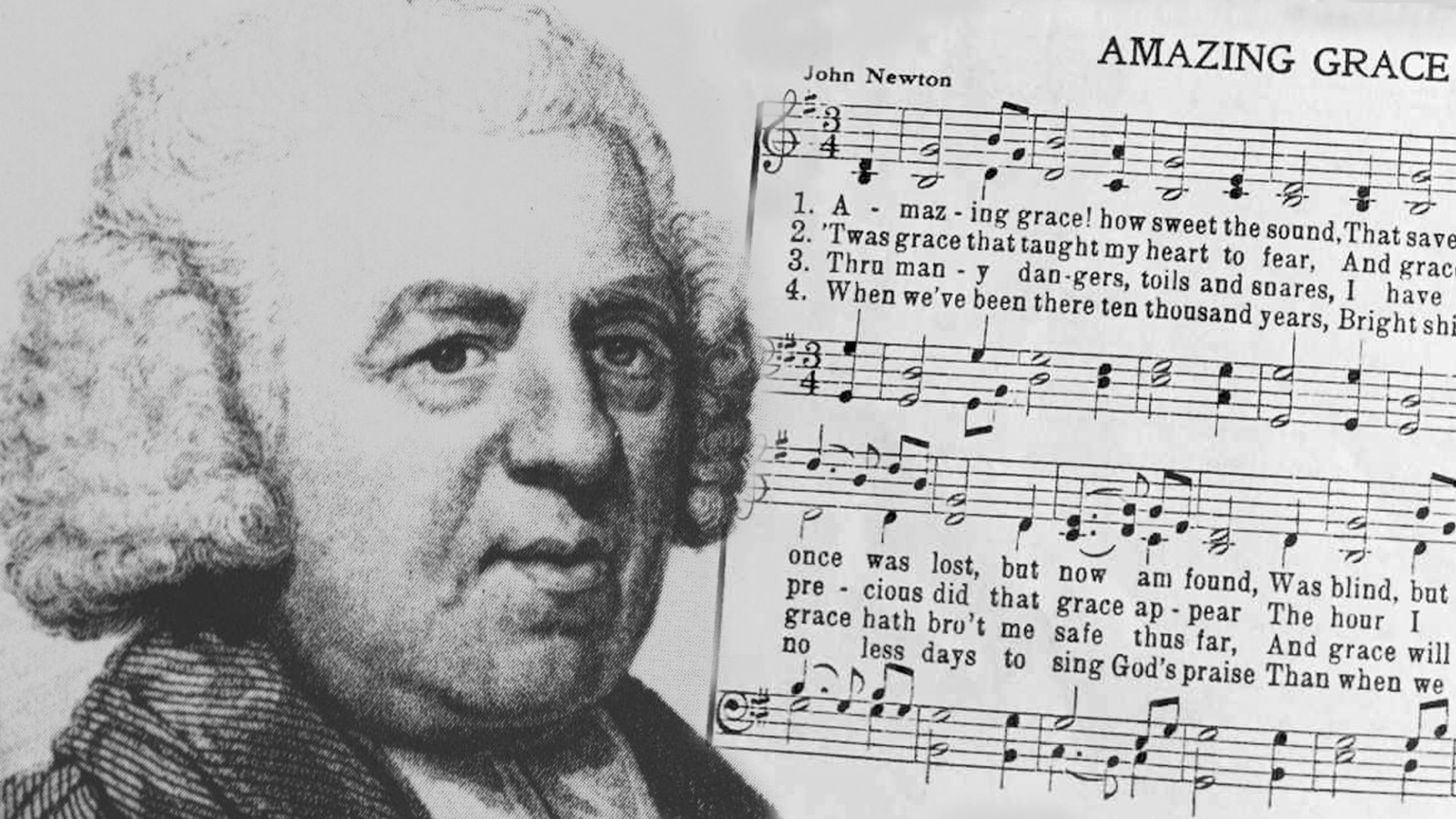

Amazing Grace: The Story of America's Most Beloved Song Steve Turner Ecco, 288 pages, $23.95

John Newton, the author of "Amazing Grace" and "Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken," was remarkably thickheaded. If Calvinists believe in the "perseverance of the saints," this future Calvinist devoted himself to demonstrating the persistence of the sinner. The first few chapters of Steve Turner's engaging Amazing Grace chronicle Newton's dogged commitment to self-destructive vice to the point that this reader could not help scrawling in the margin of page 37, "This man was thick!"

