At dusk on a chilly October day, I get on the metro train at Oberkampf, a trendy street on the east side of Paris. A mustached man in his 40s sits in front of me, sets his briefcase down, pulls out a yellow brochure from his jacket, and begins to read it.

"Scientific Proof" says the arguably apt title in French. I know what's inside—an argument that humans' meticulous design points to the existence of a loving God; and that he wants us to live in union with him for eternity. If the reader wants to know more, he can fill out a contact form and send it to Jews for Jesus.

I wait for the commuter to do something stereotypically French, like crumple the pamphlet and cuss. But he studies it for about five minutes, which allows for a slow and thorough read. He sighs, and for a while appears to be deep in thought. He then folds the brochure and puts it in his pocket.

I don't pretend to know this man's religious background, but to me his curiosity represents a renewed openness to the gospel in France.

At the beginning of the 21st century, the postmodern French have deconstructed deconstructionism, seen through the utopia of socialism, and realized that wine and other sensual delights only go so far in filling what French philosopher Blaise Pascal described as the "God-shaped void." According to France Mission, an opinion poll conducted in March 2003 showed that 32 percent of those who call themselves Christians have recently returned to the faith. In 1994, only 13 percent said so.

You see this trend in the writings of French intellectuals and philosophers who are products of the 1960s sexual revolution when "it was forbidden to forbid," says Mark Farmer, former pastor of a Baptist church across from the Louvre. The most articulate plea for France to re-examine its Judeo-Christian roots came recently in Jean-Claude Guillebaud's critically acclaimed Re-founding the World: The Western Testament.

"What's this? A French intellectual starting his book with a quote from Psalm 1?" Farmer recalls his reaction to first paging through the volume. "And he's got a chapter on the apostle Paul? He starts the book by saying that the 20th century has been a century of disillusion. Marxism, evolution, socialism, hedonism, wars have all failed us. He says it's easy to be pessimistic, but there are some things that we appreciate about our civilization. For example, the notion of right and wrong that transcends any culture—where does that come from? He stops short of saying that he himself has become a Christian, but he's led the horses to the water."

The sales of another book—the Bible—are at a historic high, according to the French Bible Society. In 2003—which Christians promoted as the Year of the Bible—FBS's publishing house sold an unprecedented 100,000 Bibles and 50,000 New Testaments, says Christian Bonnet, the group's secretary general. At the time of our conversation, the Bible with life application notes for seekers, La Bible Expliquée, had just sold a record 80,000 copies in one month. In the last 15 years, Bonnet says, secular bookstores, "which never wanted to sell Bibles before," and major supermarket chains began selling Bibles.

The search for God in the most secular country of Europe is so universally felt that even a business journal—the equivalent of Forbes or Fortune—was compelled to publish a special issue in July and August of 2003 whose cover exclaimed, "God, the Stocks Are Rising!" Its 72 pages describe the surge of interest in religion and its effect on the business world, says Paris-based International Teams missionary Steve Thrall. The contents page announces that "after a materialistic 20th century, religions are coming back in force. In France, this rise in spirituality is pushing out secularism in both schools and business."

The accelerated growth of Islam in France, to nearly 5 million adherents now, has rightly received much attention from the American media. But few people realize that French evangelicals have experienced healthy—sevenfold!—growth since 1950, and that evangelistic influences such as the Alpha course are revitalizing faith in the nominally Catholic and practically secular nation.

Worse Than a New Boyfriend

While walking in a park near the Eiffel Tower, I am reminded of the context for this growth as I stumble upon a small Temple of Human Rights. Covered with Egyptian hieroglyphs and Freemasonry symbols, it stands for France's only politically correct religion—the belief in human rights. France's reputation as brazenly secularist, oversexed, and mostly oblivious to the gospel is deserved. It wasn't in vain that Jules Ferry, an active Freemason, founded the public school system in 1881 "in such a way as to inoculate the minds of kids against Christianity," Farmer says. (When the French public found out that a Ferry descendant, the recent minister of education Luc Ferry, sent his daughters to a Catholic school, it caused quite a stir.) As papal biographer George Weigel shows in The Cube and the Cathedral: Europe, America, and Politics Without God (to be published by Basic Books this April), the conspicuous omission in the E.U. constitution of the continent's Christian roots is yet another denial of the faith that made its democracies possible. Many missionaries have returned from France in dismay, after seeing few or no converts.

