Seventy-five-year-old Ken Crowell strolls along his massive, machinery-strewn assembly lines, chatting with blue-smocked, smiling workers who hail from Israel’s Tiberias region. More than 300 Arabs, Jews, and Christians work tidily together to produce antennas for wireless technology used by Motorola and Samsung. Some employees have been with Crowell’s company, Galtronics Inc., for more than 20 years. They find substantial incomes and benefits, subsidized all-you-can-eat buffet lunches, and often, salvation through Christ.

With more than one billion antennas sold and a 400-member church started by his company, Crowell has now opened plants in China (400 workers) and South Korea (40 engineers) that are “trying to duplicate” the Israel model. “They are managed by believers who know the vision of the company,” says Crowell. “The future is very good because everything is headed toward wireless.”

The company’s vision statement is displayed over its factory entrance: “COMMIT THY WAYS TO THE LORD, TRUST ALSO IN HIM, AND HE SHALL BRING IT TO PASS” (Psalm 37:5). By the 1990s, Galtronics had become the largest employer in northern Israel. Crowell describes his vision when he started the company in 1978: “The calling was first to go to an area where there was little or no Christian witness, to give employment to believers and nonbelievers in a safe working environment, and to support the building of a local church.”

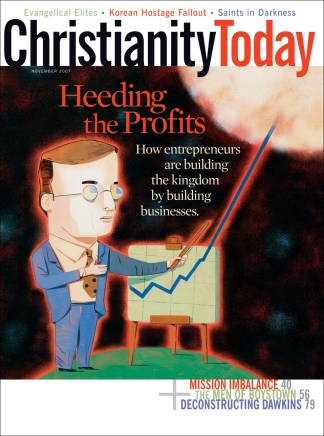

Today, gospel-oriented, free-market businesses like Galtronics are exploding worldwide as part of a growing movement to generate both temporal and eternal riches. When Crowell pioneered his work, he thought he was simply following God down a sometimes foggy but hopeful path of combining commerce with Christian witness. Now, some say Business as Mission (BAM) is the next great wave of evangelization.

More than Christian Capitalism

The phenomenon has many labels: “kingdom business,” “kingdom companies,” “for-profit missions,” “marketplace missions,” and “Great Commission companies,” to name a few. But observers agree the movement is already huge and growing quickly. BAM “is the big trend now, and everyone wants to say they’re doing it,” says Steve Rundle, associate professor of economics at Biola University. Rundle authored Great Commission Companies (2003) and has an upcoming book, An Overview of Business as Mission, written with fellow BAM scholar Neal Johnson.

BAM practitioners use business ventures not only to make a financial profit, but to act as an avenue for the gospel. They administer their companies like any Christian running a business: ethically, honestly, and with concern for the business’s neighbors. Yes, they exist to provide jobs and services and to make profits. But BAM companies are more than examples of Christian capitalism. The business itself is a means to spread the gospel and to plant churches. BAM companies increasingly have a global flavor, creating jobs in developing countries (unlike traditional aid or missions work) and making disciples who carry the gospel to the larger, hard-to-reach community.

The BAM model affirms that business is a Christian calling; that free-market profit is rooted in the cultural mandate; and that rightly done, “kingdom businesses” offer economic, social, and spiritual help to employees, customers, and nations. Big start-ups are often financed by wealthy Christians who expect financial rewards and ministry results. Small start-ups, called microenterprises, use small loans to achieve more modest ministry and profit goals. Some efforts, like Yeager Kenya Group, Inc., fall somewhere in between.

Last year, Bill Yeager of Montrose, Colorado, pumped $40,000 in personal savings from his successful software company into a radical idea. The son of former missionary parents in Kenya, Yeager began identifying and training more than 1,200 farmers north of Kenya’s Lake Victoria to grow USDA-certified organic onions for expanding healthfood markets in Europe and the United States. “It hit me that we could do business as a tool to improve lives in Africa,” says Yeager.

With another $70,000 from outside investors, Yeager is completing the expensive USDA training of his first group of farmers, who are members of a local cluster of 35 Kenyan churches. The rich, loamy jungle smells, scenic mountain waterfalls, and lovely lilt of the farmers’ Sabaot tribal language sometimes cloak their poverty. But the farmers’ incomes could now jump from $500 to $10,000 a year. “I’m just a typical 28-year-old kid,” says Yeager. Perhaps, but this entrepreneur is also addicted to a money-and-ministry vision. “It’s a risk, but I believe with all of my heart that this thing is going to take off.”

The number of BAM practitioners is hard to pinpoint, but the practitioners themselves may be too consumed with spreadsheets to worry about such statistics. “We’re not the big thinkers,” says Texas-based Johnny Combs, whose successful Paradigm Engineering frees him to assist BAM enterprises globally. “We’re doers,” he says.

Why Now?

BAMers take historic cues from Joseph in Egypt, the monastic tradition, Moravians, and William Carey—who all mixed businesses with ministry. In recent years, more than 2,000 books and 800 nonprofit organizations have encouraged combining commerce and faith in the workplace. They are piggybacking on a broader trend known as “social entrepreneurship,” which advocates using capitalism instead of charity to address social problems like poverty.

