In the fall of 1987, Phillip Johnson, a middle-aged law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, began a sabbatical year in England. His distinguished academic career had specialized in criminal law and lately branched out into more philosophical fields of legal theory. Nevertheless, Johnson could not shake the feeling that his life amounted to a wasted talent, that he had used a first-class mind for only second-class occupations. He was “looking for something to do the rest of his life” and talked about it with his wife, Kathie, as they hiked around the green fields of England: “I pray for an insight,” he told her. “I’d like to have an insight that is worthwhile, and not just be an academic who writes papers and spins words.”

In London, Johnson’s daily path from the bus stop to his office at University College took him by a scientific bookstore. “Like a lot of people,” Johnson says, “I couldn’t go by a bookstore without going in and fondling a few things.” The very first time he walked by he saw and purchased the powerful, uncompromising argument for Darwinian evolution by Richard Dawkins, The Blind Watchmaker. Johnson devoured it and then another book, Michael Denton’s Evolution: A Theory in Crisis. “I read these books, and I guess almost immediately I thought, This is it. This is where it all comes down to, the understanding of creation.”

Johnson began a furious reading program, absorbing the literature on Darwinian evolution. Within a few weeks, he told his wife, “I think I understand this stuff. I know what the problem is. But fortunately, I’m too smart to take it up professionally. I’d be ridiculed. Nobody would believe me. They would say, ‘You’re not a scientist, you’re a law professor.’ It would be something, once you got started with it, you’d be involved in a lifelong, never-ending battle.”

“That,” says Phillip Johnson, remembering back with a smile, “was of course irresistible. I started to work the next day.”

Everything in him is absorbed by one exclusive interest, one thought, one passion—the REVOLUTION.—Mikhail Bakunin