And yet, an evangelical congregation has been born here every 11 days in the last 35 years, according to the conservative estimates of Daniel Liechti, a respected tracker of evangelical growth in France who heads development at France Mission. This statistic is based on the net total, one that takes into account the churches that die out. The number of evangelicals has increased from 50,000 to at least 350,000 since 1950. Turns out all these missionaries who returned from France in dismay did accomplish something besides learning how to pick a wine that goes with duck à l'orange! "A good slice of this growth should be credited to American and European missionary help," says Nogent Bible Institute's lecturer in practical theology André Pownall. But "the stereotype some secular observers of religion in France are too happy to spread"—that evangelicals are a U.S. import—is wrong, says Sebastien Fath, researcher of evangelicalism at the National Center for Scientific Research at the Sorbonne. That would leave out the great contribution of the French Pentecostals, who are effective evangelists. "There were none of them before 1930," he says. "There are 200,000 now."

Religious conversions still befuddle the French. David Brown, the head of the French equivalent of InterVarsity, University Bible Groups, told me about one girl's experience. Her father is a militant left-wing activist; he and his wife are separated. When he found out that his daughter joined Brown's church and left with the youth group for a weekend in Normandy, he became enraged and came to see Brown. These were his words: "Here I thought that she was just going off for a weekend with a new boyfriend! But then I find out it was to read the Bible!"

"To go off with a new boyfriend is no problem," Brown says, "but to read the Bible is unacceptable." The father was also concerned that his daughter had become too religious. "I'll prove it to you," he told Brown. "She's got a Bible by her bedside!"

Brown says, "A lot of French people think like him."

Of France's 60 million inhabitants, about 40 million consider themselves Catholic, but only about 5 million attend church each month. Up to 5 million are Muslim and 650,000 are Jewish. One million are Protestants; about 650,000 of them belong to the often austere and liturgical Reformed and Lutheran churches, but only a small proportion attend church regularly. Up to one-third of these mainline church attenders are likely evangelical-minded. Finally there are the 350,000 evangelical churchgoers. Most French are then deists, agnostics, or atheists. Or seekers.

Laïcité is the nearly sacred principle guarding the separation of church and state in France. It means that all religious groups are free and the state will not meddle in any of them. It's mostly good news to evangelicals, who no longer have to fear that their pastors will be thrown in jail for their beliefs, as was sometimes the case before 1905. But laïcité also means that the state neither recognizes theological degrees nor subsidizes those who pursue them. "For example, the Catholic Institute of Paris gives out doctorates that would be recognized by most states in the world except France," says UPI's religious affairs editor Uwe Siemon-Netto, who lives in France.

The year 2004 was officially declared the Year of Laïcité, which worried some evangelicals. "The catalyst is Islam, and the hardening of attitudes in the fundamentalist wing as they attempt to use veiled schoolgirls to claim greater rights for Islam in France," Brown says. Fath believes officials "overemphasized the need for a neutral space in public schools" by banning the headscarves. But "this move is not a threat to evangelicals, who have never displayed offensive religious symbols in public schools."

More troubling is the declaration presidents of French universities released last September to bar religious activity at universities. "One reason for that—and it's awfully controversial to say so—is that Islamic activists have been active in the university," Brown says. "They demanded that they should be able to lay out their prayer mats during examinations, for example. Or they refused to take an oral exam with a female professor." The schools seem to have overreacted to these agitations by limiting the freedom of expression of those who do not violate the principles of democracy. As a result, University Bible Groups finds it harder to meet on university campuses.

