On a pleasant July evening in western New York, two distinct groups of people file into the open-air amphitheater just up the hill from Lake Chautauqua. The denizens of the Chautauqua Institution—founded in 1874 to train Sunday-school teachers—are overwhelmingly white, elderly, upper middle class, and terminally addicted to learning and the arts. During most nights of the summer season, after a full day of lectures and symposia, Chautauqua offers a performance of some kind at the pavilion—ballet, Chautauqua’s own symphony orchestra, or, as on this night, an outside musical group. Residents and visitors are accustomed to wandering in the direction of the pavilion after supper to locate friends and sample the cultural offerings.

The other constituency on this summer evening clearly had been looking forward to tonight’s performance, by a band called Jars of Clay, for some time. A group of high-school and college-age students congregated in the orchestra section and, in anticipation of the concert, executed a call-and-response cheer that has become commonplace at Christian music concerts: “We love Je-sus! How about you?” The other side answered: “We love Je-sus, too! How about you?” Some of the older folks, looking up from their books or news papers, seemed a trifle befuddled by this uncharacteristic outburst of religious enthusiasm.

A few minutes after eight the orchestra section began a rhythmic clapping. Machines blew artificial smoke across the stage. The orchestra section rose to its feet, and those in the out lying seats again looked up from their reading. The main event took the stage and opened with “Liquid,” the first song on its debut, self-titled album, Jars of Clay. The music was loud, but there was a sweetness here.

This is the one thing,

The one thing that I know.

Blood-stained brow,

He wasn’t broken for nothing.

Arms nailed down,

He didn’t die for nothing.

As the group moved on to “Tea and Sympathy,” a cut from its second album, Much Afraid, the orchestra section swayed back and forth in time to the music, arms upraised and interlocked.

The older folks in the upper reaches of the pavilion weren’t so sure, offering only polite applause. A bearded man in his early fifties wadded cotton in his ears to stave off the decibels. An elderly woman left after the second song. “We’ve heard that nine different presidents have been on this stage,” Dan Haseltine, the lead singer, said between songs. “I suppose if you put them all together they could probably rock.”

Banter is not Jars of Clay’s strong suit. The band members are young, barely older than college age themselves. They have affected something of a grunge look—several of them seem to take pains to convey the impression they have spent more time with a parole officer than a youth pastor—but it appears that they would be just as comfortable in polo shirts or even neckties. The band members met as students at Greenville College, a Free Methodist liberal-arts school in central Illinois, where they majored in something called “Contemporary Christian Music.”

In the fall of 1993, Haseltine, Charlie Lowell, Stephen Mason, and Matt Bronleewe collaborated on an original song, “Fade to Grey,” for a studio project in a recording class. They performed at a campus hangout, Underground Cafe, and the response emboldened them to work on other musical compositions. When it came time to choose a name, Lowell, the keyboardist, suggested Jars of Clay, from 2 Corinthians 4:7: “But we have this treasure in jars of clay to show that this all-surpassing power is from God and not from us” (NIV).

During the spring semester in 1994 the group produced more songs and made a couple of appearances at music festivals. Someone noticed an advertisement for a talent contest; Jars of Clay submitted a demo and became one of ten finalists. On April 27, 1994, they performed in Nashville for the Gospel Music Association Spotlight Competition and won grand prize as the best new Christian band. By the time they returned to Greenville to complete the semester they were receiving phone calls on the pay phone in their dormitory with offers of contracts from record companies.

That summer they decided to make a run at a music career, although Bronleewe elected to continue school and get married. Lowell recruited his friend from high school, Matt Odmark, to take Bronleewe’s place at guitar, and the group moved to Tennessee. During the fall and winter they produced their debut album, which was released in May 1995 to critical acclaim. “Quite possibly the hottest new band of 1995,” one reviewer exuded, “pure acoustic music with a rock twist.” Another review cited their “creative excellence” and said that the opening track “blows the doors off the walls that still separate Christian rock from the greater world of music.”