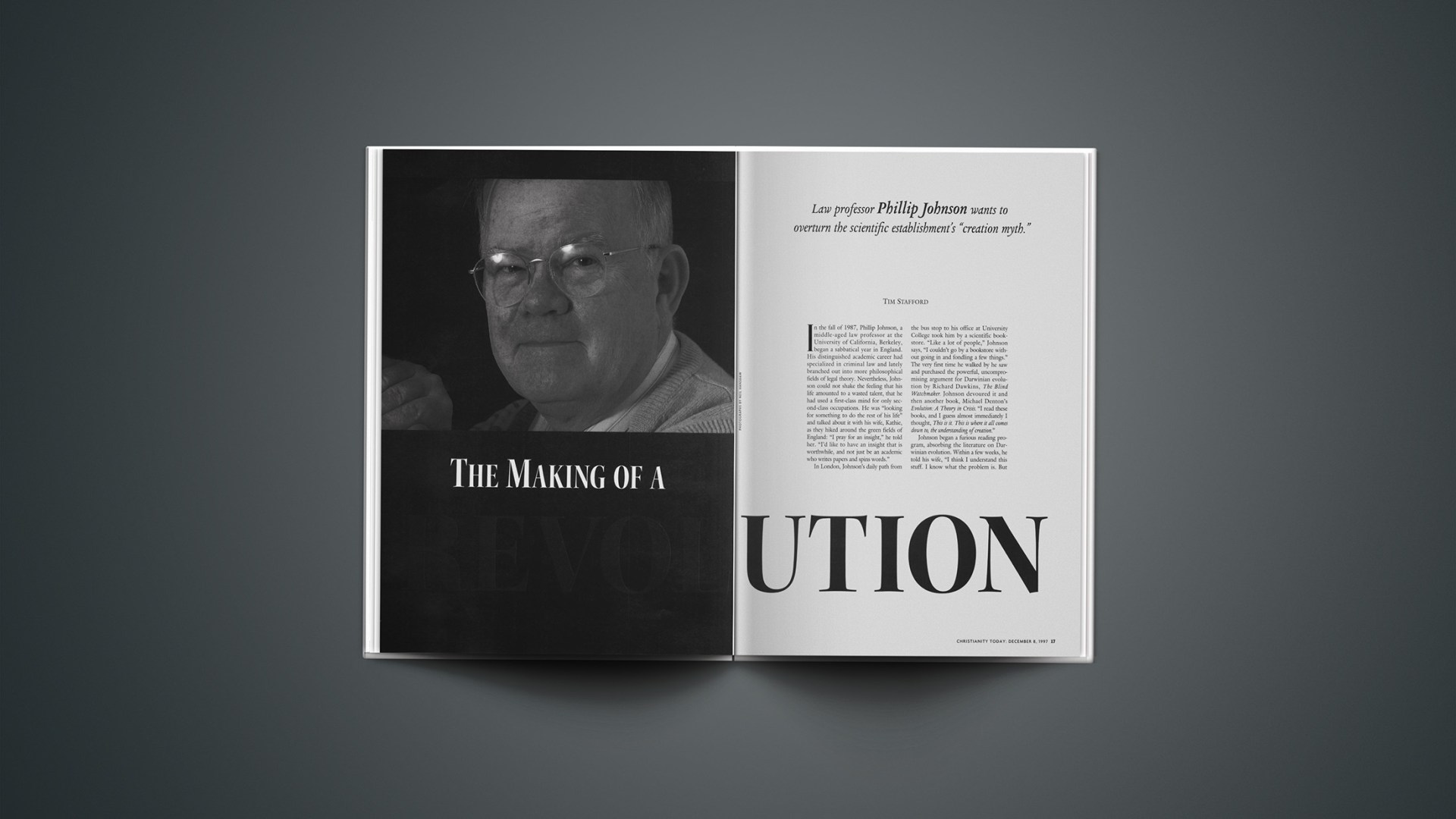

Johnson does not look like a revolutionary. He does not even look like a Berkeley law professor, who (one might expect) should bristle in one way or another. Johnson carries a large, round, spectacled head on an ordinary body, looking vaguely pleasant and innocuous. His Berkeley home is small and exquisitely ordinary, unusual only in that his wife houses her 22,000 children’s books in the basement, opening it regularly as a private library for neighborhood kids. Johnson is friendly, unpretentious, and barely capable of small talk. He loves intellectual conversation and can talk it nonstop, forgetting all else, such as where he is driving.

Once Johnson had sunk his teeth into evolutionary theory, it dominated his thoughts, his work, his conversation. While law—and criminal law, particularly—might appear to be the very worst academic preparation for attacking evolutionary theory, in fact it served Johnson well. Criminal lawyers consider how to present evidence and argument convincingly. (As the O. J. Simpson trial demonstrated, evidence alone won’t convince a jury.)

Reading evolutionary theorists, Johnson thought of clever lawyers presenting a flawed case. Steve Meyer, a young philosopher of science then studying at Cambridge University, remembers Johnson saying that “something about [the evolutionists’] rhetorical style made him think they had something to hide.”

“I could see,” Johnson says, “that Dawkins achieved his word magic with the very tools that are familiar to us lawyers. [He was] deciding everything in the definitions. ‘We define science as the pursuit of materialist alternatives. Now, what kind of answers do we come up with? By gosh, we come up with materialist answers!’ If you take as a starting point that there’s no creator, then something more or less like Darwinism has to be true as a matter of definition. It’s only a question of the details.

“Dawkins really gives it away when he speaks of universal Darwinism, which is his concept that if life evolved on distant planets on the other side of the universe, it must have evolved by Darwinian means. Why? Because that’s the only thing that can happen once you rule a creator out of existence. You don’t need evidence.”

Soon Johnson had a book-length manuscript, which would become (three years later, after many drafts) the controversial Darwin on Trial. (A more popular version has recently been released from InterVarsity Press, Defeating Darwinism by Opening Minds. ) Meyer carried the manuscript to a Tacoma, Washington, meeting of scholars interested in “intelligent design”—the renegade theory that the natural world is best explained as a design rather than a chance development. From this group would come allies and friends. (A constant chatter of e-mail goes on through the Web site for Access Research Network—http://www.arn.org/arn.) Johnson tracked down all who showed interest, engaging them, encouraging them, learning from them.