There is an uncanny exception to France's ostentatious separation of church and state. In the northeast area of the country—two and a half counties worth—the state and church are joined, especially at the pocket. Europe's most secular government picks and pays pastors, priests, bishops, and seminary professors, and builds churches associated with officially recognized denominations. The reason is that the Alsace region and the adjacent parts of Lorraine were annexed to Germany between 1870 and 1918 and thus missed out on the 1905 disestablishment, when the state broke links with religion. After returning to France, the churches in these counties were never disestablished. Aside from the state-recognized Catholic, Reformed, and Lutheran congregations, there are a lot of Evangelical Free churches there today, says Pownall. They do not get persecuted, as sometimes used to be the case, "but they are often suspected of being cults." The majority of Christians in the two and a half counties still don't want to break up with the state because the ministers make a decent living on taxpayers' money, unlike their colleagues in the remainder of the country.

Outside of schools, evangelicals have no problem conducting evangelism once they've secured necessary permissions. In most cases, any opposition is due to the legal ignorance of local authorities. Une Bible par Foyer has "with perseverance and determination, wrung from the Paris authorities permission to hold Bible stalls in markets and on street corners," says Pownall. "But they carry the official permit with them, as occasionally an overzealous police squad will question their right to be there." A police chief ended up apologizing to Jews for Jesus, admitting he hadn't known the law, after his officers made the evangelists throw their tracts into trash bins.

Evangelical Catholics

When we met at Liechti's Paris office last October, he said there were 1,850 evangelical churches in France; in 1970 there were only 760 (see the maps below).

These are the groups that meet Liechti's cautious definition of a church: a place that holds worship services three Sundays a month. "To this number, you could easily add 800 to 1,000 churches," Liechti says—if you count the congregations that meet less than three times a month and the informal congregations that mainly consist of new immigrants but that are vibrant nevertheless. "God knows them, but we cannot count them," he says.

Henri Blocher, a well-known evangelical church leader who teaches at an evangelical seminary in Vaux-sur-Seine and heads a new doctoral program at Wheaton College, believes this growth is sound. "I visit a number of churches where I meet many people in their 30s, families with children, committed and balanced, with an interest in Christian truth," he says. "This is what I call healthy." People in their teens, 20s, and 30s are the generation who reject the cynicism of their socialist parents. They are Europe's Christian hope. Theirs are the faces I saw in 1993 in Taizé, a French ecumenical community near Lyon where hundreds of thousands of young Europeans lose themselves in simple worship.

The resurgence of evangelicalism was first noticeable when, as the Catholic Church was closing seminaries, evangelicals were opening them: a Bible college was started in Nogent-sur-Marne in 1921, the Free Seminary of Evangelical Theology in Vaux-sur-Seine opened its doors in 1965, and the Free Reformed Theology Seminary at Aix-en-Provence in 1974. Soon, French society was "surprised to discover that, for instance, in a city like Montpellier there are four times more evangelical assemblies than Reformed ones," Fath writes. "And in dozens of French cities, the only French Protestant churches are evangelical."

The climate of secularization has made allies of evangelicals and gospel-focused Catholics, as well as Reformed and Lutheran Christians. They joined together in organizing well-attended Bible exhibits in 2003 as part of the Year of the Bible. The Archbishop of Paris, Jean-Marie Cardinal Lustiger, has said two good things that Catholics have received from the Protestants are the charismatic movement and the Alpha course.

In many ornate Catholic churches, including Notre Dame de Paris, big posters advertise the Alpha course, which is booming in Catholic parishes. In 1998, the number of French groups studying the principles of Christianity through this explicitly evangelistic program was 5. In 2004, it was 303.

Add to this the surprise that Jews for Jesus' Gordon experienced as he handed out his brochures: "I'm shocked by how many born-again Catholics I've run into—probably 20—who say, 'I was raised Catholic but then gave my life to Jesus.' I even run into Catholics who are giving out invitations to their churches."

The number of Catholic priests in France shrank from about 50,000 in 1970 to around 25,000 in 2000, and most of them are elderly. But there's an upside to this decline.

"Many congregations are being led by laypeople, chiefly women," Siemon-Netto says. "They hold worship services that are Protestant in many ways, preaching gospel-centered sermons, and distributing hosts consecrated, of course, by a priest in a neighboring community." With many priests having to look after up to 50 altars, laypeople also conduct funerals, and an increasing number of Catholics support the ordination of women and the end of mandatory celibacy.