Like many a seafaring man of the 18th century, Newton repeatedly engaged in physically and spiritually destructive behaviors. He deserted the Royal Navy, then was flogged for desertion and demoted. He made up disrespectful songs about his ship's captain and was demoted again. He frequently drowned himself in drink. He prided himself in creative profanity and sharp attacks on Christian belief. Even though on several occasions he seemed to have been miraculously preserved when he should have lost his life, he persisted in the godless philosophy he learned from the Third Earl of Shaftesbury's Characteristicks (which book Alexander Pope said had "done more harm to Revealed Religion in England than all the works of Infidelity put together"). He hardened his heart against God's advances.

One definition of neurosis (variously attributed to figures ranging from Rudyard Kipling to Bill Clinton) is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. Though his stupid persistence might qualify him for that label and worse, Newton was not just neurotic, he was spiritually sick. And God let that sickness run its course until Newton was willing to be healed.

The story of his conversion during an Atlantic storm is well known, and Turner tells it with exceptional drama. He seizes the moment to offer readers a lesson in what Wesley called experimental religion. "Still at the [ship's] wheel he reasoned that the best way forward was to ask for the power of the Spirit and then to start acting as though the gospel was true. The proof would be in the living."

The proof indeed came in the living, and Turner goes on to tell the story of a man devoted to God, to the people of his parish, and to the woman he loved. Indeed, his early persistence in vice was matched only by the perseverance of his romantic longings for Mary Catlett, whom he eventually married.

Parish poet

What emerges from Turner's book is the picture of a man deeply devoted to teaching the gospel to the people of Olney parish. He was also devoted to the spiritual and emotional welfare of his depressive friend, poet William Cowper. With Cowper, he produced an amazing body of hymnody, revolutionary for its time. Vibrant hymn singing was one of the earmarks of the 18th-century evangelical revival, but because of liturgical restrictions, the popular hymns were forced out of the confines of the church's Sunday worship into less formal gatherings outside consecrated buildings. In the Olney parish, this meant extra meetings in the vicarage on Tuesdays and Thursdays, and on Sundays after church. The hymns that Newton and Cowper wrote seem formal and didactic by today's standards, but in their time they were marked by a simplicity of language and straightforwardness of meaning designed to be sung by laborers and other "plain people."

Often Newton wrote hymns to match the biblical passage from which he was planning to teach. One of these hymns was "Amazing Grace," and we can date the composition of the hymn because we know the text (1 Chron. 17:16-17) and the day he preached on it (Jan. 1, 1773). The passage records King David's response to God's promise to make his name like the greatest men of the earth. "Who am I . . . that thou hast brought me hitherto?" Turner recounts the main points of Newton's exposition of the passage and shows how the verses of "Amazing Grace" reinforce Newton's pastoral teaching.

Turner has much more to say about Newton, but his not-to-be-missed point is this: Newton's conversion did not bring him immediately to see the evils of slavery. Morally speaking, he was a slow learner. Turner remarks on the irony of the tenderness of this ship captain's letters home to his beloved Mary while he showed complete lack of concern for the African families he was breaking up. A telling passage from one letter cites "the three greatest blessings of which human nature is capable" as "religion, liberty, and love." But referring to those he had helped to enslave, he wrote, "I believe . . . that they have no words among them expressive of these engaging ideas: from whence I infer that the ideas themselves have no place in their minds," as if blacks are not human!

Though such moral blindness is obvious to us, it was hardly unusual among devout Christians of his time. And when in God's Providence it came time for Newton to take a stand, it was again through ironic agency. Newton met William Wilberforce when the future politician was a very rich orphan eight years of age. The two struck up a spiritual friendship, and when as a young man Wilberforce had a spiritual awakening, he sought out Newton, like Nicodemus under cover of night. It was Newton who moved Wilberforce to apply his Christian principles to his politics. But when it came to denouncing the slave trade, Newton would not commit himself publicly until the mid-1780s—nearly 30 years after the issue was first broached in Parliament, 20 years after the Countess of Huntingdon began campaigning for equal treatment of the races, and 14 years after John Wesley wrote his Thoughts on Slavery. Turner argues that it was Wilberforce who finally got Newton to go public with his concerns about the slave trade. The mentee challenged the mentor to consistent Christian principle.

Wedded to a perfect tune

For all its fascinating detail about John Newton, Turner's book is really about "Amazing Grace." And here the book provides additional history that is otherwise hard to find.