He was just as interested in meeting opponents. A fellow law professor, also on sabbatical in England, sent Johnson’s manuscript to Cornell evolutionary biologist William Provine. “I thought it was worse than most of the garden variety creationist tracts,” Provine says, and he wrote back a critique. “Phil wrote, ‘You think what I believe is ridiculous; look at what you believe,’ and we got into a wonderful correspondence.” Eventually the two met in debate—the first of many Johnson would have with Provine and other scientists.

“Phil Johnson’s genius is to do these debates and come away as friends,” says Paul Nelson, a graduate student in philosophy at the University of Chicago. Johnson genuinely enjoys the cut and thrust of argument and doesn’t seem to take it personally when he is attacked. After a sizzling public debate with an antagonist like Provine, Johnson is likely to go out for a beer and more talk. (Provine, who is fighting a brain tumor, speaks with deep appreciation of Johnson’s friendship.)

For Johnson, it is important not merely to crack open the discussion. It also matters what kind of discussion follows. “I love disagreements. But we must turn them into things that can be argued about, that can be compromised if you can’t persuade. That is the ideal of the rational civil society.

“You never win unless you win by the right methods. I don’t mean that in some kind of woollyheaded idealistic way. I’m talking hardheaded strategy here. Fights are often very healthy. What has gotten us into such a mess is victories that were won by the wrong methods: civil wars, religious wars, oppression.

“There is a question of how actually to do cultural battles with enough aggressiveness to make a difference and to make a point, and yet in a way that they end up healing. I’m always trying to learn better how to do that myself. That’s why it’s important to me that Will Provine says that we’re going to have a beer afterwards. That’s the picture I want to leave—that the ferociousness of the argument doesn’t mean that there is vindictiveness.”

Johnson does not show a need to dominate or impress or “win.” He says he plays for a draw in debate. “What I want is for people in the audience to leave saying, ‘There’s more to this than I’d realized. I’d like to hear about this again. This is interesting.’ “

Injustice, poverty, slavery, ignorance— these may be cured by reform or REVOLUTION. But men do not live only by fighting evils. They live by positive goals, individual and collective.—Isaiah Berlin

Johnson grew up as a brainy wunderkind in the town of Aurora, Illinois. By his own memory, he was arrogant and obnoxious, too smart for his own good. He could hardly wait to get out of town. Reading the Harvard University catalogue, he discovered that on rare occasions the school considered applications from high school juniors. He applied and was accepted.

Harvard, however, failed to capture his attention; he says he was a lukewarm, disengaged student. Having no idea what to do after graduation, Johnson taught school in rural Kenya, then went home to learn that his father had helpfully put in his application for the University of Chicago law school. With no better alternatives at hand, Johnson went off to classes and discovered, for the first time, something hard enough to interest him. He graduated at the top of his class, clerked for the chief justice of the California Supreme Court, and then got the ultra-plum position of clerk for Earl Warren, chief justice of the United States Supreme Court. Afterwards Johnson was offered a teaching position at Berkeley and took it.

Johnson genuinely enjoys the cut and thrust of argument and doesn’t seem to take it personally when he is attacked.

Berkeley was an ideal platform for a brilliant legal scholar. But its charged atmosphere also worked to shake Johnson free from everything he half-believed. A moderate liberal, he actively opposed the Vietnam War but was repelled by the group-think he saw on the Left. Yet, while serving as the law school’s associate dean for academic affairs during a turbulent period in the early seventies, he found, perversely, that he envied the very radicals who repelled him. “Misguided as they were, they believed in something, and I was just doing my institutional duty. That whole experience led me to begin to ask, what is so great about this agnostic rationalism I have been taught?”