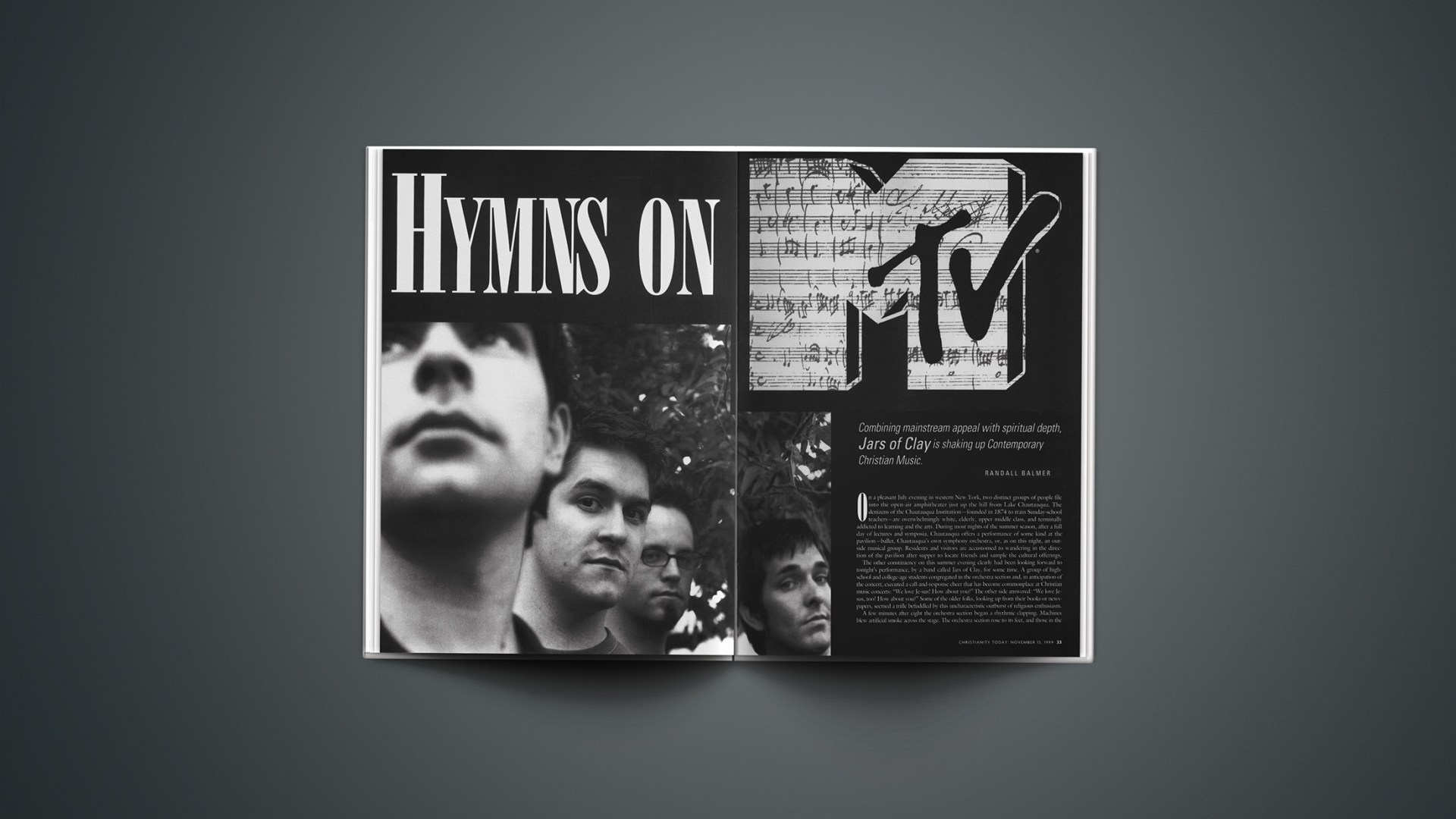

Fans apparently agreed, sending the album to double-platinum status and a Grammy nomination for Rock/Gospel Album of the Year. “Flood,” a song about the deluge of Noah’s day, crossed over onto alternative and “mix” stations as well as MTV and VH1. Overall, according to April Hefner in CCM magazine, Jars of Clay had enjoyed “the most successful Christian music debut ever.”