In the early 1980s, a group of executives formed Intent, an umbrella organization that had an early role in shaping the BAM movement. Members included Chicago southsider Clem Schultz, who in 1989 bought a controlling interest in AMI, an Asian technology manufacturer. Schultz, now 50, has felt called to Asian missions since he was 19. Today, AMI’s annual sales run from $30 to $50 million.

Intent is bullish on the prospects of business as missions. “The day of the Kingdom Professional in world missions has arrived,” Intent’s literature announces. “The remaining people who have yet to hear the gospel of Jesus Christ will be most appropriately accessed by Kingdom Professionals who intentionally use their God-given and market-honed skills as their legitimate passport to the nations.”

Today’s growing global economy helps make this vision possible. The ’90s “dot-com” bubble produced a massive overinvestment in infrastructure, says New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman in his bestseller, The World Is Flat. According to Friedman, this “resulted in the willy-nilly creation of a global undersea-underground fiber network, which in turn drove down the cost of transmitting voices, data, and images to practically zero.” Suddenly, “All kinds of work—from accounting to software writing—could be digitized, disaggregated, and shifted to any place in the world.” BAMers now tap new markets created by this global network in China, India, Russia, Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Central Asia.

BAMers target a niche, build a serious business plan, and act. They usually capitalize, not fundraise. They don’t always consult clergy members, who can make them feel like unspiritual “cash cows.” They don’t want to “serve God and mammon,” but they also know that money funds outreach (just ask the nonprofit groups who regularly seek their donations). “Christ was a carpenter for probably fifteen years and then an evangelist for about three years,” Combs quips. “So we businessmen had him for about five times longer.”

A Kingdom of Businesses

Many companies in the United States have for decades followed and encouraged Christian principles. Home maintenance provider ServiceMaster’s motto is, “Honor God in all we do.” The company explicitly emphasizes the spiritual.

Chick-fil-A founder S. Truett Cathy’s fast-food empire arose out of his sincere Baptist convictions. All Chick-fil-As are closed on Sundays, and in 1981, the company, with more than 1,200 free-standing restaurants and more than $1 billion in annual sales, adopted a corporate purpose statement that fleshes out Cathy’s longtime commitment: “To glorify God by being a faithful steward of all that he has entrusted to us. To have a positive influence on all who come in contact with Chick-fil-A.”

Usually, such American efforts have arisen from individual Christian entrepreneurs whose expanding employee base either explicitly or implicitly adopts their Christian ethic.

The same is true with BAM efforts. The movement is being pushed by Christian visionaries seeking a relational impact on employees and local communities. It is the global expression of the late-1980s evangelical movement that told Christians to take their faith to the workplace.

BAM workplaces have many faces, but three basic types seem most common.

Small companies begun from small loans: In the depths of Thailand, a group of 33 women run a jewelry-making business. More women are joining. The business’s name, “Nightlight,” may be a play on the seedy business each woman once ran. “All have left the sex industry,” reports entrepreneur and roving missionary Dallas Nash, an American wireless executive who helps such start-ups. Companies like Nightlight might be classified as “microenterprise development,” while other companies involve more extensive networks.

Big capital-based companies: Major corporations capitalize with big dollars to reach millions in a big-market, big-profit niche. Clem Schultz’s AMI started as a technology manufacturer and is now also a major Asian publisher of values-based books, running 10 operations in Asia and employing about 1,000 people. The holding company puts $1 to $10 million into each new effort, keeping 15 percent to 100 percent ownership. AMI’s large investments and good track record give it favor with local and national Asian governments. “We are given enormous benefits when we go to new areas,” says Schultz. The Christian non-nationals in AMI’s workforce total about 5 percent and represent 8 nations. “When people see people from South Africa, the United States, and England who all share this space and trust in Jesus,” Schultz says, “our faith appears much more robust.”

Outsourcing companies: Thomas Sudyk runs EC Group International, which employs physically disabled people in India, training them in information technology. “Widows, orphans, the blind, and the disabled are capable of productive work if they are given a chance,” asserts Sudyk on EC Group’s website. He started by finding a medical transcription niche, hiring a Christian manager in Chennai, India, capitalizing with $150,000, and securing one client, a U.S. medical company that would outsource work to Sudyk’s Indian staff. Today, he employs more than 60 people globally.

“Business done well changes lives, lifts societies, and glorifies God,” says Sudyk. “We expect our efforts to be seen as a blessing to the people of India and China by providing jobs, a decent workplace, and a fair wage,” and by putting “the needs of others as more important than our own.”

Mission’s Wild West

As BAM enterprises multiply, questions ferment: How explicit should ministry efforts be? What sort of spiritual care is a business equipped to offer? Is there a salary range for BAM executives, and can their salaries be too high? Who decides? What happens if a BAM effort goes awry into poor financial or religious practices? When a BAM has to lay people off, how does that affect their view of the gospel? To what extent does a Christian business in an oppressive society actually enable that regime? With no ground rules, Great Commission companies are proliferating outside any normative set of expectations, and without the spiritual accountability typically provided by denominations and churches.