Catholics don't mind borrowing evangelical teachers, either. Some Catholic secondary schools hire evangelicals to teach religion classes. Neal Blough, a professor of church history at Vaux, teaches history of the Reformation at the Catholic Institute of Paris and a Jesuit seminary. "The tendency is toward an opening," says Louis Schweitzer, professor of ethics and spirituality at Vaux, who used to head the ecumenism center at the Catholic university. "On ethical issues such as abortion and bioethics, Catholics are nearer to evangelicals than to the Reformed and Lutherans."

In turn, the Africans, along with other immigrants and their children, are energizing French Christianity. The face of French evangelicalism is multicultural, replicating "the great ethnic diversity displayed by the French soccer team who won the 1998 World Cup," Fath says.

Heavenly mix

Just look at the members of the Christian and Missionary Alliance church Eglise Protestante Evangélique, located in a storefront in La Défense, a progressive business suburb of Paris. Last October, wearing a tie with international flags, pastor Jean-Christophe Bieselaar began the service by reading a passage in Revelation that describes all nations worshiping the Lord. This heavenly diversity marks the congregation.

When Bieselaar asked how many among those attending are indigenous, Caucasian French, only ten people raised their hands. Forty are African immigrants—some naturalized, some legal, and some illegal. When he asked them to say the names of their motherlands aloud, they mentioned Gabon, Ivory Coast, Congo, South Africa, Togo, Nigeria. Several are from Asia: Indonesia, Vietnam, Cambodia, China, Japan. Several are from Iran. Two are from Canada; a couple from the States. Some are from Colombia, Brazil, England, Spain.

Most of the churchgoers belong to the lower middle class, especially the African immigrants. Some are students, some engineers, some executives. Among them is a Caucasian French woman named Laurence, 34, who ministers to Iranian immigrants. As is the case with many French people, her nominal Catholic faith didn't keep her from consulting fortunetellers; she based all vital decisions on their predictions. She burned her astrology books after her brother showed her the passage in Deuteronomy that says consulting mediums is an abomination to God, and became an evangelical after she read in Jeremiah that God gives "a hope and a future."

About 10 percent of church members are without documentation, often well educated in their country of origin but struggling financially in France. Iranian political refugee Ali, 39, a maintenance worker at a Catholic school, "grew up dreaming of fighting against America." Azar, 35, his wife, comes from a family that provided bodyguard service to the Shah of Iran. Much like other Middle Eastern and North African immigrants I spoke with, both became Christians after Jesus appeared to them in dreams.

Ali Arhab is an Algerian émigré who converted from Islam and who now heads Channel North Africa, a TV station that broadcasts Christian programming by North Africans for French immigrants from North Africa in Algerian Arabic. There are no statistics available on the number of converts from Islam to Christianity in France, but he speculates the number may be close to 5,000, adding that "it's growing rapidly."

One reason for the uncertain number may be that some converts keep their Christianity a secret. A lot of them live in the "Communist-belt" suburbs around Paris and Lyon, which have become centers of radical Islam, says Siemon-Netto. "They attend prayer services on Fridays at the mosque and call themselves names like Mohammad. But on Sundays they attend services at churches where they are known as Jack or John." All this because "you have cases in France where Muslims obviously have been harmed or killed for apostasy."

A veteran missionary to French Muslims who I'll call Steve Adams, speaking on condition of anonymity, says he knows of about 17 support groups for Muslim converts to Christianity in France; all have formed in the last 10 years. "We're on the threshold of major breakthroughs with Muslims," Adams says. "God is saving religious leaders from Islam, like the two former Islamic terrorists I met." He and other sources say the revival going on in Kabylia in northern Algeria—the area that gave us Tertullian and Augustine—is likely to spill over into France.

"France is very resistant to ideas coming from outside the country," Adams says. "They're going to need something that makes them jealous, and they may be made jealous by the immigrants." But before this happens, evangelicals realize they have to work on their public image.

The Cult of Jimmy Carter

It's tricky to be a Christian in the country known for its sensuality. But the senses, too, can be the gate to the soul.

Marc Clementin used to be a partner in a powerful architectural firm, but he decided to quit and live off his paintings. Unlike most starving artists in Paris, he's done pretty well, selling more than 50 frames in the past two years.

