In this series

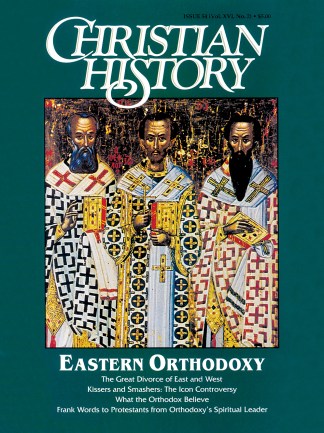

For many in the West today, Orthodox devotion to icons seems odd, especially the practice of kissing them. And when we learn that for a hundred-plus years in the early Middle Ages arguments raged over pictures of Jesus, causing one of the greatest political, cultural and religious upheavals in Christian History—well, we just don’t understand it.

What is it about icons that created such a stir, and what do they represent to the Orthodox?

A little bloody history

By the 700s, icons were a regular feature of Orthodox spiritual life all over the Byzantine Empire. And it was about that time that a movement against icons emerged. Iconoclasm (the movement to “smash icons”) started from within the church itself. A few iconoclastic bishops in Asia Minor (modern Turkey) believed the Bible, particularly Exodus 20:4, forbade such images:

“You shall not make for yourself an idol in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below. You shall not bow down to them or worship them . …”

Byzantine Emperor Leo III (reigned 717-741), convinced by such reasoning, tried at first to persuade his subjects to abandon icons. A dramatic act of nature reinforced his campaign: a violent underwater volcano suddenly erupted in the Aegean Sea; tidal waves surged over land, and a cloud of volcanic ash darkened the sky. The entire city of Constantinople was shaken. Leo interpreted it as a sign from heaven: the empire was in grave danger of incurring the divine wrath. So he preached a series of sermons against the use of icons.

In 726 (or 731; the date is uncertain), Leo stepped up the campaign. He ordered his soldiers to go to the palace gate called Chalke and destroy the icon of Christ painted over the entrance archway. When the soldiers began smashing the image, a group of elderly women kicked the ladder out from underneath the soldiers’ feet. The incident triggered riots, and several women became the first martyrs to iconoclasm.

The most vigorous opponent of icons in the eighth and ninth centuries was Emperor Leo’s son and successor, the brilliant Constantine V. Constantine was the person most responsible for developing the arguments used against icons.

In 754 he called the Council of Hieria, and the 338 bishops assembled from throughout the empire, condemned the making and venerating of icons. The deck, however, had been stacked: Constantine had guided into the assembly only those bishops who supported his views. Nonetheless, the bishops declared their assembly the “Seventh Ecumenical Council.”

After the council, a large-scale war broke out against the supporters of icons. Monks, icons’ staunchest defenders, felt the heat of persecution the most. Thousands were exiled, tortured, or martyred. In 766 Constantine paraded a group of monks holding hands with their sister nuns (a scandalous display) through the Hippodrome. Between 762 and 775, countless Christians suffered greatly, and the period became known as the “decade of blood.”

Eventually the tide turned. In 787 Empress Irene (reigned 780-802), a staunch supporter of icon veneration, convened what would later be recognized as the rightful Seventh Ecumenical Council. The council affirmed that icons, though they may not be worshiped, may be honored.

A new attack on icons was made under Leo V the Armenian in 815 and continued until 843, when icons were again reinstated once and for all by Empress Theodora on the First Sunday of Lent, a day still celebrated annually as the Feast of the Triumph of Orthodoxy.

God cannot be painted

The iconoclasts vehemently opposed icons for three basic reasons.

- Icons are idols. Emperor Constantine V argued, “The icon of Christ and Christ himself do not differ from each other in essence,” thus, “[An icon] is identical in essence with that which it portrays.” Since an icon cannot obviously be Christ in the flesh, it must be a false image—an idol. The Eucharist, iconoclasts further argued, was the only true image of Christ since that was the vehicle that contained Christ’s real presence. “The bread which we receive,” Constantine maintained, “is an icon of his body.” Yet, as the iconodules (icon supporters) argued, did not the Incarnation make a difference in the way Exodus 20:4 applied to icons? The iconoclasts declared “No!” The command against making images applied equally to Jews and Christians. Furthermore, there should be no portrayals of Mary, the saints, or angels. As the Council of 754 stated, “Since the former [an icon of Christ] has been abolished, there is no need for the latter either.”

