It has been 25 years since Alzheimer’s began taking hold of Muriel McQuilkin, wife of Robertson McQuilkin, president of Columbia Bible College and its graduate school. As the disease progressed, in 1990, McQuilkin resigned to care for his wife full time. She stopped recognizing him in 1993. At Christianity Today‘s invitation, McQuilkin wrote two articles about his decision and caring for his wife (“Living by Vows,” CT, October 8, 1990, and “Muriel’s Blessing,” CT, Feb. 5, 1996. On September 20, 2003, Muriel McQuilkin died at the age of 81.

Stan Guthrie, CT’s associate news editor, was a graduate student at the school when McQuilkin announced his resignation. Guthrie interviewed McQuilkin, 76, shortly after Muriel’s death.

What was your daily routine like, especially toward the end?

I would fix breakfast and then go in and turn on the lights, and she would awaken, although in the last year or two she didn’t open her eyes much. Usually in the morning she would open her eyes and then I would feed her. And then of course, after that I had to change and clean her up. If it was nice weather, I would put her in the wheel chair and take her out into the yard for her to sit out there for two or three or four hours. Then lunch. She had to be changed every four hours.

She had excellent health, so I usually had about six hours a day of quiet to do my own writing and business and so forth.

In the evening we would again have supper, and after supper about 9:00 I’d start working on the bedtime routine.

But last summer she began to choke on the food.

It must have been difficult to care for her at that level, almost as if she were a newborn again.

Well, she was not burdensome. She was always lovable and accepted my ministrations, for the most part. She was low maintenance.

Some people sort of resent the imposition, but those thoughts never came to me. I thought it was a privilege to care for her. She had always cared for me. So it was not a burden. In fact, if it had been a burden, maybe there wouldn’t be so much grief now, that sense of loss.

I assume you were even grieving while she was alive. Did that process take away any of the grieving that you’re feeling now?

I don’t see how I could have any more grief. Actually, 25 years, that is so gradual, so incremental that there wasn’t time to think about [grieving her loss]. My memories were all happy memories. I’d review them to her as long as she had any consciousness. I really even chatted to her after she wasn’t aware of anything.

My children, who all live at a distance, all said that they grieved her loss way back at the beginning, when she no longer knew them. But I never went through that kind of process.

How aware of you was she?

She lost that 10 years ago.

What surprised you during the time of caring for her?

Everything. You don’t know what’s coming next, but you’re not surprised that something is next. I didn’t try to predict whether when she died I was going to greatly grieve or I wasn’t going to greatly grieve or whether I was going to feel this or that.I still don’t know what I feel. The churning of emotions, just grief, is all I can call it.

What did this experience teach you about the Christian life? You’ve written a book on Christian ethics and have had to apply a lot of it.

Since I’ve tried to base my life on bringing my choices under the authority of Scripture, and I made the decision early on that it was non-negotiable, I didn’t really have struggles about what to do. As I told the students when I resigned from school, this was one of the easiest decisions I ever made.

But did I learn things? Yes. For example, one day I was ministering to [Muriel], taking care of her, and I said, “Honey, you’re the luckiest girl on earth. You don’t have a worry in the world. You don’t have anything to plan; everything is provided for you. Why, you don’t even have any guilt; you don’t have any sin to repent of.”

Then I thought about [the fact that] I loved her but she can’t love me back. For some years after she went to bed, in the morning our eyes would connect briefly, I mean really connect. She was aware of my presence, and she’d gaze at me and smile. Her trademark, of course, during her life, was her laugh, her smile. And when she did, I would fly a flag out front because I wanted my friends and neighbors to know this is a smile day. But then in the last three or four years, there weren’t any smile days.

