Jamaal Simmons went to Zambia to wash the feet of AIDS orphans. For nearly a month he slept in tents and bathed out of buckets. It was a humbling experience for the 19-year-old, but the hardships of Zambia were nothing compared to boot camp.

Welcome to Teen Missions International, which offers summer missionary training camps or “boot camps” as rigorous as the name implies. Here there are no s’mores by a cozy campfire. Instead, the camps aim to recreate third-world conditions for young missionaries-in-training, and every year some 700 young people gladly turn out. The teens give up such luxuries as electricity and running water before heading out into the world together to nurture orphans, build granaries, dig wells, and minister in such far-flung places as Tanzania, Mongolia, Indonesia, Belize, and Ukraine.

“Boot camp for me was the culture shock,” said Simmons, of Salisbury, Maryland. His trip last summer to Zambia was his first trip out of the United States.

Here campers are stripped of virtually every teenage trapping. There are no cell phones, iPods, or laptops. No candy or soda. Not even electricity or running water. The culture here is entrenched in discipline. Campers sleep in tents and use buckets to bathe, launder clothing, and flush toilets. They bear the Floridian summer heat in long pants and hiking shoes to protect against snakes and bugs. Many wear pajama pants all day, since cotton pants breathe easier and dry quicker than jeans in the stifling heat. The air is thick with mosquitoes, heavy with humidity, and pungent from the smell of sweaty teenagers.

Yet from this stripped-down existence springs an innocent and unbridled passion for one of Christianity’s most basic tenets: Jesus’ directive that his followers make disciples of all nations. It is a passion untarnished by politics, international tensions, and the cynicism that can come with age. Here the kids are hot, dirty, tired, and happy. They are having fun. They are excited about evangelism, excited to take their religious beliefs with them into the world. It is a youthful exuberance, the kind that nudges a 19-year-old to take his first mission trip and his first trip out of the U.S. into one of the most difficult countries in Africa. And why not? What could go wrong?

“I’m not really nervous about it. It hit me that it’s getting closer and closer. … I have no idea what to expect,” Simmons said a day before leaving the camp for Africa with his group of about two dozen campers. “I feel God calling me to go. If that’s what he wants me to do, then that’s what I want to do. It’s not about me.”

Water Bottle Luxury

Speak clearly and don’t chew gum. Rather than listen to you, your audience will watch you chew gum. Be wary of pride. Remember, it’s God who saves souls.

At Teen Missions, campers give up virtually their entire summer for evangelism. They spend two weeks in Merritt Island, Florida, learning the work of a missionary before heading into the world in teams of about 25. They are schooled in evangelism, construction, and Bible studies. They don purple construction hats as they work the ground with hoes and wheelbarrows. They practice public speaking and learn to share their faith in ways that transcend linguistic and cultural barriers, such as through puppet shows. After their mission trip, they return to Merritt Island for a few more days to reflect on their experiences before heading home at summer’s end.

Teen Missions runs a bare-bones operation on a $3 million annual budget sustained entirely by donors. During the busy summer, some offices are outside, sheltered from the sun by a canopy. Staffers raise their own salaries through donors. Campers also raise their own camp and travel fees, plus enough for another child (from $2,500 to $4,000) that funds 34 international boot camps where, for instance, an African child can train to be a missionary in his or her own country. “Peanut” and “mustard seed” camps also are available to train children ages 4 to 9 for domestic missions. Teen Missions sends adults on trips, too.