"When you identify yourself as a Christian, some galleries don't want you around," he says. Same goes for women (this may be good, since some throw themselves at him quite literally). "You have to be very subtle. How do you promote Christ without being heavy and inspiring opposition, but being subtle, delicate, competent, interesting?" He attempted to do it in the series of paintings of the angst he felt following the crumbling of the World Trade Center towers. The despair seen in the faces of people falling contrasts with the surprising choice of bright colors, including gold. Borrowed from the stained glass in Notre Dame cathedral and Eastern Orthodox icons, the palette gives off hope.

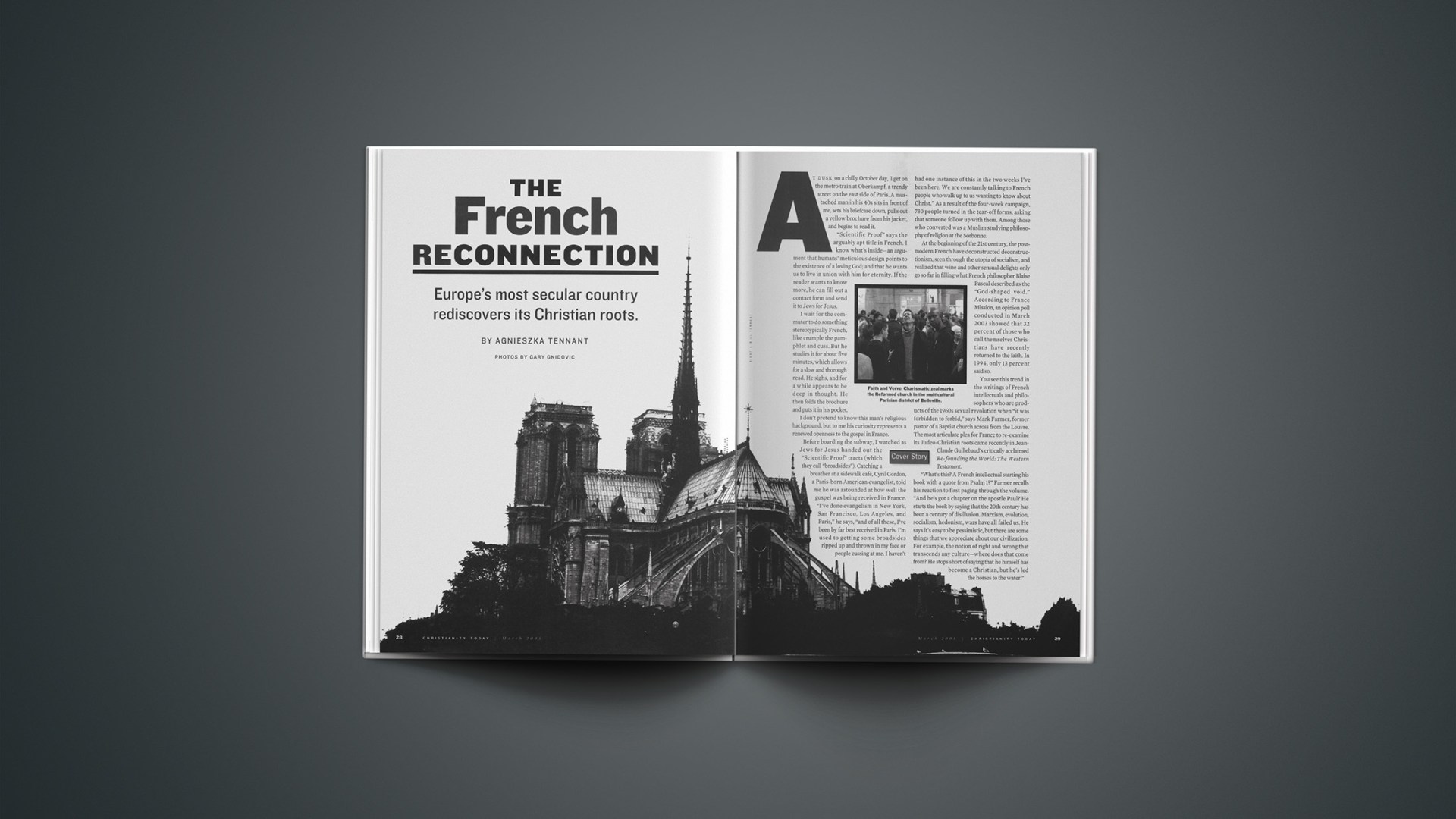

Clementin's mentor, Jim Beise, heads La Fonderie, a nonprofit ministry to between 80 and 100 artists. One time, before the group put on a four-day art fair at their charismatic Reformed church in the multiethnic district of Belleville in Paris, a belly dancer knocked on Beise's door. Not just any belly dancer. The professor of oriental dance came to Beise because "she felt that she needed permission to dance" during the fair. The permission granted, "Margarita danced discreetly, in costumes that were modest—in fact no belly was showing," Beise recalls. "About half of the 300 people who came to the dance were from the neighborhood where one-third are Arabs. We served oriental tea and pastries, and they felt transported back to their country. A clerk from the coffee shop near the church came to the dancer crying and saying, 'Thank you for honoring me.'"

This kind of presence evangelism is best suited for France, where evangelicals work to debunk the sense that anything that's not Catholic or mainline smells cultic.

Etienne Lhermenault, secretary general of the Federation of Evangelical Baptist Churches of France, remembers when as a 10-year-old boy he was at a record store, and overheard the sales clerks whispering about his Baptist father: "You know, he's in a cult. … The cult of Jimmy Carter!"

This image slowly started to fade when "in the 1980s Catholics realized that while their parishes declined, hundreds of evangelical churches were developing," says Fath. "The main French ecumenical review, L'Unité des Chrétiens, spearheaded by Catholics, published a special issue on evangelicals in 1984 that reflected a genuine desire to understand these new Christians."

"Our most recent problem is, of course, Bush," says Lhermenault, echoed by every other evangelical leader I met. With the re-election of George W. Bush and the war in Iraq, the mainstream French media—which make CBS and The New York Times sound like the current administration's puppets—began to pay unprecedented attention to evangelicals. For two months, journalists called Fath—widely known as a source on evangelicalism—almost daily.

