Ignace Maloba, a Wesleyan pastor in rural Congo, has had an unexpected new ministry as of late: hunting child witches. Four years ago, local informants led him to the dusty back streets of Kolwezi, a copper-mining town 160 miles from Lubumbashi, a major city in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC, formerly Zaire).

After traversing the area several times, Maloba finally found the “witches”—two girls and four boys incarcerated in a forlorn church compound. “I was extremely surprised,” the pastor told Christianity Today.

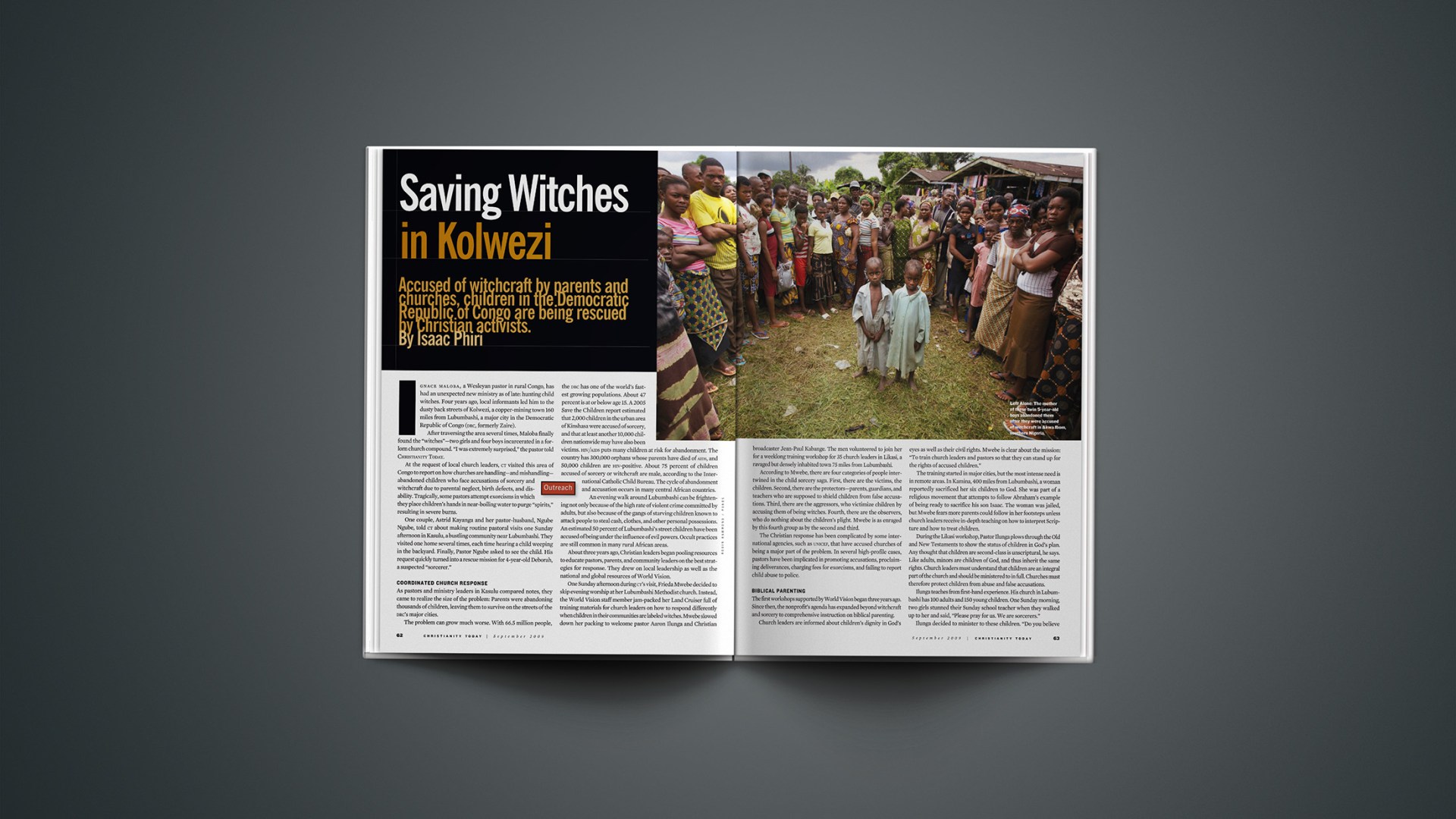

At the request of local church leaders, CT visited this area of Congo to report on how churches are handling—and mishandling—abandoned children who face accusations of sorcery and witchcraft due to parental neglect, birth defects, and disability. Tragically, some pastors attempt exorcisms in which they place children’s hands in near-boiling water to purge “spirits,” resulting in severe burns.