Much Afraid, the second album, did even better, winning the Grammy in 1997 for Pop/Contemporary Gospel Album of the Year and several other awards. According to Jennifer Bachman, an agent for an other Christian artist, “Jars of Clay has become a standard of comparison in contemporary Christian music.”

The band’s third album, If I Left the Zoo, also is adventurous (see “Jar Boys Meet Sgt. Pepper,” p. 38).

Warren Pettit, an associate professor of music at Greenville College, has had ample opportunity to reflect on the success of Jars of Clay. As the faculty member most involved with those majoring in “Contemporary Christian Music,” Pettit has been asked countless times if he anticipated that the “Jar boys,” as they came to be called, would make it big. When I put the question to him he shook his head and shrugged. “Of course not,” he said. “They were just students freshman year like everybody else.” Pettit began to take notice, however, when he accompanied the group to a performance at one of the side stages at a Six Flags theme park. “I saw that a bunch of junior-high girls were walking by. They stopped, sat down, and listened.”

Pettit clearly remembers the day a student engineer burst into his office with a mix of “Fade to Grey.” “What do you think?” the student asked excitedly, after Pettit listened to the cut. “I don’t know,” he replied, “because I’ve never heard anything like this.” The musicologist in him eventually waxed analytical. “If I had to deconstruct what they were doing, they were using what we call samples or loops—two- or four-bar drum or percussion sound bites repeated over and over—then on top of that was a folk-acoustic-guitar-rock sensibility. But the way they had organized it,” Pettit said admiringly, “there was just something different about it.”

In order to understand the appeal, however, you have to mix in what Pettit calls the intangibles: the artists themselves, the music, the lyrics. “If you take the totality of all that,” he said, “there was something quirky about it. I thought they were very brave and clever in assimilating what appeared to be very dissimilar elements.” Pettit was particularly taken with the combination of a Gregorian chant with a rhythmic dance sample in “Liquid,” but he also cited the whistling, the use of a child’s voice, as well as a recorder and stringed instruments. “Jars of Clay rejected the mechanistic, techno, synthesizer pop of the late 1980s,” Pettit said. “It wasn’t part of their vocabulary.”

The music industry was enchanted, and the “Jar boys” climbed aboard what Pettit called “an absolute ballistic missile” to stardom. For Jars of Clay the fast track to success was heady at times—concert appearances with Sting, The Late Show with David Letterman, several motion-picture soundtracks, and a jealously protective management that insisted, for example, the band members were so busy that I couldn’t conduct even a brief interview until the following year.

An altogether too brief, unscientific, and occasionally irreverent history of evangelical music in America might sound something like this: We begin with the Bay Psalm Book, published by the Puritans in 1640. The Puritans, of course, shunned ostentation the way John Calvin avoided the Song of Solomon, and so they sang Psalms to simple meters. Isaac Watts introduced his Psalter, a paraphrase of the Psalms, to England in 1719; the American edition, printed by Benjamin Franklin, appeared a decade later. Evangelical music during the revival and camp-meeting era of the Second Great Awakening conveyed the simple doctrines of evangelical piety, and the rise of Methodism introduced the stirring, sometimes magisterial music of John Wesley and Charles Wesley into the evangelical hymnal.

