In the Iowa caucuses of 1976, The New York Times reported on the surprising impact of a new force in American politics. This force propelled a relative unknown to victory in Iowa and eventually earned him the nomination of his party. The candidate was Jimmy Carter, the party Democratic, and the new political force evangelicals.

Moral Minority: The Evangelical Left in an Age of Conservatism (Politics and Culture in Modern America)

University of Pennsylvania Press

384 pages

$25.00

Carter's shocking victory in Iowa would propel him to the Democratic nomination, and in the general election Carter would benefit from the active support of Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, and Jimmy Allen, the president of the Southern Baptist Convention, in his defeat of Republican Gerald Ford. Four years later evangelicals would prove to be a key plank in a Religious Right's effort to defeat Carter and elevate Ronald Reagan to the presidency. A new book tells the dramatic story of the grassroots movements of the evangelical left that formed in the '60s and '70s and helped pave the way for Carter's stunning victory, and explains the forces that would leave those movements in ideological retreat in the '80s and '90s. It's a complicated story told with great skill and clarity by David R. Swartz in Moral Minority: The Evangelical Left in an Age of Conservatism (University of Pennsylvania Press).

Swartz, assistant professor of history at Asbury University, did his studies at Notre Dame under the tutelage of first George Marsden and then Mark Noll, and his writing reflects the decades of careful evangelical scholarship that those two have pioneered. Swartz has produced a must read not only for those interested in American religion and politics, but also for students of global Christianity. In relatively short order (the book's main text comes in at 266 pages), Swartz gives a richly textured narrative of some of evangelicalism's brightest thinkers, most creative activists, and most controversial provocateurs.

In these pages legendary, now-deceased figures like Carl F. H. Henry, Mark Hatfield, and Francis Schaeffer come alive again in fresh perspective and telling anecdotes. Other individuals who are still with us—like John Perkins, Jim Wallis, and Samuel Escobar—are helpfully placed in the broader context of global events and evangelical controversies. And major evangelical institutions like InterVarsity, Calvin College, and Fuller Theological Seminary are woven into the story with a care and sensitivity sure to educate even their most dedicated supporters. The end result is a book that is both a pleasure to read and a conversation to join, regardless of the political or religious convictions of the reader.

Rise to Prominence

Swartz tells the story of what he terms the "Evangelical Left" in three parts, looking first at its emergence, then at its broadening, and finally at its seeming retreat. In the first two parts Swartz uses a very effective technique of centering each chapter on a particular individual and social issue. There are, for instance, chapters on "Jim Wallis and Vietnam," "Richard Mouw and the Reforming of Evangelical Politics," and "Ron Sider and the Politics of Simple Living." These chapters make for engaging reading, as Swartz weaves biographical details, institutional histories, and broader secular trends into explanations of important developments in evangelical social thought. It is clear that Swartz is sympathetic to the characters but not uncritical of the choices they make and the directions in which their movements proceed.

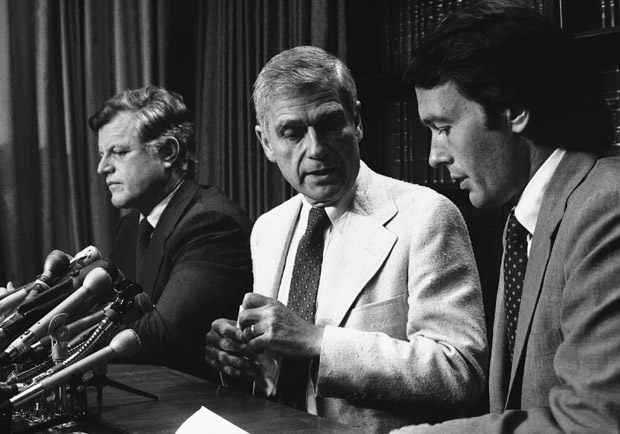

Swartz argues persuasively that the most significant politician to arise out of the Evangelical Left was Mark Hatfield, a moderate Republican from Oregon. Swartz shows how Hatfield's strong opposition to the Vietnam War had its roots in his experience as a lieutenant serving in the Pacific during World War II. Due to his military position, Hatfield was "among the first Americans to see the devastation of the nuclear strike on Hiroshima." As Hatfield rose to power in the Oregon Republican Party, eventually serving in different elected capacities for 45 years, he never lost touch with the formative experience of war in Asia.

