing.” Upon this living altar—which can be seen lying in the streets and the marketplaces, he said—one can also offer a sacrifice to God.

The body of Christ received in the sacrament is vital, but there’s also the living body of Christ, which to Chrysostom means all human beings. Not that everyone is saved and a member of the church. But every human being, made in the image of God, reflects the image of Christ. Christ himself, in fact, identified himself specifically with the poor and needy (Matt. 25).

Every evening in London’s center, you can see homeless people sleeping in the streets, in cardboard boxes or under ragged blankets. That would have appalled Chrysostom. He would say there is something wrong with a society in which some people have grown rich while the poor lie homeless in the streets.

“The Unknowability of God” is one of John’s most famous treatises. Why was that seemingly abstract theme so important to John?

John felt deeply that God is a mystery beyond our understanding. We cannot understand God in the way he understands himself. If we did, we would be God!

John believed in God’s nearness—that God reveals himself, that we share in his grace and glory. But God always remains the One who is beyond and above all that we know. He is closer to us than is our own heart, and yet he is beyond and above everything. This has been a strong emphasis of Eastern Orthodoxy through the centuries.

What difference has that emphasis made?

It means, first of all, that we haven’t set too high a value on human reason. Human reason is a gift from God, and we must use our reasoning powers to the full. But we cannot comprehend God through the use of syllogisms, analogies, or comparisons. Though we have a long tradition of theological reflection, we’ve never tried to make God fit our reasoning powers.

Above reason lies a higher faculty of spiritual understanding—the nous: our power to apprehend spiritual truth directly, immediately, intuitively, not just through reason but through inner vision.

This goes hand in hand with an emphasis on silence. St. Basil says, “Let things ineffable be honored with silence.” We mustn’t imagine that everything can be expressed in words. To learn to be silent is extremely difficult, but even in our most eloquent speeches, there has to be woven into them the dimension of silence. I think that happens in Chrysostom. He was a preacher of outstanding eloquence, but he never imagined that all truth could be put into words.

The mystery of God means a willingness to wait on God in inner stillness, not to verbalize everything. It’s an attitude of listening, of attending to Another. That’s surely very relevant for us today. We’ve driven silence out of our lives, and we need to recover it. I believe we are deeply sick as a society and as individuals because of our lack of silence.

Most Western Christians are unaware of John’s exile and death. Why are they important to you?

John had the courage of his convictions; he did not compromise the demands of the gospel to please those with wealth and power. As a result, he suffered, but he bore his sufferings with joy.

However, we do not limit his sufferings to his exile and death. In his youth, Chrysostom was a monk, and he lived a severely ascetic life. He practiced the ascetic life at home until he was able to go into the desert for a short time. In fact, he followed the ascetic life with such severity that he permanently damaged his health, which he later regretted.

In his early monastic training, he was a martyr inwardly—he died daily to the flesh through his ascetic practices. This helped prepare him for the time when he had to suffer outwardly as a martyr.

His end in 407 was hastened by the harsh treatment he received and the travel demands made on him. However, his last words are so well remembered, they’ve become a cliche: “Glory be to God forever” (some translate it, “Glory to God in all things”). But he said them with entire sincerity.

What most inspires you about John?

That he combines the role of liturgist and social reformer. John was deeply concerned with the worship of God, that worship should be done with beauty—but not at the expense of his social conscience.

In John, a concern for the church as heaven on earth goes hand in hand with the concern for serving the poor in specific and practical ways. His social action is a continuation of the liturgy.

Copyright © 1994 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.