“For people in the pews, business can be both a calling and a ministry,” Neal Johnson says. “But for people in the pulpits, business is often a mystery, and for some, even an anathema.”

Rundle acknowledges work needs to be done. “I am concerned. … Entrepreneurs have to be willing to be held accountable. They tend to be pretty strong-willed. I’ve heard it more than once: ‘Wait, I’m the one who put the money out there, and it is my business, and you can’t tell me what to do with my money and my business.'”

Accountability from a “sending church” or local church is sometimes happening, says Rundle, and other solutions may involve a council of stakeholders or an umbrella agency.

In Trujillo, Peru, a hybrid effort is underway, teaming the church with a for-profit business. Peru Mission began in the late 1990s, under the care of Christian Missionary Society based in Statesboro, Georgia. Much of Peru Mission’s funding comes from Presbyterian Church in America congregations. “We have a high view of the church as community,” explains Brad Ball, a businessman and early Mission member. “When you work in the context of the church as community, the church isn’t just a club you belong to, but it’s a place where people’s lives get intertwined and people are interdependent, and it’s territorial.”

Peru Mission has already planted two churches, one of 200 members and another of 50 members, both led by ordained Peruvian pastors. Medical missions are operating. The next step is to boost the local economy. Unlike the typical BAM, Peru Mission starts a church first, and then follows with businesses. Peru Mission is already making microloans of $50 to $100 in one village to finance street vendors in small convenience stores called bodegas.

Now, the company wants to make a bigger economic dent.

Four local carpenters make roof trusses under Peru Mission supervision. After a leave of absence, Ball is returning with an MBA from the University of Tennessee and a six-year plan to churn $950,000 in donations into building a 16-station carpentry and woodworking center. The business will use local, exotic hardwoods to make fine doors and furniture.

The effort is expected to make a profit of $74,000 by year four and net $1.1 million by year six. Though initial funds will come from donations, the for-profit shop will self-sustain and plow earnings back into the business, as well as into local schools, health centers, and community clinics.

Local churches will cooperate parish-wide with Peru Mission to give oversight to the woodworkers not only in trade, marketing, and business skills, but also in lifestyle issues with their families. “The facility itself is in the community,” says Ball. “These guys are part of the community. The economic part has to be in that context, as opposed to the more individualistic model of being a business leader. It will be a positive approach to accountability.”

Reconciling Through Work

In 1999, Randy Russ was president and CEO of Community Coffee, one of the largest family-owned coffee companies in America. Spurred by his Christian faith and by the discovery of a great-tasting specialty coffee in an area of Colombia wracked by civil war, Russ and his company began a relationship with 500 family farmers in the Toledo-Labateca region. They formed a cooperative of former rivals to ensure quality and delivery. Fair-trade prices have raised the standard of living, and an annual performance bonus is invested in social development projects. With support from key government and manufacturing groups, the farmers have built an agricultural high school, have invested in coffee processing equipment, and have improved their food supply with fish farming. Local parish priests see the efforts as healing for the community.

Today, Russ runs the Center for Marketplace Ministry and teaches marketing at Belhaven College in Jackson, Mississippi. He nurtures students’ vision for BAM. “Ultimately the hope is that thousands more businesspeople will be affirmed to use their talents and business skills in sharing the Good News through the marketplace,” states Russ. “It is a meaningful part of our reconciliation with God and each other when we surrender our talents and businesses to him.”

Ken Crowell and Bill Yeager both understand. In addition to branching out from Tiberias to China and South Korea, Crowell has spun off five more companies in the Galilee region under a parent company, Gal Group Christian Industries.

Meanwhile, Bill Yeager’s organic farmers in Kenya face the challenges of overseas shipping, opening new markets, and ongoing certification. Yeager sees potential, however, to expand from onion production to sweet potato, pineapple, and green chili markets, among others. But it is the relationships with the local farmers and their children that drive him the most. “Having met the farmers and broken bread with them, there is just no way I am going to quit”—even if the effort isn’t “designed to make me rich,” he says.

BAM isn’t for people looking solely for profits, says Crowell. But if you want to generate eternal returns in a company where you can pick up a Bible in the office or feel comfortable evangelizing in a transparent environment that traditional missions might never reach, what are you waiting for?

Joe Maxwell is a former Christianity Today news editor, and now a journalist-in-residence at Belhaven College in Jackson, Mississippi.

Copyright © 2007 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Business as Mission Network has links to other organizations, books, conferences, most admired companies, and more.

Previous Christianity Today articles on business include:

From Hand Out to Hand Up | Three Arkansas entrepreneurs are helping build Rwanda’s largest bank for the poorest of the poor. (November 1, 2007)

The Good Shepherds | A small but vigorous movement believes that in farming is the preservation of the world. (October 25, 2007)

Surviving the Mortgage Crisis | Most Christian lenders remain strong during sub-prime debacle. (October 12, 2007)

Crop of Concerns | Farm bill draws out Christian reformers worried about subsidies. (August 10, 2007)

Defining Business Success | A CEO on why core values are not enough. (February 5, 2007)

Dollars and Sense | How Salem Communications makes its money. (January 26, 2007)