His personal life was not going well, either. When his wife told him one day that she was leaving, he didn’t fight it; their marriage had been on the rocks for some time. They agreed to tell the children the next evening. First, though, he had a duty to perform. His 11-year-old daughter was attending Vacation Bible School at the invitation of a neighboring friend. She wanted a parent to attend the final dinner, and Johnson had said he would go. Understandably, he had a lot on his mind as he listened to the pastor make a brief presentation.

“To this day I can’t remember any of the content of it. What I remember thinking at the time was, You know, he really believes this—and I could too. I could be like that. It became part of my plausibility structure. Why not? What’s so good about what I’ve got?”

Though a lifelong agnostic, Johnson had read and admired C. S. Lewis, Dorothy Sayers, and J. R. R. Tolkien. “When I was in junior high school I went through a Clarence Darrow/Bertrand Russell phase, but by the time I was in college I’d outgrown that. I was more of a Dostoyevsky lover. I thought Christianity was a wonderful thing. I just thought, It’s too bad it’s gone. It’s not for people like me. I was socialized into a culture that took that for granted, and never reconsidered it.”

At some friends’ invitation, he began attending First Presbyterian Church of Berkeley and eventually made a Christian commitment. He met his second wife, another adult convert, through the church. Most important, for the purposes of this story, he began to see the world through a different set of lenses, to reconsider a whole set of assumptions he had held.

“Every REVOLUTION was first a thought in one man’s mind.”—Ralph Waldo Emerson

When Johnson was a student at Harvard he had gone to see Inherit the Wind, the film version of the Scopes trial. The smart Harvard-Yard audience, Johnson remembers, laughed heartily as the film version of Clarence Darrow made a monkey of William Jennings Bryan and his foolish arguments against evolution. Johnson did not join the laughter. Listening, he felt a wave of revulsion. The target was too easy, he thought, and so was the audience’s self-congratulatory smugness.

The irony was that university students thought of themselves as daring rebels for holding orthodox materialist views; they actually considered themselves liberal for scorning ignorant fundamentalists. Instinctively, Johnson disliked the attitude. Now, many years later, he began to think his reaction through.

Invited by the Stanford Law Review to write a review of “Critical Legal Studies,” a movement of radical legal scholars, Johnson found himself surprisingly appreciative. While unattracted to their left-wing politics, he found that they criticized liberal rationalism much the way he was beginning to—for deciding all questions by manipulating the terms, so that moral judgments were clothed in a sham neutrality. “The struggle to establish which values will predominate,” he wrote, “is to liberal rationalism what sex was to the Victorians: We know that it has to go on, but decent people don’t talk about it in public.” He argued that “clear thinking is furthered when we overcome our fear of addressing religious issues and of labeling them as such,” in part, because “labeling all quests for ideal solutions or for transcendent values as ‘religious’ counteracts the single most mystifying concept of our time—the notion that there is a ‘scientific’ solution to the problem of morality, an ideology or philosophy that can generate values out of purely natural materials and logic.”

A conference of Christian university professors stimulated other thoughts. The professors were asked how faith affected their scholarship. Most said that Christianity affected their attitude toward their students but made no direct impact on their ideas. “I remember that when a professor of engineering said it didn’t have any effect, I found that unremarkable, but when the professor of English literature said that, I was stunned.

“What we were all doing was taking a naturalistic approach for intellectual purposes. It seemed to me that the pervasive naturalist approach made sense only if naturalism was true. To put it another way, saying ‘God doesn’t exist’ is a position I can recognize as coherent. Saying ‘yes, God exists, but the wise way is to proceed as if he didn’t,’ that seems to me to be preposterous.

“Why do people get this idea that naturalism is the only way to proceed? They think that it’s been validated by science. At the very heart of that scientific validation is the story of life, the story of our creation.” Darwinian evolution, as Johnson eventually came to see it, undergirds a whole mode of thinking that has no need of God. “If it were only science that was at stake, nobody would care about it so much, including the scientists.”