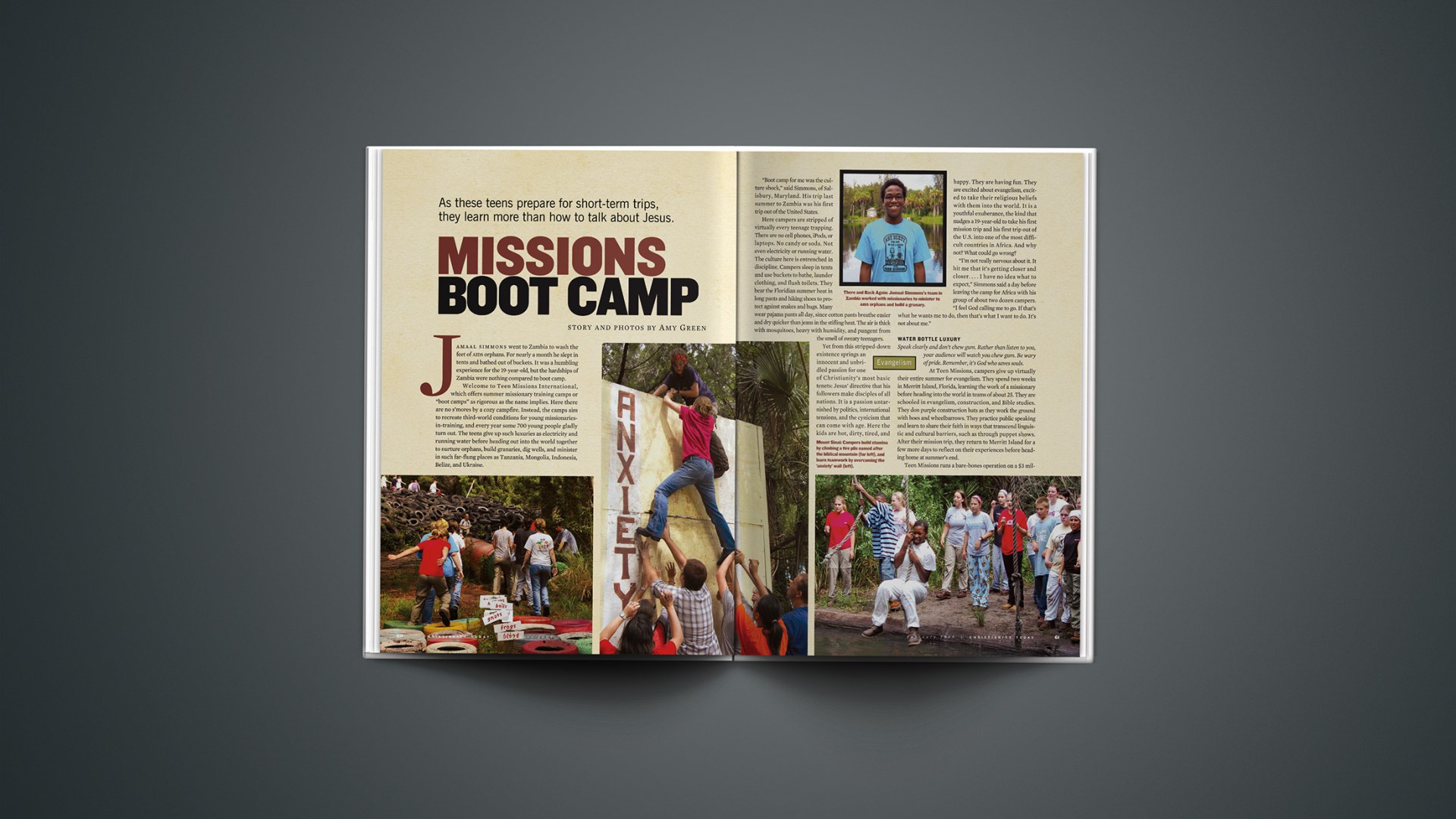

On an average day at a Teen Missions camp, attendees rise before dawn. For Simmons’s team, the day begins with what’s either lovingly or loathingly nicknamed “the OC,” an obstacle course meant to build teamwork and mental and physical stamina. At running speed, the campers complete obstacles inspired by biblical stories. There is Mount Sinai, a pile of tires, and Jacob’s Ladder, a rope ladder. They swing over a retention pond, wiggle through small plastic tubes, and climb wooden walls painted with words like “anxiety.” Standing at least 10 feet high, the walls require an entire team working together to overcome.

At meals, campers must eat everything on their plates as training for the hospitality they’ll receive in third-world countries, where some meals are prepared with the labors of entire villages in which many are starving. In their free time, campers rest and write friends and family back home. Some remove their shoes to give their feet air. One camper on Simmons’s team suffers from jungle rot. Her skin is peeling from her feet. Campers quickly realize what they used to take for granted. Air conditioning is a big one here.

Simmons points to a water bottle, an old Dasani one I filled up before heading to the camp.

“That is a luxury,” he said, eyeing it with longing.

A plumber-turned-pastor, Bob Bland began organizing Teen Missions in 1970. He got the idea from a 14-year-old who told him at a religious conference that she wanted to be a missionary but complained that everyone told her she was too young.

“I want to do something for the Lord now,” she told him.

In an early year of developing Teen Missions, Bland took a group of teens to Peru, and it went badly—one teen was bit by a poisonous snake and two others nearly drowned in a river. Bland believed the teens needed training and discipline, so he set up a missionary training camp in Greenfield, Ohio, at a campground operated by the Christian Union, a small evangelical denomination active primarily in the Midwest in which Bland is ordained. He and his wife began looking for property in Miami because of its proximity to Latin America, but in 1975 settled on 265 acres of much more affordable swampland in Merritt Island, near Kennedy Space Center on Florida’s east coast.

Teen Missions has trained some 40,000 young missionaries, some of whom have gone on to become career missionaries. The rigorous training and discipline are for their benefit, Bland said. Campers are taught to follow rules no matter what, because when they are abroad, a simple misunderstanding due to cultural differences could endanger not only their mission work, but the lives of themselves and those around them.

“We tell kids this is a missionary training camp. This isn’t pamper camp. That’s down the road,” he said dryly. “We can’t teach all those [cultural] differences here, but we can teach discipline. You may not understand, but there is a reason.”