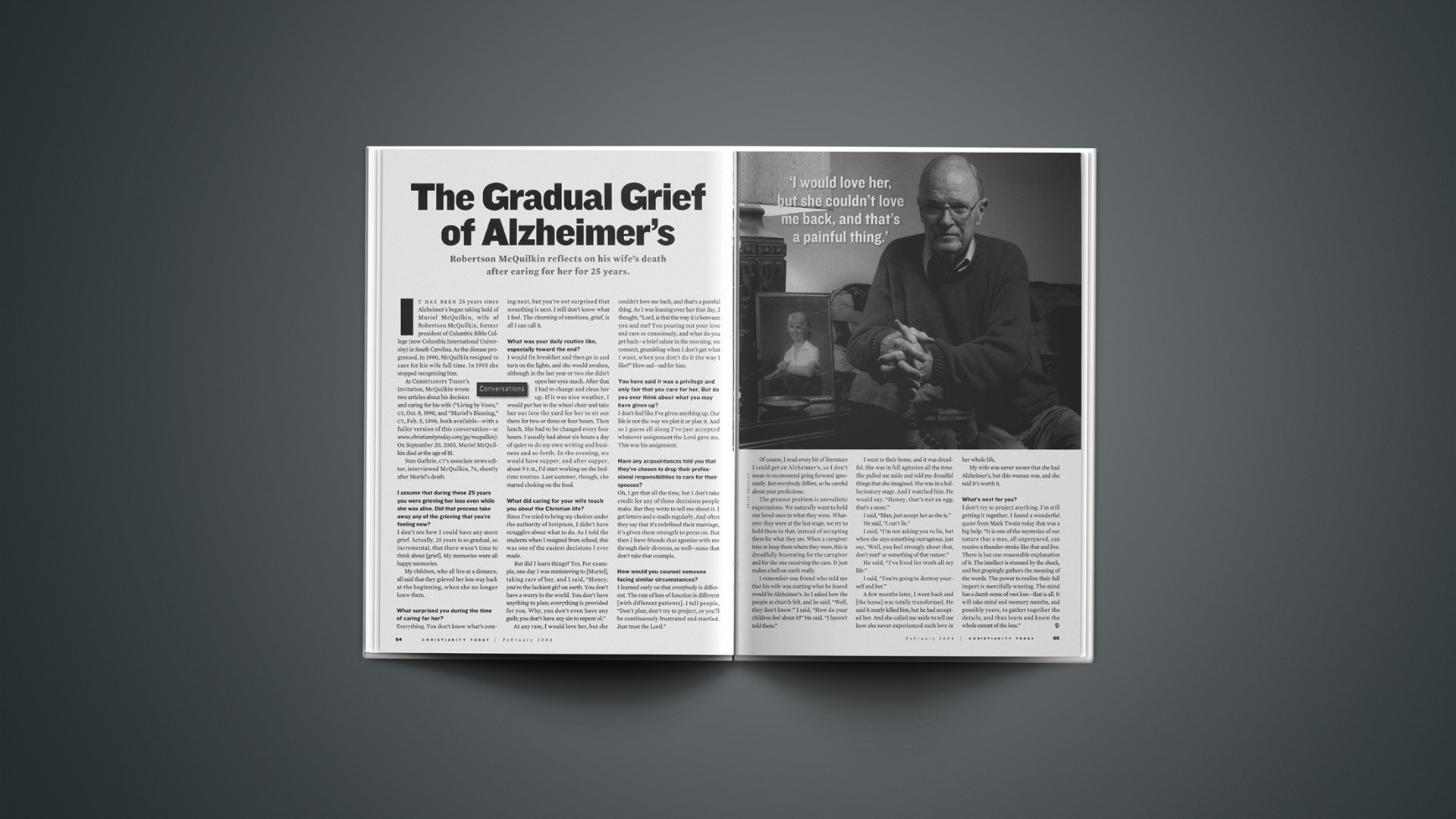

At any rate, I would love her, but she couldn’t love me back, and that’s a painful thing. As I was leaning over her that day, I thought, “Lord, is that the way it is between you and me? You pouring out your love and care so consciously, and what do you get back—a brief salute in the morning, we connect, grumbling when I don’t get what I want, when you don’t do it the way I like?” How sad—sad for him.

Obviously, you have said it was a privilege and only fair that you care for her. But do you ever think about what you may have given up to care for her?

I don’t feel like I’ve given anything up. Our life is not the way we plot it or plan it. And so I guess all along I’ve just accepted whatever assignment the Lord gave me. This was his assignment. I know I’m not supposed to have that kind of reaction, but you asked me, and I have to be honest.

I often tell the story of how early on, about two years after I resigned, a young couple came out [to visit], and the man said, “Do you miss being president?” And I said, “You know, I never thought about it. But now that you asked, no, I don’t. I enjoy my assignment. I like learning how to cook and garden and keep house, and taking care of my beloved.” At that time she was still responding to loving care.