The feminine ideal of piety in the nineteenth century, especially when combined with the temperance crusade, brought overtones of sexuality and sentimentality to evangelical music. Faithful, patient mothers waited for their wayward sons to return home and come to Jesus—”Tell Mother I’ll Be There”—and the intimacy was apparent in such songs as “Jesus, Lover of My Soul,” “My Jesus, I Love Thee,” and in the enduring popularity of “Rock of Ages, Cleft for Me.” A resurgence of muscular Christianity at the turn of the twentieth century sounded the notes of militarism: “Lead On, O King Eternal,” “Stand Up, Stand Up for Jesus,” “On ward, Christian Soldiers.” It is not surprising that, during the carnage of the world wars, hymns about blood were popular in evangelical churches—”Nothing but the Blood of Jesus,” “Are You Washed in the Blood?” Evan gelicalism sustained the notes of triumphalism—”Victory in Jesus,” ” ‘V’ Is for Victory”—through the Cold War.

The most dramatic changes in evangelical music since the colonial period began in the tumultuous decade of the 1960s. Throughout American history evangelicalism has demonstrated a remarkable knack for survival by tapping into the prevailing popular tastes. Although it would be an understatement to say that evangelicals were slow to warm to rock ‘n’ roll, by the late sixties some evangelical musicians recognized that the strains of “Make Me a Blessing” and “Bringing in the Sheaves” (which I used to think was my mother’s laundry song: “bringing in the sheets”) could no longer compete with “Hey Jude,” “Alice’s Restaurant,” and “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction.”

At least partially at the behest of the Southern Baptist Convention, Ralph Carmichael—an evangelical musician who had grown up enamored of the big bands—decided to try his hand at composing sacred music that would be more palatable to the younger generation. He sprouted mutton-chop whiskers, and although his pieces still favored the big, symphonic sound of violin strings rather than electric guitar strings, his compositions—including “A Quiet Place,” “Pass It On,” and “He’s Everything to Me”—quickly became popular with the under-30 crowd. Soon many evangelical congregations faced the prospect of either supplementing or replacing the venerable old hymnals that had been around for what seemed like, well, generations.

The Jesus movement, just then aborning at Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco and on Huntington Beach in Orange County, carried Carmichael’s revolution even further. Chuck Smith and Calvary Chapel, located in Costa Mesa, California, lured hundreds of hippies into the evangelical fold, and many of them, unfettered by the conventions of middle-class evangelicalism, unleashed a remarkable burst of musical creativity. The melodies of groups like Love Song, Danny Lee and the Children of Truth, and others that appeared on the Maranatha! label in the early 1970s were simple and unpretentious, utterly without guile and largely innocent of theological categories (with the possible exception of premillennialism). Larry Norman—whose rhetorical mantra was “Why should the devil have all the good music?”—added the harsher sounds of rock ‘n’ roll, and a flurry of other artists followed his lead, including John Fischer, Andrae Crouch, Chuck Girard, Keith Green, and Randy Stonehill.

As Norman and his confreres entered the music scene, however, other, larger forces were at work in American evangelicalism. For the first time in nearly half a century (since the Scopes trial of 1925) evangelicals were beginning to venture, albeit tentatively, out of their cozy subculture into the larger world. Even this modest dangling of toes into the water was heady and invigorating; for someone who grew up singing in the junior choir, the possibility that long hair and rock ‘n’ roll might be justified for spreading the gospel was positively titillating. Besides, if Jerry Falwell—who in 1965 had declared that he “would find it impossible to stop preaching the pure saving gospel of Jesus Christ and begin doing anything else”—could form Moral Majority as a political lobby in 1979, then clearly the rules of evangelical engagement with the larger culture were changing. Evangelicalism was still a subculture, but it was no longer a counterculture, as it had been during the middle decades of the twentieth century.