But they still made mistakes. "The White House Taken Hostage by a Fundamentalist Cult" exclaimed a headline in the March 2003 issue of the popular Catholic-friendly weekly La Vie. "Evangelicals: The Cult That Wants to Conquer the World" read the error-laden cover published by the Nouvel Observateur in a March 2004 issue. But some see such publicity as growing pains.

"If evangelicals weren't well known, the media wouldn't have published articles about us," Brown says. "The Catholic Church gets criticized all the time. So I see it as part of the long-term progress. It enables us to correct perceptions." Indeed, after the Nouvel Observateur article came out, the editors of the magazine ended up apologizing to evangelical leaders in a private meeting. But their remorse did not result in a correction.

Fath attributes the media's unfairness to "a French tendency to counterbalance the threat of Islamic violence with a Christian equivalent," as if to imply that "U.S. Christian zealots might be as responsible as Islamic militants for the global violence we face."

Much more positive attention given to evangelicals is the "huge boom" of scholarly publications on evangelicals, Fath says. "Before the 1990s, Ph.D. [dissertations] on French evangelicals were extremely rare: an average of four in ten years. Now, there are a dozen in the making, and the tide seems to be growing year after year. Sociologists, anthropologists, historians, and political scientists all seem to realize that evangelicalism is a fascinating topic."

Things are changing at the state level, too. In January 2004, the former interior minister Nicolas Sarkozy praised evangelicals at a meeting of the French Evangelical Federation for their contributions to society. Last spring—at a time when a large number of Jewish cemeteries and synagogues were vandalized—Jacques Chirac publicly praised the Bible-believing community of Le Chambon for putting their lives at risk to save 5,000 Jews 60 years ago.

Evangelical churches are also learning to introduce themselves in savvy ways, for example by identifying themselves as Protestant. Pastor Chris Short says his Pontault-Combault congregation calls itself Eglise Protestante Baptiste (emphasis mine), "because Protestants aren't a cult." They get good press because "they're not Catholic and their pastors can marry." If in some places, Short says, evangelicals are perceived as a cult, then it's "mostly because of clumsy public relations."