But that night, after I went to bed, I thought, “Lord, I never asked you why. I’m apt to ask you, ‘Why not me?’ Everybody is suffering; everybody has loss and heartache. It’s part of our human, fallen condition. So you know I don’t ask why. It’s your business; you’re the one in charge. But, if a coach puts his player on the bench, he must not need him in the game. And you don’t have to tell me why you don’t need me in the game. But sometime, if you’d like to, I’d much appreciate it.”

So I went on to sleep. The next day, [Muriel] was still walking sort of wobbly, and we went out for our walk around the block. I’d have to hold her hand to balance her.I heard this shuffling behind me. I looked back and here’s a local derelict. He looked us up and down. And then he said, “Tha’s good—tha’s real good. I like that.” And then he wandered off, mumbling, “Tha’s so good.” And I chuckled.

When we got back to the garden and sat down, all of a sudden, it hit me. I said, “Lord could you speak to me through a half-inebriated voice of an old derelict? You did, and if you say it’s good, that’s all I needed to hear.”

So I had that assurance all along, that this was my assignment and was pleasing to him.

Have any others told you that they’ve chosen to drop their professional responsibilities to care for their spouses?

Oh, I get that all the time.I don’t take credit for any of those decisions people make. But they write to tell me about it.

How would you counsel someone facing similar circumstances?

I learned early on that everybody is different. The rate of loss of function is totally different [with different patients]. I tell people, “Don’t try to predict.” When Muriel was first diagnosed, my doctor gave me a medical journal article that said it was seven years average life span, from diagnosis to death. So I planned accordingly. Now I tell people, “Don’t plan, don’t try to project, or you’ll just be continuously frustrated and startled. Just trust the Lord.”

Of course, I read every bit of literature I can get on Alzheimer’s, so I don’t mean to go forward ignorantly. [But] everybody differs, so be careful about your predictions.

The greatest problem is unrealistic expectations. We naturally want to hold our loved ones to what they were. Whatever they were at the last stage, we try to hold them to that, instead of accepting them for what they are. When a caregiver tries to keep them where they were, this is dreadfully frustrating for the caregiver and for the one receiving the care. It just makes a hell on earth really.

I never went to a support group. I had enough of my own burdens without taking on everybody else’s. Sometimes I have accepted an invitation to speak at one of these [groups.] A lot of angry people. They’re angry at God for letting this happen—”Why me?” They’re angry at the one they care for, and then they feel guilty about it because they can’t explain why they’re angry at them, but they are. And they’re angry at themselves. Just terrible frustration. So I say, in acceptance there’s peace.

I remember this one friend who told me that his wife was starting what he feared would be Alzheimer’s. So I asked how the people at church felt, and he said, “Well, they don’t know.” I said, “How do your children feel about it?” He said, “I haven’t told them.”

I went to their home, and it was dreadful. She was in full agitation all the time. She pulled me aside and told me dreadful things that she imagined, made up. She was in a hallucinatory stage. And I watched him. He would say, “Honey, that’s not an egg; that’s a stone.”

I said, “Man, just accept her as she is.” He said, “I can’t lie.” I said, “I’m not asking you to lie, but when she says something outrageous, just say, ‘Well, you feel strongly about that, don’t you?’ or something of that nature.” He said, “I’ve lived for truth all my life.” I said, “You’re going to destroy yourself and her.”

A few months later, I went back and [the home] was totally transformed. He said it nearly killed him, but he had accepted her. And she called me aside to tell me how she never experienced such love in her whole life.

My wife was never aware that she had Alzheimer’s, but this woman was, and she said it’s worth it.

Accept them as they are. Don’t try to change them or hold them back to what they used to be.

What’s next for you?

I don’t try to project anything. I’m still getting it together. I found a wonderful quote from Mark Twain today that was a big help: “It is one of the mysteries of our nature that a man, all unprepared, can receive a thunder-stroke like that and live. There is but one reasonable explanation of it. The intellect is stunned by the shock, and but gropingly gathers the meaning of the words. The power to realize their full import is mercifully wanting. The mind has a dumb sense of vast loss—that is all. It will take mind and memory months, and possibly years, to gather together the details, and thus learn and know the whole extent of the loss.”

Copyright © 2004 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Also posted today

CT Classic: Living by Vows | As his wife suffered with Alzheimer’s, Robertson McQuilkin said, “If I took care of her for 40 years, I would never be out of her debt.”

CT Classic: Muriel’s Blessing | Despite the toll of his wife’s Alzheimer’s, a husband marvels at the mystery of love.