The 1980s will be mistaken by no one for a golden age of creativity. As his critics were fond of remarking, Ronald Reagan brought to Washington some of the greatest minds of the seventeenth century—and evangelical music fared little better. With few exceptions, it was derivative and predictable, reflecting a kind of “me too” approach to secular music. Countless evangelical groups aspired to mimic the folk music of Peter, Paul, and Mary or the popular ballads of Simon and Garfunkel. Amy Grant and Sandi Patty were the Belinda Carlisle and Barbra Streisand of evangelical music, and as long as heavy metal remained part of the secular music vernacular, several evangelical bands—like Petra, Stryper, Guardian, and Whiteheart—sought to baptize heavy metal.

The justification for all this was that these evangelical musicians were simply preaching the gospel in a new medium and that all you had to do was pay close attention to the lyrics. True enough, perhaps, but the lyrics tended to be facile, sometimes a mere reworking of pronouns so that the pining “I love you” songs of secular music became “He loves you.” In the case of heavy metal (or, more recently, reggae and ska) critics insisted that the “gospel message” was so buried beneath the beat and the pyrotechnics and the keening guitars that it would take J. Edgar Hoover and his minions several weeks to unearth it.

The musicians themselves tended to ignore their critics, especially the older generation of naysayers. Contemporary Christian Music, as it came to be called, was nothing if not popular, with a market share that grew every year. Several artists, notably Amy Grant and Michael W. Smith, became “crossover” stars when their releases were ranked on both the Christian and the pop charts. Contemporary Christian Music was a huge industry, not merely a niche market, bringing in an estimated three-quarters of a billion dollars annually by the mid-1990s. In the late 1980s and early 1990s several labels were taken over by secular corporations that recognized the potential for profits.

In 1998, according to Billboard magazine, the Contemporary Christian Music market share of the recording industry had exceeded that of jazz, classical, New Age, and soundtracks.

“Pride is one of those things that tells us we can do anything on our own,” Haseltine tells the Chautauqua audience. “This is a song that talks about breaking down pride and experiencing love.”

The marionette has your number

Pulling your arms and legs till you can’t stand on your own

Dragging your conscience on the stage

and your heart gets rearranged

and you cannot tell your mentor from your Maker

Here, it seems, lies the classic evangelical dilemma of being in the world but not of the world, along with warnings about fleeting fame.

Look at the crowds bleeding with laughter

Over the way you entertain at beck and call

They don’t see behind the lights, or the painted background

They just like to see you fall

Another song, “Worlds Apart,” rehearses the importance of humility and warns of the blandishments of what evangelicals used to call “worldliness”:

I am the only one to blame for this

Somehow it all ends up the same

Soaring on the wings of selfish pride

I flew too high and like

Icarus, I collide

With a world I try so hard to leave behind

To rid myself of all but love

to give and die.

A theological gloss here might point out that it is pre-eminently our attachment to this world that mires us in self-absorption. Jesus calls us to self-renunciation.

To turn away and not become

Another nail to pierce the skin of one who loves

more deeply than the oceans,

more abundant than the tears

Of a world embracing every heartache.

The refrain includes the phrases “take my world apart” and “broken on my knees.”

Lyrics like this may come at a propitious time for evangelicals. In the middle decades of the twentieth century, worldly was the most damning epithet you could level at another evangelical. The stigma of “the world” began to dissipate, however, as evangelicals themselves became more worldly in the 1980s, intoxicated by political power and apparent cultural influence. If these lyrics betray an awareness of the perils of fame and the enticements of the world, other Jars of Clay songs also suggest a theological maturity of someone way beyond his years.

Haseltine, still in his twenties, is the principal lyricist for the group’s compositions, although he routinely shares credit with other band members. The theology represented here is light years away from the cheap affirmation and the abject subjectivism of so much popular evangelical music since the 1960s, when the fare ran from “Jesus is just all right with me” to “Jesus made me higher than I’ve ever been before.” This “pronoun trouble” has persisted into the nineties and crops up everywhere—”You got me believing that You would die for me,” “You will never let me down,” “Love me good.” Sadly, much of this self-referential theology has leeched into the let’s-just-praise-the-Lord “praise music” now so ubiquitous in evangelical worship. Phrases like “Sing Alleluia to the Lord,” “Father, I Adore You,” “Jesus, You Are Wonderful,” and “Shine, Jesus, Shine” may evoke a reverential mood, but they carry little theological freight.