Evolutionary theory, Johnson contends in his second book, Reason in the Balance, is the naturalists’ creation myth. It establishes scientists as high priests of truth and asserts rather than proves a thoroughly materialistic world-view—that everyone and everything is a mere product of matter and chance. “They think they are going to get rid of religion, that’s where all the dogma and irrationality come from, and then we’re going to have the life of reason. That’s the Bertrand Russell school of nineteenth-century rationalism.” (Thus Johnson calls Provine “one of the great minds of the nineteenth century.”)

In reality, Johnson says, naturalism undermines reason. “Richard Rorty says, ‘Darwinism means there is no objective rationality. All we know is what’s good for us.’ The obvious conclusion from that is, believe whatever you want to believe.”

Darwinian evolution says that the brain evolved strictly as a means to one species’ survival. Why should it be capable of knowing truth? By evolutionary standards, a more postmodern version of truth would be likely—truth as a means of hegemony, a way for one group to outsurvive another. “Deconstruction,” Johnson says, “is the natural child of scientific rationalism and the materialist world-view.”

A non-violent REVOLUTION is not a program of seizure of power. It is a program of transformation of relationships.—Mohandas Ghandi

Phillip Johnson’s idea of revolution is not, then, a struggle to control one corner of the ivory tower. He is playing for all the marbles—for the governing paradigm of the entire thinking world. He believes evolution’s barren rule can be overturned, that it is ripe for revolution. He hopes to rejuvenate rationality, to turn disagreements into “things that can be argued about.”

Johnson mainly uses an Emperor’s New Clothes argument against evolution. He says it has been 140 years since Darwin introduced his theory to the world, and what do we have to show for it? For all the brave talk about evolution as an established fact, much of the evidence actually seems to run against Darwinism, as, for example, fossils that don’t show creatures gradually changing but rather staying the same. Yet Darwinists so want the theory to be true they obscure the evidence.

Thus, Darwinian apologists persistently conflate microevolution with macroevolution, Johnson says. They repeat the same few stories about finches changing their beak size, moths changing from white to gray and back again, and dogs transformed from Pekinese to poodles, never seeming to notice that change within an existing gene pool is a far cry from what Darwinism actually claims, the creation of a whole new gene pool for an entirely different structure. Just when and where will Darwinists demonstrate that one species typically becomes something completely different? Is there any evidence, Johnson asks, that what they say must have happened did in fact happen?

A good theory, Johnson points out, should be enriched and reinforced by new discoveries as time goes on. Instead, Darwinism seems to inherit new problems whenever anything new turns up. Johnson points to the recent discovery that catastrophes cause most extinctions, a finding that upsets the Darwinian scenario of new variations on a species thriving while others gradually die off. Citing biochemist Michael Behe’s Darwin’s Black Box, Johnson says Darwinian theory has not even tried to explain itself at the level of molecular cell biology, although cell biochemistry has been at the forefront of scientific discovery in this generation. As Johnson sees it, Darwinism is a relic of another time, propped up by the ferocious orthodoxy of its followers, whose main answer to any intellectual challenge is to bring out the bogeyman: “creationism.”

Johnson burst on the scene as a certified intellectual heavyweight, energetic and fearless, hard to ignore. Darwin on Trial was scornfully reviewed by major scientific publications, but it was reviewed. In the Scientific American, paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould called it “a very bad book,” “full of errors, badly argued, based on false criteria, and abysmally written.” He even lectured Johnson at length on his writing style, which gave away Gould’s bias as clearly as anything, for Johnson is (like Gould) a fine essayist.

Johnson was not terribly worried about such treatment. He expected it and had enough faith in the academy to believe that he would eventually be heard if he could sustain the argument. That, however, was a substantial “if.” It was not enough to be right; he must find allies.