One couple, Astrid Kayanga and her pastor-husband, Ngube Ngube, told CT about making routine pastoral visits one Sunday afternoon in Kasulu, a bustling community near Lubumbashi. They visited one home several times, each time hearing a child weeping in the backyard. Finally, Pastor Ngube asked to see the child. His request quickly turned into a rescue mission for 4-year-old Deborah, a suspected “sorcerer.”

Coordinated Church Response

As pastors and ministry leaders in Kasulu compared notes, they came to realize the size of the problem: Parents were abandoning thousands of children, leaving them to survive on the streets of the DRC’s major cities.

The problem can grow much worse. With 66.5 million people, the DRC has one of the world’s fastest growing populations. About 47 percent is at or below age 15. A 2005 Save the Children report estimated that 2,000 children in the urban area of Kinshasa were accused of sorcery, and that at least another 10,000 children nationwide may have also been victims. HIV/AIDS puts many children at risk for abandonment. The country has 300,000 orphans whose parents have died of AIDS, and 50,000 children are HIV-positive. About 75 percent of children accused of sorcery or witchcraft are male, according to the International Catholic Child Bureau. The cycle of abandonment and accusation occurs in many central African countries.

An evening walk around Lubumbashi can be frightening not only because of the high rate of violent crime committed by adults, but also because of the gangs of starving children known to attack people to steal cash, clothes, and other personal possessions. An estimated 50 percent of Lubumbashi’s street children have been accused of being under the influence of evil powers. Occult practices are still common in many rural African areas.

About three years ago, Christian leaders began pooling resources to educate pastors, parents, and community leaders on the best strategies for response. They drew on local leadership as well as the national and global resources of World Vision.

One Sunday afternoon during CT’s visit, Frieda Mwebe decided to skip evening worship at her Lubumbashi Methodist church. Instead, the World Vision staff member jam-packed her Land Cruiser full of training materials for church leaders on how to respond differently when children in their communities are labeled witches. Mwebe slowed down her packing to welcome pastor Aaron Ilunga and Christian broadcaster Jean-Paul Kabange. The men volunteered to join her for a weeklong training workshop for 35 church leaders in Likasi, a ravaged but densely inhabited town 75 miles from Lubumbashi.

According to Mwebe, there are four categories of people intertwined in the child sorcery saga. First, there are the victims, the children. Second, there are the protectors—parents, guardians, and teachers who are supposed to shield children from false accusations. Third, there are the aggressors, who victimize children by accusing them of being witches. Fourth, there are the observers, who do nothing about the children’s plight. Mwebe is as enraged by this fourth group as by the second and third.

The Christian response has been complicated by some international agencies, such as UNICEF, that have accused churches of being a major part of the problem. In several high-profile cases, pastors have been implicated in promoting accusations, proclaiming deliverances, charging fees for exorcisms, and failing to report child abuse to police.

Biblical Parenting

The first workshops supported by World Vision began three years ago. Since then, the nonprofit’s agenda has expanded beyond witchcraft and sorcery to comprehensive instruction on biblical parenting.

Church leaders are informed about children’s dignity in God’s eyes as well as their civil rights. Mwebe is clear about the mission: “To train church leaders and pastors so that they can stand up for the rights of accused children.”

The training started in major cities, but the most intense need is in remote areas. In Kamina, 400 miles from Lubumbashi, a woman reportedly sacrificed her six children to God. She was part of a religious movement that attempts to follow Abraham’s example of being ready to sacrifice his son Isaac. The woman was jailed, but Mwebe fears more parents could follow in her footsteps unless church leaders receive in-depth teaching on how to interpret Scripture and how to treat children.