Just as Christian music has changed over the centuries, so too the theological sophistication evident in Haseltine’s lyrics heralds a shift in popular evangelical music away from the rhapsodic, dreamy mantras of praise songs and the self-absorption of contemporary recording artists. As Douglas Frank has observed, even though “a naked human being hangs at the center of the Christian faith,” evangelicals have devised all manner of theological conceits to divert attention from the dying Christ, and they do so, more often than not, by fixating on God the Father, all-powerful and triumphant. Haseltine’s theology pushes deeper, forcing us to look beyond the saccharine Jesus of evangelical sentimentality—”Jesus Is the Sweetest Name I Know,” “Precious Name, O How Sweet”—and gaze upon the naked, tortured body hanging on the Cross.

“The message of Christianity is a hard thing to want to spend time pondering,” Haseltine said in a CCM magazine interview with Hefner. “The fact that we are sinners, that apart from Christ we’re nothing, those are things that are not easy to listen to, and yet Christian music tries to make whatever they do easy to hear. It’s the good package mentality. When reality starts filtering into that, it tends to shake things up a bit because what people expect Christianity to be is not reality.”

The music of Jars of Clay invites us to consider again the Jesus on the cross. It dispenses with the triumphalism—the bravado and the posturing—that has infected evangelicalism for more than a century now: “We Shall Shine as Stars in the Morning,” “We Are More than Conquer ors.” The Jesus portrayed here is not the conquering hero, nor is he the heartthrob of some fawning adolescents. He is the Man of Sorrows, acquainted with grief. Jesus carries to the Cross the burdens of humanity, but therein lies the gospel, and the supreme paradox of faith is that only when we take full account of our sinfulness can we begin to understand the magnitude of grace:

Empty again

Sunken down so far … So I lay at Your feet

All my brokenness.

“It’s in despair that I find faith,” Haseltine writes; time and time again his words portray Jesus as the Suffering Servant.

Arms nailed down,

are you telling me something?

Eyes turned out,

are you looking for someone?

Eyes are another recurrent image in Haseltine’s lyrics. He writes in “Fade to Grey”:

Oh, it’s not hard to know what you’re thinking

When you look down on me now

“We’ve all grown up in the church,” Haseltine explains, with no hint of apology, and herein may lie a clue to the band’s effectiveness. Haseltine, like other contemporary artists, is grounded in evangelical theology, but he is not afraid to frame the rudiments of Christianity for a larger audience and to do so without resorting to evangelical jargon. “They approached music from the heart as opposed to formulas,” said Robert Beeson, the man who signed Jars of Clay to the Essential label, recalling what impressed him initially about the group. “They cut through the clutter in that there was nothing else like them.”

Haseltine himself puts it slightly differently. “We’re a band that likes to ask questions and get people to ask questions, and perhaps that will lead them to Jesus.”

For the Christian music industry in late April, all roads lead to Nashville for the annual convention of the Gospel Music Association, a gathering for recording companies, distributors, hordes of hyperactive publicists and press agents, and the artists themselves. My many months of persistence and dozens of phone calls had finally paid off. After I had furnished Jars of Clay’s managers with my life history, a theological statement, hat size, photo id, and a complete set of fingerprints, they graciously consented to allow me to fly to Nashville for what they assured me was at least a fifty-fifty shot at a half-hour interview during Gospel Music Week.