When Johnson published Darwin on Trial, his potential allies were on the fringe of university scholarship and badly divided among themselves. Creationism was dominated by Henry Morris’s Institute for Creation Research (ICR), a group that holds to a biblically literal “young earth” created a few thousand years ago. They have not convinced many scientists to take them seriously, and their views have become a convenient target for those determined to keep “creationism” out of the public schools. Though scorned by biologists and geologists, ICR has kept up a noisy barrage against evolutionary theory, winning the allegiance of many conservative Christians. In some church circles, the ICR’s positions had become the only options.

For many Christians working in science, and particularly for the science faculty at many Christian colleges, ICR is an embarrassment. Christian scientists find themselves caught between their secular colleagues who scorn the idea of bringing God into science, and their conservative students and churches, deeply suspicious of anyone who does not hold to a six-day creation.

Some Christians in science, labeled “old-earth creationists,” accept findings that the Earth is billions of years old, yet think that the universe shows itself as a product of “intelligent design” rather than blind materialistic processes. Others take a more philosophical perspective. Sometimes called “accommodationists,” because they “accommodate” evolutionary theory in their world-view, they believe that evolution should be accepted and understood as an aspect of God’s creative power. They speak of God as creator but accept a version of science that looks only at material causes. For them, science and theology can only conflict when one or the other exceeds its boundaries.

“I think the rest of society is perfectly justified in saying to the evolutionary biologist, go away and stop bothering us.”

Johnson has managed both to energize and irritate such people—to find both allies and enemies. Part of the irritation is that he has worked out a cautious truce with the ICR. “I’ve been invited again and again to denounce Creation Science. Darwinists would say, ‘You have to renounce all creationists who previously existed, or we won’t talk to you.’ (Of course, once they had gotten you to do that, they wouldn’t talk to you either.) I’ve always refused to do that. I do not believe that biblical creationism can be described as a failure or as immoral. They have held the lines against a complete takeover by scientific materialist ideology. This required great courage. They have taken such a horrible bashing. I respect that.”

Johnson wants to leave open questions about how God created. “I want to develop a challenge to materialistic evolution. Let’s unite around the Creator. After that we can have a marvelous argument about the age of the earth.”

But as David Wilcox of Eastern College explains, “Phil has not been in a church where you don’t want to tell them what you studied, because if they discover that you don’t hold a young-earth interpretation of Genesis, you’re defined as a wolf in sheep’s clothing.” In other words, Johnson doesn’t understand how troublesome the ICR can be.

Johnson has impatiently criticized believers who accommodate evolution. To him, they hold an incoherent position, and he says so. But, Wilcox says, the positions Johnson criticizes have been arrived at painstakingly. “You may not be at the right spot, but you’ve put some effort into trying to put theology and science together. If you’re accused of lacking integrity, that’s painful.”

Calvin College physicist Howard Van Til, one of Johnson’s outspoken opponents, says Johnson “makes a number of very harsh accusations about teachers at Christian colleges, that they have swallowed the presuppositions of naturalism, that they are thirsty for approval of nonscientific peers, that they are willing to do and say anything to maintain funding for research.” While applauding Johnson’s criticism of atheistic scientism, Van Til thinks Johnson’s interest in “intelligent design” will lead to a scientific dead end.

“No one makes a REVOLUTION by himself; and there are some revolutions, especially in the arts, which humanity, accomplishes without quite knowing how, because it is everybody who takes them in hand.”—George Sand

Nevertheless, Johnson has found allies. A young biochemist at Lehigh University, Michael Behe, read Darwin on Trial and looked forward to reading thoughtful responses in the scientific press. He was furious when, instead, he got antifundamentalist diatribes that he considered “anti-intellectual.” Science printed his irate letter. A week later Johnson wrote to him, a dialogue began, Johnson invited him to a conference where Darwinians and creationists discussed Darwin on Trial, and Behe was gradually pulled into Johnson’s network. Behe’s Darwin’s Black Box was a major new advance for Johnson’s team (see “Meeting Darwin’s Wager,” by Tom Woodward, CT, April 28, 1997, p. 14), especially as it came not from a lawyer or philosopher but a biochemist.

