When the Amish community of Nickel Mines, Pennsylvania extended their forgiveness to the widow and family of the man who just hours earlier had shot and killed five of their own young daughters in October 2006, the world marveled in disbelief. Where was the anger, the bitterness, or the doubt that plague most people who experience such senseless tragedy? As the hours stretched into days and days piled into weeks, people struggled to wrap their minds around what made these people so different—beyond the bonnets and buggies, there was an unfamiliar certainty that guided them through the pain. Their willingness to forgive stemmed from a firm conviction in God’s sovereignty over all things, both good and tragically, incomprehensibly bad.

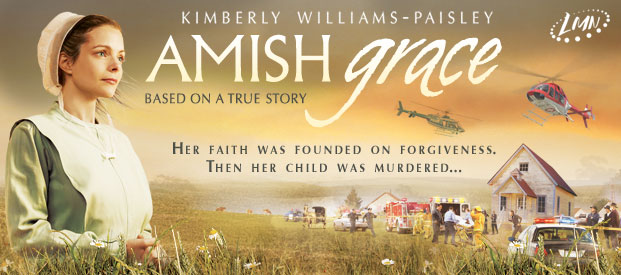

Amish Grace, a made-for-TV movie airing on the Lifetime Movie Network this Sunday, March 28, at 8/7c, loses some of the story’s power by focusing on the fictional Ida Graber (Kimberly Williams-Paisley), an Amish wife and mother who struggles to accept her daughter’s death and balks at the idea of forgiving the family of a man who caused her so much pain. She is supposed to be relatable, but that is the opposite of what made this story so powerful in the first place. She looks and sounds like any other suburban mom in a similar situation. She questions God and lashes out at her friends who so easily accept their religion’s answers. But it is the lack of this kind of response that made the story so compelling in the first place.

The movie is based on the book Amish Grace: How Forgiveness Redeemed a Tragedy by Donald Kraybill, Steven Nolt, and David Weaver-Zercher, but the authors have distanced themselves from the project “out of respect to our friends in the Amish community and especially those related to the Nickel Mines tragedy,” according to a joint statement. The Amish shy from media attention and do not allow themselves to be photographed or identified in the press. Some from within the community anonymously expressed discomfort with the project: “We’re not happy. It’s not something we want to be a part of. We were too close to it,” says one Amish woman.

About a month after the shooting, a friend arranged for me and others to join a group of “Englishers” (the Amish word for non-Amish people) for dinner with an Amish family just outside of Nickel Mines. We spent most of the evening discussing the events of the past few weeks—the media attention, the public fascination with their way of life, and, most of all, their response to it. They told us stories of children who had dreams of their friends playing in heaven—they had never been exposed to violent images that might now fill their minds. They expressed their sorrow for the families affected, including the shooter’s wife and children. They expressed thankfulness for the strong community that could offer comfort and support in such difficult times. But they never expressed anything less that complete solidarity and faith in God’s sovereignty over it all. This is what makes their story of grace and forgiveness so powerful—it is not earned. It is not something they resigned themselves to when everything else had failed.

The power of this story is still too strong to get lost in the film. Anyone who watches it will feel its impact, particularly through the character of Amy Roberts (Tammy Blanchard), the killer’s widow who is overwhelmed by the grace of the Amish community. Through her grief and struggle to accept the forgiveness extended to her and her family in their darkest hour, we see the power of a community whose faith points back to a God who first forgives us.

Do you plan to watch the movie? If you’ve seen it, what did you think of its portrayal of faith and forgiveness?

Click here for more of CT’s coverage on the Amish and the Nickel Mines shooting.