I approached the meeting with some trepidation, because in the intervening months I had become quite enamored of Jars of Clay, especially its lyrics, which seemed to represent almost a quantum leap beyond the pablum of most Christian music. What if the band members turned out to be vacuous, the intellectual equivalent of Cheez Whiz or Christian music’s answer to Britney Spears and the Backstreet Boys? As the fresh-faced band members shambled aboard the Essential Records tour bus for our interview, they looked a trifle bewildered, still more dazed than jaded from their sudden success. The band members hail from different theological backgrounds, ranging from Presbyterian and Episcopalian to the General Association of Regular Baptists, a denomination usually associated with a fairly starchy brand of fundamentalism. Although they attended Greenville, a school in the Wesleyan tradition, their theology is decidedly Augustinian or Calvinist, consistently portraying Christ as the relentless pursuer:

Someday she’ll trust Him and learn how to see Him

Someday He’ll call her and she will

come running and fall in His arms and

the tears will fall down and she’ll pray,

“I want to fall in love with You.”

These are sentiments with which Calvin and Martin Luther could agree. Both of them, echoing Augustine and the apostle Paul, insisted that sinners could do nothing to earn forgiveness; salvation was the gift of God, available by grace, through faith. “I believe that I have nothing to do with my salvation,” Matt Odmark declared without hesitation when I asked about the theology that informs the group.

Jars of Clay characterizes its musical style as “acoustically driven alternative pop.” When asked to list musical influences, members cite the Beatles, Toad the Wet Sprocket, Radiohead, the Jay hawks, Simon and Garfunkel, and James Taylor. I noted that they had listed no Christian artists. After an embarrassed silence Haseltine admitted, “I don’t think we have many influences in Christian music.”

That may account for the appeal of Jars of Clay to an audience that transcends the evangelical subculture. By tapping into mainstream music, they have avoided the lyrical and stylistic inbreeding that afflicts some of the other contemporary Christian music groups.

How effectively has Jars of Clay pushed beyond the boundaries of the evangelical subculture? The performance at Chautauqua provides one example, and in 1996 Jars of Clay turned down invitations to play at both the Republican and the Democratic National Conventions. (“We don’t want to be a political band,” Haseltine explained.) A friend informed me of yet another venue that had opened to Jars of Clay. Its music, he said, was popular in gay clubs in New York City. Imagine, he said, “three thousand gay men dancing to ‘Flood,’ and all of them with their shirts off.”

I asked the band members to imagine that. “Good,” Haseltine said finally, after the initial surprise had worn off, a surprise that seemed to be tinged with embarrassment. “That’s the way it should be.” Mason agreed. “I think we get excited at the thought of our music being played there,” he said. “We couldn’t reach them directly, but maybe our music can.”

Odmark saw the prospects for conversion. “If people dig the song and go out and buy the album and come to Jesus … ” His voice trailed off to consider the possibilities.

The popularity of Jars of Clay in markets beyond evangelicalism raises an issue that has bedeviled many Christian musicians. While crossover success remains an elusive goal for most Christian artists, those who have successfully crossed over into the secular music charts have faced stiff scrutiny from other evangelicals. Amy Grant probably set off the criticism with her hit single “Baby Baby,” and the latest chapter of the controversy was unfolding during Gospel Music Week.

A group called Sixpence None the Richer had released a single, “Kiss Me,” that had rocketed to the top of the secular charts. “Kiss Me” has roughly as much spiritual content as a steel-belted radial tire, but because the group had enjoyed initial success in the Christian market it begged the question of whether the song was “Christian” music. The Gospel Music Association has stepped in to adjudicate such matters, coming up with an unwieldy set of definitions that would be the envy of any Washington bureaucrat, but the fact remains that any group crossing over into the secular market faces a predictable din of criticism that it has “gone secular.”

Jars of Clay also has been criticized, although there is no evidence the band has soft-pedaled its theology to appeal to the secular market. “It can start to get to you when people ask over and over again, ‘Are you going secular?’ ” Mason said wearily. “Well, what do you define as secular? Do we want to reach unchurched people? Of course. And we’re not going to hide what we believe to do that. But the greater our reach becomes, the more suspect our faith and commitment in the eyes of some people. It’s like ‘either you’re in or you’re out.’ There’s got to be a third rail where music can just be music. And in the end there’s really nothing we can do but be who we are.”