Behe’s experience is somewhat typical. Knowing that one man cannot make a revolution, Johnson writes potential allies, he calls them up out of the blue, he exchanges a blizzard of e-mail messages with them. A series of conferences (some backed by the Fieldstead and Company, a conservative foundation) have drawn in an expanding group of friendly academics. Last year’s “Mere Creation” conference at Biola University in Southern California was the largest yet, with over 160 invited academics present. Johnson remains the hub of the wheel, but there is proliferating excitement and collaboration. Other books, in other fields, are in the works. A giddy hope shows itself, that the revolution is really possible.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if Darwinism as we know it goes belly up,” enthuses mathematician William Dembski, who is bringing probability theory to bear on evolution and design. “The ideas are on our side. When I look at the evolutionists’ literature, the sense I get is that they keep going over the same old ground.”

Johnson speaks of a “wedge” strategy, with himself the leading edge. “I’m like an offensive lineman in pro football,” he says. “The idea is to open up a hole that a running back can go through. My idea is to clear a space by legitimating the issue, by exhausting the other side, by using up all their ridicule.” His evident enjoyment of controversy suits him for the role. “I’m like a kid in the candy store,” he says. “I can’t think of anything I would rather be doing.”

Part of Johnson’s strategy is to keep the Bible out of the discussion. He wants to deflect fear that he is a stalking horse for religious fundamentalism, a fear that can wreck almost any discussion. “I gave a lecture at the University of Oregon recently,” says Johnson, “and it’s just typical. I’m giving my lecture about distinguishing materialism from the empirical evidence and admitting that the Cambrian explosion is a heck of a big problem for Darwinism. A professor of paleontology puts up his hand, and says, ‘Which God do you want me to talk about, the God of the Hindus, the God of the Baptists, the God of the Catholics? There are all these different gods. How can I teach about one god in my paleontology class?’

“This is in a sense totally irrational. I don’t want him to talk about God in his paleontology class. I told him to give the fossil evidence honestly, instead of shading it to protect the materialist theory from being discredited.” (Still, Johnson later admits, “I sometimes get uncomfortable thinking about my own side. This notion that there is even today in the whole religious impulse a potential for fanaticism and irrationalism is not unfounded. My goodness, everybody who has ever been on a church committee knows that.”)

Scientists ask Johnson to offer his scheme of origins. After all, he critiques their theories. Does he have a better idea? Can he articulate how “intelligent design” would work? Johnson won’t play. He has no intention of letting the discussion shift away from criticism of Darwinian theory.

“It’s important to understand why it’s not a legitimate demand. I am not applying for a graduate program in biology. I am not planning to take part in a biological research project. What I know is that the scientific community is telling the citizens that for all purposes you should accept materialism as true. You were created by an unsupervised, purposeless, materialist process, and we’ve proved that. I’m telling them, well, actually, I don’t think you have proved it. I think you’ve been ignoring and suppressing massive evidence against that position, and you are misrepresenting this to the people. So what if we don’t have a complete answer to how creation worked? I think the rest of society is perfectly justified in saying to the evolutionary biologist, ‘Go away and stop bothering us. We’re not obligated to accept your dogma, and we’re not obligated to provide another one in its place, either.'”

Scientists have become our priests, Johnson says, telling us how we came to be and what we can put our faith in. “Our priests have certainly worked miracles. They put a man on the moon, they explode a nuclear bomb. You figure, these people must know something. And of course, they do know something. But they don’t know everything that they say they know.”

The revolution Phillip Johnson wants would turn those priests back into ordinary people and free all of us to consider the unthinkable—a God who can touch our world, and whose mind gave our minds their capacity for truth.

Copyright © 1997 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.