Rite of Passage

Not long ago, young missionaries like Simmons didn’t exist, and short-term missions were rare. In a phenomenon that many have noted, today young missionaries are everywhere. Short-term mission trips are a summer tradition for many North American congregations and a rite of passage for many young evangelicals. Organizations like Youth With a Mission (YWAM), Café 1040, and Young Life are deploying young missionaries by the thousands. Of the 16,000 Southern Baptist volunteers who since early 2006 have helped in the restoration of New Orleans, some 75 percent have been high school and college students affiliated with youth groups and college ministries, estimates Jim Burton, a senior director of the North American Mission Board, the Southern Baptist domestic missions agency.

Ever since the hippies of the ’60s demonstrated a carefree willingness to “run off into the world on shoestring budgets,” organizations have been responding to a quickly growing interest in short-term missions among young people, says Paul Filidis, director of international communications for YWAM. The organization has 1,000 locations and some 20,000 young missionaries in training or at work worldwide, he said.

Usually on these short trips it’s the missionaries who are most influenced, says Jennifer Smith, a student mobilizer for Café 1040, which sends college students into the “10/40 window” from its base in Alpharetta, Georgia. The organization wants to expose young people to missions work in hopes that some of them will continue it throughout their lives, she said.

Teen Missions is unique in the short-term mission world, however, because it was among the first to start a boot camp. Today it is among the most rigorous missionary training programs of its kind in the country.

These kinds of high-intensity experiences, whether in missions or youth group summer camp activities, have the potential to powerfully shape teens, says Christian Smith, professor of sociology at the University of Notre Dame. “The high-intensity-ness can be used for good or bad. It depends on how the high intensity is directed.”

Youth camps like Teen Missions “try to help students stretch beyond their comfort zones,” says Terry Linhart, dean of the School of Religion and Philosophy at Bethel College in Mishawaka, Indiana. If the experience leads teens to become more active adult Christians, that’s a good thing, he says.

“It’s difficult to see an immediate change in behavior. They don’t necessarily give more to missions,” says Linhart, whose Ph.D. studies focused on short-term missions. However, “It’s producing change down the road. It’s like we’re planting a seed when students, particularly youth, see the world differently. … They get perspective on the world that’s fresh and transformational.”

Dependent on God

First they checked for sores and cleaned them with peroxide. Then they washed the orphans’ feet with soap and water. Finally they applied lotion and gave every orphan a pair of shoes. For many orphans, the shoes were the first pair they had ever owned.

Simmons is a big guy. He is at least six feet tall and has big bones, big hair, and a big smile. Sometimes he punctuates his sentences with a self-conscious laugh. But he is sober as he describes his team’s experience in Africa. He was struck by the poverty, the children with ragged clothes and swollen bellies who endured the chilly nights with little more than thin blankets. One child wore an old SpongeBob SquarePants T-shirt. Simmons describes the quiet reverence they had for what his team was doing. One child knelt before Simmons after he washed his feet.

“I did not feel I deserved to be knelt to,” he said, his head bowed as he talked. The team visited a few different villages, some comprised entirely of huts and others that were more urban with brick homes and stores. Simmons’s team helped in the construction of a granary. They ministered to small audiences and persuaded some—children and adults—to become Christians. They learned African songs, and Simmons, a student at Wor-Wic Community College in Salisbury, Maryland, took his guitar and wrote a song about his experience with his friend Kirk Kroeger, 17, of Fredericksburg, Texas. The children liked having their pictures taken with digital cameras and seeing the photos. Simmons played duck-duck-goose with the children and came to feel like a brother to them. He had something in common with them: He was adopted as a baby.

As teenagers are often accused of being self-involved, it was perhaps unsurprising that what Simmons and most of his teammates brought back with them from Zambia was a desire to put others before themselves more diligently. Niki McDanel, 13, of Casselberry, Florida, described how three orphans shared a single blanket at night to keep warm and another orphan with a mental disability had little care available to him. She decided she wanted to become a famous actress and, like Angelina Jolie, spread awareness about Africa.

“People don’t know the half of it,” said McDanel, with long dark hair and purple, wire-rimmed glasses. “Once you meet these kids, you realize it’s not just aids that’s the problem. They die of things like malaria and things it would only take $5 to cure.”

Simmons missed his own bed while in Africa. He missed the luxuries he had back home. But over time he came to realize those things were “distractions,” as he put it, drawing his attention away from the children he was sent to Africa to care for. The trip reordered his priorities, he said—God first, then others, and then himself. Once he let go of those distractions, he said, he could enjoy himself and his time with the children.

Was boot camp worth it? Oh yes, he said. Simmons arrived in Zambia well prepared for the worst of living conditions. “The Christians in Africa were different [from] American Christians. There, all you have to depend on is God so they’re totally focused on God,” he said. “While we were out there God really showed me myself. … It was a challenge, really seeing myself.”

Amy Green is a journalist in Orlando.

Copyright © 2008 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Teen Missions International’s website has more about its programs.

Recent articles on youth ministries include “Gospel Talk,” about the shakeup in North Carolina Young Life staff, and “Young, Restless, and Ready for Revival.”