During the Likasi workshop, Pastor Ilunga plows through the Old and New Testaments to show the status of children in God’s plan. Any thought that children are second-class is unscriptural, he says. Like adults, minors are children of God, and thus inherit the same rights. Church leaders must understand that children are an integral part of the church and should be ministered to in full. Churches must therefore protect children from abuse and false accusations.

Ilunga teaches from first-hand experience. His church in Lubumbashi has 100 adults and 150 young children. One Sunday morning, two girls stunned their Sunday school teacher when they walked up to her and said, “Please pray for us. We are sorcerers.”

Ilunga decided to minister to these children. “Do you believe that Jesus is powerful enough to break the power of Satan?” That was all he asked the 12-year-olds. Once they said yes, he prayed for them and sent them home. The Sunday school teacher later visited the girls’ homes, and their parents started attending church.

But not all such episodes are easy successes. Another child at Pastor Ilunga’s church went home excited after receiving prayer. She told her grandmother. But the grandmother had initiated the girl into witchcraft. Eventually, Ilunga took the girl into his home, later reconciling her with another relative.

Many church leaders are unaware of how widespread witchcraft accusations are. In August 2006, Pastor Maloba was invited to a workshop in Kolwezi. He listened doubtfully as Mwebe of World Vision pleaded with church leaders to consider the protection of children an integral part of their ministry. “To protect children is an obligation, not an option,” she argued.

Maloba remained unconvinced. “I decided to go into the field and see for myself if this was true,” he told CT at the Likasi meeting, where he was now presenting. It did not take much effort: His own neighbors told him of cases of children being driven away from their homes or handed over to “prophets” to receive exorcism.

“This made me see that the problem existed near my home,” Maloba said. The discovery drove him to action, and he began locating children held in church compounds in which they were being “delivered” from evil spirits.

“Which one is the witch here?” he would ask the harassed minors.

He would then negotiate their release to their families or to a facility for vulnerable children. He joined a network of 65 congregations in Kolwezi working together to help such children. He also began using his weekly broadcast on a local Christian radio station to discuss the problem. Due to Maloba’s efforts, 33 children have been reintegrated into their families, and in total, newly trained leaders have intervened to resolve abandonment and false charges against more than 800 children in the region.

Pastors have also agreed to abide by a new code of conduct when a child is accused of sorcery. The first rule: Don’t do anything Jesus wouldn’t do, including any form of torture.

Complex Causes

Lack of awareness extends beyond the church. Many government officials are just as ignorant. In Likasi, local officials responsible for children and youth confidently told CT that there were no cases of child sorcery in their town.

One day later, CT came across credible reports that an abandoned child was about to be attacked by a local mob after being labeled as under the influence of evil spirits.

University of Lubumbashi psychologist Mukendi Nkongolo told CT that a variety of reasons lie behind the charges. Among the chronic poor, parents may use witchcraft as an excuse to abandon their children to reduce the family’s financial burden.

The displacement of people by economic or political crises leads to densely crowded living in towns and cities. Cut off from their extended families, children find it hard to disprove accusations and thus suffer the most.

Professor Nkongolo says some religious leaders make things worse, citing as an example a church leader in Lubumbashi who diagnosed four children as “full of bad spirits.” The treatment: “He took a burning piece of wood and put it on their bodies.”

Such abuse is a serious crime. Lubumbashi judge Arthur Ndalama does not mince words about such cases. “The law requires us to work with evidence,” he told CT. “We consider the children victims.” Penalties that Ndalama can impose range from one month to one year in jail for child abuse. He sends more serious cases to higher courts, which can impose harsher sentences.

Asked about the case of the pastor claiming to exorcise children by burning them, Ndalama quickly responded, “He is in jail right now.” But he does not rejoice in sending religious leaders to jail. “It is really hard because people put so much trust in pastors.”

Church leaders committed to orthodox ministry are deeply troubled by these events. CT sat down with four pastors in the second-floor lounge of Channel of Life, an FM radio station that broadcasts to Lubumbashi’s 1.3 million citizens.