His church is reaching out by sponsoring a coffee house, a market Bible stand, and Bible calendar distribution. "Visibility gives credibility," Short says. "As soon as you have a nice building, the attendance goes up." His congregation's new 300-seat sanctuary with a coffee club is a friendly place. Many people just walk in off the street to see what their church is all about. "We see new people weekly," Short says. And many of them are immigrants.

Welcome Wagon

The French government may not officially recognize religion, but it would do well to at least recognize evangelical communities' indirect, healing role in preventing one of France's greatest headaches: Islamic radicalism. Here's how it happens: As often the only institutions interested in befriending the poor, evangelical churches offer a safety net to immigrants. They help them assimilate—find apartments, jobs, friends. Consequently, evangelical churches seem to be stopping some of the newcomers from becoming easy prey for Muslim fundamentalists and from engaging in criminal behavior.

This hypothesis—first suggested to me by Baptist pastor Mark Farmer, who's observed it at work in his congregation—needs empirical support. But when I ran it by my other sources, they agreed with it, and often corroborated it anecdotally. Nogent's André Pownall heads a think tank that encourages French and West Indian church leaders to assimilate ethnic minorities. Some of the Muslims who live near the c&ma church in La Défense learned French through free lessons offered at the church. Tent-dwelling and marginalized Gypsies who convert and join the fast-growing Gypsy Pentecostal churches "stop living off robbery," says Eric Celelier, the founder of topchretien.com, an online meeting space for Christians visited by 2.7 million a year.

In France, the government takes care of the physical needs of immigrants and the poor, for example through its universal health care. But it cannot provide friendships, consolation, or hope. The followers of the gospel can—and do quite naturally.

The 350,000 evangelicals—along with an unknown number of evangelical-minded Catholics, Reformed, and Lutherans—may not be many among France's 60 million inhabitants. But a little yeast may just be enough to leaven the whole baguette.

Agnieszka Tennant is an associate editor of CT

Copyright © 2005 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

More articles on faith and secularism include:

That Other Church | Let's face it: Secularism is a religion. Let's treat it as such. (Dec. 21, 2004)

Misfires in the Tolerance Wars | Separating church and state now means separating belief and action. (Feb. 24, 2004)

One Nation Under Secularism | France's peculiar aversion to public religiosity is rooted in a sordid history of sectarian violence. (Feb. 13, 2004)

God's Funeral | What will keep faith from nearly disappearing in America? (By Philip Yancey, Sept. 03, 2002)

The Wages of Secularism | New laws won't prevent another Enron. (June 04, 2002)

Zarathustra Shrugged | What apologetics should look like in a skeptical age. (Sept. 5, 2001)

Other articles on France include:

'Cult' Report Legally Worthless | Courts cannot use the 1996 document in decisions. (Sept. 26, 2002)

Anti-Semitic Violence Spurs Crackdown | Attacks said to be prompted by violence in the Middle East. (May 07, 2002)

Eyewitness to a Massacre | The bloodbath that started on August 24, 1572, left thousands of corpses and dozens of disturbing questions. (Aug. 24, 2001)

From Books & Culture's issue on God is not dead:

The Real Story of Secularization | Is Europe a special case? (November/December 2002)

God Is Not Dead | The April 8, 1966, issue of Time magazine (scheduled to coincide with Easter) created a hubbub with the stark cover line, "Is God Dead?" (November/December 2002)

The Renaissance of Religion in Canada | They're not dropping out. They're dropping in. (November/December 2002)

American Gnostic | Harold Bloom's post-Christian nation ten years on (November/December 2002)

More articles on religious renewal include:

Amsterdam Amen | Amsterdam 2000 ends with a message from Billy Graham, a promise by 10,000 evangelists, and a unifying framework for worldwide evangelism. (Aug. 7, 2000)

Central Asia's Great Awakening | A decade-old ethnic church blooms despite government suspicion. (July 14, 2000)

Harvest Season? | Filipinos are turning to God, but rapid church growth strains relationships among Christians. (June 14, 1999)