During its visit to Nashville, Jars of Clay was on a brief hiatus from the recording sessions for its third album, If I Left the Zoo, scheduled for release this month. “We don’t know what it’s going to be yet,” one member confessed, although Haseltine expressed the cautious hope that the album would contain “lyrical moments that will set new benchmarks” for the group. Indeed, I had heard from several sources that the album’s producer was pushing the musicians hard, and they all agreed. In Jars of Clay’s previous efforts some of the best work has come in the studio, where a riff or an improvisation sparks a burst of creativity.

How does the creative process work for Jars of Clay? “Dan keeps a journal,” Stephen Mason explained, referring to Haseltine, the lead singer. “Then we’ll start a riff on a guitar, and it emerges from there.” Haseltine is diffident and self-effacing, often averting his eyes as he gathers his thoughts. “I never know what I’m writing until a couple of years later,” he said. “God is the one who’s working, pushing the pen a bit.” When I suggested to Haseltine that he was “something of a mystic,” he looked confused, clearly wanting me to define the term. I suggested that a mystic was someone with an almost intuitive grasp of God and spirituality. Haseltine, with characteristic modesty, demurred. “No, I wouldn’t say that I have any grasp at all. I prove that every day.”

I tried another tack, floating the names of John Donne and George Herbert or T. S. Eliot as possible sources of inspiration. Once again I had to explain the references. Haseltine shrugged and shook his head, suggesting that his real inspiration lay in the old hymns. “Hymns are the closest thing to poetry that I read,” he said, somewhat apologetically. “I use them as a foundation for what I write.” He looked away. “I think what gets us is the magnificence of God and how puny and wretched we are. Nothing does that like a good hymn.”

Dusk has finally descended on Chautauqua. The group sings “Oh, sweet Jesus, you never let me go,” while the audience again sways to the music, arms upraised. A woman in her early twenties, eyes closed, performs a kind of willowy dance. Stars have punched a million holes into the summer sky, and the concert is winding down. “When you look at the depravity of man and the brilliance of God and the gap in between, we decided to write a song about it,” Haseltine announces. “Being the creative bunch that we are, we called it ‘Hymn.’ ” It opens with just a few spare notes on an acoustic guitar.

Oh refuge of my hardened heart

Oh fast pursuing lover come

As angels dance ’round Your throne

My life by captured fare You own

Not silhouette of trodden faith

Nor death shall not my steps be guide

I’ll pirouette upon my grave

For in Your path I’ll run and hide

The crowd rises, arms outstretched, responding, perhaps unconsciously, to the resurrection motif. The man with cotton in his ears has long since left. “We like to close our concerts with ‘Hymn,’ ” Mason told me in Nashville, “because it takes the focus off of us.”

Oh gaze of love so melt my pride

That I may in Your house but kneel

And in my brokenness to cry

Spring worship unto Thee

The lyrics evoke the poetry of Herbert or Donne or Rainer Maria Rilke, more elegy than anthem.

When beauty breaks the spell of pain

The bludgeoned heart shall burst in vain

But not when love be ‘pointed king

And truth shall Thee forever reign

Sweet Jesus carry me away

From cold of night, and dust of day

In ragged hour or salt worn eye

Be my desire, my well spring lye

A slight chill blows off the lake, and it’s time to head back into the night. Only the benediction remains:

Oh gaze of love so melt my pride

That I may in Your house but kneel

And in my brokenness to cry

Spring worship unto Thee

Spring worship unto Thee

Spring worship unto Thee.

Amen.

Randall Balmer is Ann Whitney Olin professor of American religion at Barnard College, Columbia University in New York City.

Copyright © 1999 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.