One of the pastors, Alexander Nkongolo of Kolwezi-based Salvation of the Christian Union, is infuriated by bogus preachers who, claiming the power to deliver, end up burning, beating, and abusing children.

“I do not like this kind of thing. They are not doing deliverance,” he emphasized. “If they were doing true deliverance, I would be happy.”

Lubumbashi pastor Mwamba Mushikonke added that churches where these abuses occur are steeped in mysticism and chase after miracles. According to Mushikonke, adults are promised blessings, but when the blessings do not come, a child—usually an orphan in the community—is picked on and said to be the hindrance to a spiritual breakthrough.

“This is because the children are defenseless,” Mushikonke said.

Kasanda Mandolo, another Lubumbashi pastor, agreed.

“The pastors claim to be engaged in spiritual warfare, but are simply after money,” he said. When pastors’ spiritual weapons appear to not work, they have to find a reason to explain the failure of their claims. “They promise someone that he will find a job after prayers, but if the person fails to find a job because of economic conditions in the country, they accuse a child of bringing bad luck.”

Mandolo believes the government must do something to bring these wayward churches and preachers under control. “You will find 20 churches on every street,” he observed. “Why let everyone do what they want?”

Mandolo wants to make it clear that he is not calling for the state to manage churches but to institute at least some oversight. “Let the government issue licenses to legitimate ministers,” he suggested.

In the end, the four pastors agreed that the core problem is inadequate training and lack of discipline. “Where pastors are properly trained, there are no such practices,” said Ilunga, also a teacher at a Lubumbashi Bible college. Most preachers who abuse children are poorly trained and resist the authority of legitimate church structures. “When they are excommunicated, they decide to start their own church,” said Ilunga.

Mwebe glows as she listens to the pastors debate the child sorcery issue with so much conviction. So does Channel of Life station manager and broadcaster Kabange, who has been at the forefront of using radio to raise awareness among adults and children. After the group interview, Kabange chats with some of the pastors about featuring them on future broadcasts about child sorcery.

Left to Die

At the time of their intervention, Astrid and husband Ngube took one look at the frail, 4-year-old Deborah and were horrified. Forsaking traditional courtesies, Ngube demanded, “Can I take this child?”

“Yes, you can,” came the soulless response.

They rushed home to bathe Deborah and give her food and medicine. The next morning, a doctor tested her for HIV. The test came back negative. For the most part, Deborah was suffering from malnourishment.

They later discovered that Deborah was an orphan. Relatives had taken her in but had soon concluded that she was evil. They had dumped her in the hot, garbage-strewn backyard without food, water, or any care. She was left to die. Today, Astrid eagerly shows off photos of Deborah, now 6, playing.

In Kolwezi, Pastor Maloba hones his ability to discover children falsely accused of witchcraft and sorcery. He believes that if more churches get involved, fewer and fewer children will be incarcerated in desolate church compounds.

“God, we know you are powerful”—this is his prayer nowadays. Deborah, along with the thousands of other child “sorcerers” rescued by church action, would agree.

Isaac Phiri is a journalist based in Lusaka, Zambia.

Copyright © 2009 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Christianity Today also posted “Who’s Afraid of Witches” today.

CT has a special section about the Democratic Republic of Congo on our site, including:

Miracle Vote | Churches in the Democratic Republic of the Congo rejoice over first free elections in 46 years. (January 17, 2007)

Hope in the Heart of Darkness | With 3.9 million dead and 40,000 raped, Christians work for renewal and healing in Congo’s killing fields. (July 1, 2006)

Born Again and Again | ‘Jesus gives us strength,’ says a Congolese pastor. (July 1, 2006)

Previous articles by Isaac Phiri include:

Hunger Isn’t History | The world produces more food than ever. So why do nearly a billion people still not have enough to eat? (November 7, 2008)

Gospel Riches | Africa’s rapid embrace of prosperity Pentecostalism provokes concern–and hope. (July 6, 2007)

Abstinence Brings ‘Dignity’ | Traveling in Africa, First Lady Laura Bush speaks in favor of faith-based HIV prevention. (June 29, 2007)