In 987, Prince Vladimir of Kiev is said to have sent emissaries to different countries to learn about the religion and worship of each. He was searching for an appropriate faith for his people.

The emissaries went first to the Volga Bulgars. These Muslims they reportedly found disgraceful, sorrowful, and having a “dreadful stench.” And among the Germans (Western Christians), the ambassadors reported they saw “no glory.” In Constantinople, they were taken to Hagia Sophia, the cathedral church of the capital. Their report:

“We knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth. For on earth there is no such splendor or such beauty, and we are at a loss how to describe it. We know only that God dwells there among men, and their service is fairer than the ceremonies of other nations. For we cannot forget that beauty.”

Prince Vladimir was convinced, and his subjects accepted Greek Christianity and were baptized.

This account from the Russian Primary Chronicle, though legendary, nonetheless conveys this: the Russians were converted not by theological arguments but by the sheer splendor of Byzantine worship.

This liturgical tradition, followed even in the most remote parish, more than anything else still defines Orthodoxy. A brief “tour” of an Orthodox service will help the non-Orthodox grasp this truth more deeply.

The dance of worship

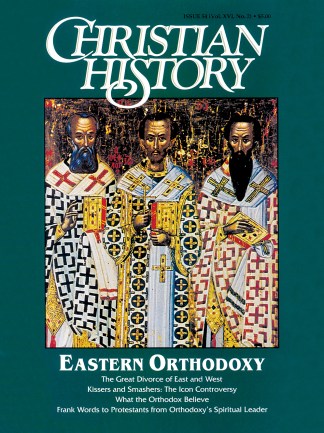

A western visitor to an Orthodox church is immediately struck by the building. Icons of saints and biblical scenes cover the walls and ceiling, sometimes entirely. A screen covered with icons, called the iconostasis, separates the sanctuary (where the altar sits) from the nave (where the congregation gathers).

Over the nave soars a large central dome, from which an austere image of the Pantocrator (Christ seated on his throne of glory) gazes down on the gathered assembly. Images of Christ and the Theotokos (Mary, “Birthgiver of God,”) flank the central doors of the iconostasis.

The images are large, bold, formal, lacking any sentimentality. They intend to convey this: you stand in the presence of the living God, together with the saints and the righteous of every age. Before a single word has been uttered, then, the congregation forms itself into a mirror image of the heavenly assembly of all believers, who together sing, “Holy, Holy, Holy … ” (Rev. 4:8).

As the service begins, the visitor is transported into a new and unfamiliar world. The smell of incense fills the church. The central doors of the iconostasis are opened and the priest, vested in resplendent robes, intones the opening benediction. The deacon chants the opening litany, and the choir and people respond, Kyrie eleison (“Lord, have mercy”). Nearly the entire service is chanted or sung.

At each petition, the people make the sign of the cross and bow, offering their prayers physically, as well as mentally. They stand throughout the long service, as Orthodox churches generally lack pews.

The clergy move in and out of the sanctuary in what appears to be a precise dance. Acolytes process with candles. Singers juggle the numerous music and hymn books. The faithful move back and forth, placing candles on stands before icons.

All this appears to be complex and chaotic, but to the worshipers it is all natural. Everyone knows his or her role in the assembly.

The visitor is also struck by the hymns and prayers. Some are chanted aloud for all to hear, others recited almost inaudibly. Westerners, accustomed to brief, simple, direct prayers, are often taken aback by the elaborate, flowery, and highly poetic language of the Byzantine liturgy. These texts, most composed between the fourth to the eleventh centuries, represent the highest achievement of medieval Greek Christian culture.

Prayers and hymns are largely built on scriptural material. The eucharistic prayer composed by St. Basil the Great, for example, contains at least 44 direct biblical citations in the preface alone.

The kingdom comes

Long before printed books, universities, or seminaries, this liturgy educated and formed the faithful. Scripture is read and expounded upon, hymns convey church teaching, and icons corroborate that teaching. A peasant in the Carpathian Mountains of Ukraine who may never have heard of the Council of Chalcedon (451), which affirmed the two natures of Christ, will know from memory an Orthodox hymn paraphrasing its decrees.

This liturgical tradition has developed continuously, yet in all ages, Orthodox worship has sought to offer the faithful a unique vision and experience. The Orthodox believe that, through the Holy Spirit, Christ descends to give us his Word and his body and blood. At the same time, we are transported to where he is, so that every time the church gathers for worship, we experience a foretaste of the kingdom.

Paul Meyendorff is professor of liturgical theology at St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary, Crestwood, New York.

Copyright © 1997 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.