- Icons are not supported by church tradition. The iconoclasts backed up their arguments with references from church fathers such as Origen, Eusebius, and Epiphanius of Salamis.

- Icons deny the church’s teaching about Christ. Starting with the Chalcedon Definition (451), iconoclasts maintained that Christ’s divine nature cannot be “circumscribed” (i.e., captured, limited) in a portrait. It is impossible to portray true divinity in an icon. Yet to say that icons portray only Christ’s humanity is to fall into another heresy—the belief that Jesus’ divine and human natures were not really united but juxtaposed.

The Word became “icon”

Three leading iconodule theologians finally united Orthodox opinion about icons: John of Damascus (c. 655-749), Theodore of Studios (759-826), and Nicephorus of Constantinople (758-828). Their threefold response went as follows.

- Icons are not idols. The iconodules defined icon differently than did their opponents. There is a vital difference between an image and its prototype, John of Damascus explained: “An image is a likeness, a model, or a figure of something, showing in itself what it depicts. An image is not always like its prototype in every way. For the image is one thing and the thing depicted is another.” Icons are not primarily historical but spiritual portrayals. An icon of the Resurrection, in which Adam and Eve are rescued from the grave, is not intended to paint an exact physical likeness of Adam and Eve. Rather the icon seeks to communicate spiritual and theological truths about the Resurrection: all of us sinners, like Adam and Eve, share in Christ’s victory over the grave. There is a difference, then, between an icon and the Eucharistic bread and wine, argued the iconodules: the Eucharist is not an image but Christ’s real presence. An icon is more like the Bible. A Bible is not “identical in essence” with the living Word, Jesus Christ, yet the Bible mediates the grace of Christ as we read it. Furthermore, the Seventh Ecumenical Council declared that the commandment prohibiting idolatry was designed to forbid Israelites from worshiping the false gods of the people they were about to conquer. Other scriptural texts suggest limited use of images (e.g., Exod. 25:18, 20; 36:8, 35; 1 Kings 6:28-29). Christian icons do not depict pagan gods; they are rather images that draw the venerator’s mind and heart toward the one true God as revealed in Jesus Christ.

- Tradition supports icons. The iconodules quoted church fathers like Athanasius, Basil, and John Chrysostom, who supported the use of icons. Furthermore, icon veneration had long been part of the practice of the most ancient churches, and none of the preceding six ecumenical councils had ever raised questions concerning it.

- Icons affirm the church’s teaching about Christ. Using texts such as John 1:14, Philippians 2:5-11, 2 Corinthians 4:4, and others, the iconodules argued that through the Incarnation, God identified wholly with the entire created order. Christ’s redemption extends to both the “spiritual” and “physical” sides of creation. If Christ did not have a real human body, then he didn’t identify completely with the created order. To deny an icon was to deny the Incarnation, a heresy! Like their opponents, the iconodules also drew their conclusions from the Chalcedon Definition. Icons are pledges of not only the Incarnation but also of the doctrines of deified humanity and the future transformation of the cosmos.

Honor and reverence

As for the role of icons in worship, the Seventh Ecumenical Council made an important distinction between veneration and worship: “We declare that one may render to icons the veneration of honor (proskune-sis), not true worship (latreia) of our faith, which is due only to the divine nature.”

Latreia means “absolute worship,” which is to be reserved exclusively for God. Proskunesis refers to the bodily act of bowing down and means “relative honor” that is offered to saints worthy of honor. Hence the physical act of bowing down to an icon and kissing it is not inherently idolatrous but a legitimate, cultural expression of respect.

In this way, the Seventh Ecumenical Council affirmed, “The honor paid to the icon is conveyed to its prototype.” When the Christian worshiper reverenced an icon of Mary or the saints, the honor was transferred to the person it represented. When an icon of Christ was reverenced, however, the worshiper could express not just veneration but absolute worship as well. For the one who was portrayed was none other than the God who became human.

John of Damascus summed it up best: “In former times, God, who is without form or body, could never be depicted. But now when God is seen in the flesh conversing with men, I make an image of the God whom I see. I do not worship matter; I worship the Creator of matter who became matter for my sake.”

Bradley Nassif is professor of biblical and theological studies at North Park University, Chicago, and an editorial adviser for Christian History.

Copyright © 1997 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.