First, it details the background of the hymn's most familiar tune. If your denomination's hymnal was published before 1991, chances are it improperly credits the tune to James Carrell and David Clayton's shaped-note songbook Virginia Harmony (1831). But Turner details the sleuthing done by Anglican hymnologist Marion Hatchett, whose 1991 essay revealed that two earlier forms of the tune were published in Charles Spilman and Benjamin Shaw's Columbian Harmony (1829). It remained, however, for William Walker's Southern Harmony (1835) to marry Newton's text to the tune Americans grew to love. Turner praises Walker's choice as "real genius" and "a marriage made in heaven." Turner cannot restrain his enthusiasm: "It was as though the tune had been written with these words in mind. "The music behind 'amazing' had a sense of awe to it. The music behind 'grace' sounded graceful. There was a rise to the point of confession, as though the author was stepping out into the open and making a bold declaration, but a corresponding fall when admitting his blindness."

The credit goes to Southern Harmony for much of the early popularity of this hymn. The book sold 800,000 copies in a time when the U.S. population was just over 23 million. And Southern Harmony's marriage of tune and text influenced in turn the compilers of The Sacred Harp (1844), which became the most influential tune book in the rural South's shape-note singing movement.

The hymn moved from South to North and from agricultural to industrialized settings when Ira D. Sankey, evangelist Dwight L. Moody's popular songleader, included it in his songbooks. Sankey used three different tunes, none of them New Britain.

The definitive moment came about 1900 when Chicago hymnwriter and publisher Edwin Othello Excell refined the tune and muted the theology. Excell moved the music a long way from its shape-note roots and made it acceptable to America's emerging middle class. He also dropped Newton's final lines and substituted a quatrain from the hymn "Jerusalem, My Happy Home"—the now familiar "10,000 years" verse. Harriet Beecher Stowe had added that verse to Newton's text in Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852), but until Excell substituted it, it had not appeared in a hymnbook as part of "Amazing Grace." American religious culture had shifted from the Calvinism of Jonathan Edwards and the First Great Awakening to the Arminianism of Dwight Moody and Charles Finney. The emphasis was no longer on God choosing people, but on people choosing God. And the substitution of that final verse made the hymn less likely to offend the new sensibilities.

Excell's updating of Newton was a key step in the gradual transmogrification of the hymn into a self-help anthem. Seventy years later, when folksingers like Judy Collins, Joan Baez, and Arlo Guthrie were popularizing the hymn in secular circles, the human potential movement was in full flower. With the words God and Lord missing from the most common versions of the text, there was nothing to keep the new generation from treating grace as a term for the way life seems to heal and reward those who pick themselves up and try again.

Turner devotes a chapter titled "Into the Charts" to the history of the song's popularity in the latter third of the 20th century. He also appends a fine discography for those who want to track down the most important recordings. The most significant part of "Into the Charts" is his comparison of Judy Collins's simple a cappella folk recording with Aretha Franklin's gospel rendition.

One night in New York, Collins was in an encounter group where the rage was getting out of hand. To calm the group's members, she began to sing the song she had knew from her Methodist childhood. "Amazing Grace" had its desired effect, and her producer, who was part of the group, urged her to include it on her next album. Thus was Judy Collins's interpretation of the song born out of the human potential movement.

On another night in Watts, soul singer Aretha Franklin returned to her gospel roots to record an album live at the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church. Whereas Judy Collins took four minutes and four seconds to sing four stanzas and repeat the first verse, Aretha took 14 minutes to wring every ounce of meaning and experience out of just two verses. Turner comments: "Aretha's version went back . . . to the long meter style of the Holiness churches where the tune is pulled apart wide enough to let the spirit in. . . . In gospel music the point is not clarity, precision, and faithfulness to the text but witness to personal experience and faithfulness to the movement of the spirit."

Throughout the book Turner takes opportunities to give mini theology lessons: on the difference between Calvinists and Arminians, on the differences between Catholic and Protestant notions of grace, on experimental religion, and on the progressive nature of the Christian's growth in holiness. None of this is gratuitous, but is the essential framework for understanding the hymn.

Joan Baez told Turner that she didn't understand why anyone would think of "Amazing Grace" as a religious song. If anyone takes the time to read Turner's book, they will be well on the way to recapturing the God-centered vision of John Newton and the spirit-led experience of Aretha Franklin and the shape-note singers.

• • •

Next month: What the early Christians really thought about Jesus' resurrection.

Copyright © 2003 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Amazing Grace: The Story of America's Most Beloved Song by Steve Turner is this month's selection for the Christianity Today Editor's Bookshelf. Elsewhere on our site, you can:

Read our extended interview with author Steve Turner