"Here were people [in Hiroshima] dehumanized in my mind throughout the war, thinking of them as one vast, massive enemy, not human, not like any of us," wrote Hatfield. "Now on their shore, I knew the brilliant truth. They were exactly like us, suffering, afraid—human. Oh, so human. As the adults relaxed and smiled, as my lunch was completely given to the children, my loathing vanished. I stood awash, clean in an epiphany which has never deserted me. Hatred had gushed out, transmuted into the powerful balm of compassion." Before returning home, Hatfield sailed to Haiphong in Indochina, where he witnessed what he described in a letter to his parents as the "wealth divide between the peasant Vietnamese and the colonial French bourgeoisie." This he blamed on French colonizers, a conclusion that would later inform his contrarian stance on the Vietnam War.

Hatfield's rise to national prominence in the '60s and '70s as arguably the most important anti-war politician coincided with his elevation within evangelicalism, a point brought home by Swartz:

Despite his strong antiwar activism, Hatfield continued to be a welcome presence among many evangelicals. He traveled the evangelical circuit in the 1960s and 1970s, speaking at countless graduations and symposia. He served on boards of evangelical institutions and published books with evangelical publishers. Letters asking for donations to Hatfield's re-election campaigns circulated across the country in evangelical circles. He cultivated close relationships with Billy Graham, Bill Bright's Campus Crusade, InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, Carl Henry, and Christianity Today, and the Southern Baptist Convention. Such close ties suggest the presence of a liberal activist faction within establishment evangelicalism.

The Evangelical Left's influence on "establishment evangelicalism" in the 1960s and 1970s, through leaders like Hatfield, is an important part of the collective identity not only of American evangelicals, but of global Christianity as well. While in the United States the priorities of the Evangelical Left have taken a back seat to those of the Religious Right in recent decades, Swartz makes a compelling case, particularly in his chapter on the Latin American evangelical Samuel Escobar, that the Left's priorities remain latent in the global South. The dissonance between the priorities of the Religious Right in America and the priorities of global evangelicalism was symbolized by the 1989 Lausanne II conference in Manila. While the Evangelical Left in America was still licking its wounds from the Reagan Revolution, its impact on the global evangelicalism of the Lausanne Movement was deepening. With justification, Ron Sider could claim that the "holistic concern for both evangelism and social action" that defined his group Evangelicals for Social Action was the accepted mainstream of the Manila gathering.

Far From Dead

The resemblance between the social action agendas of the Evangelical Left in America and the evangelical mainstream globally is not an accident. As Swartz tells it, the shared vision is a result of decades of sustained, intentional interaction between individuals and institutions representing both groups. Within these circles, shared concerns over environmental degradation, economic inequality, consumerism, and racial divisions have existed for decades alongside profound commitments to world evangelization and Christ-centered witness.

Seen from a global perspective, then, the demise of the Evangelical Left in American religion and politics is an anomaly open to change as American evangelicals come into deeper communion with their brothers and sisters around the world. Far from being dead, Swartz suggests that the deep stirrings for justice and peace that burst into the mainstream of American evangelicalism in the '60s and '70s have impacted and been impacted by the "New Christendom" of the global South. It is precisely this possibility that makes Moral Minority not only a stirring account of recent American history, but also a necessary tool for understanding our global Christian moment. Buy it, read it, debate it, disagree with it, but do not ignore it.

Gregory Metzger is a freelance writer from Rockville, Maryland.