When Rowan Williams sits down to read his favorite books, he sometimes reaches for children's literature.

And the former Archbishop of Canterbury often chooses The Chronicles of Narnia, C. S. Lewis's best-known work. "Narnia is something that people do revisit," said Williams, who published The Lion's World in the UK last year (it came out in the U.S. earlier this year). "Children's books … are quite powerful tools for grown-ups' imaginations."

Perhaps imagination has been the secret to Lewis's growing popularity in the United Kingdom as the 50th anniversary of his November 22 death approaches. Though American evangelicals were quicker to admire Lewis as a literary hero, more and more UK intellectuals are now embracing him.

"It takes a while in Britain for a great man to be recognized as such," said Michael Ward, a senior research fellow at Oxford University and author of Planet Narnia. "But Lewis has been safely dead now for 50 years, and we can afford to recognize him as the major figure he was."

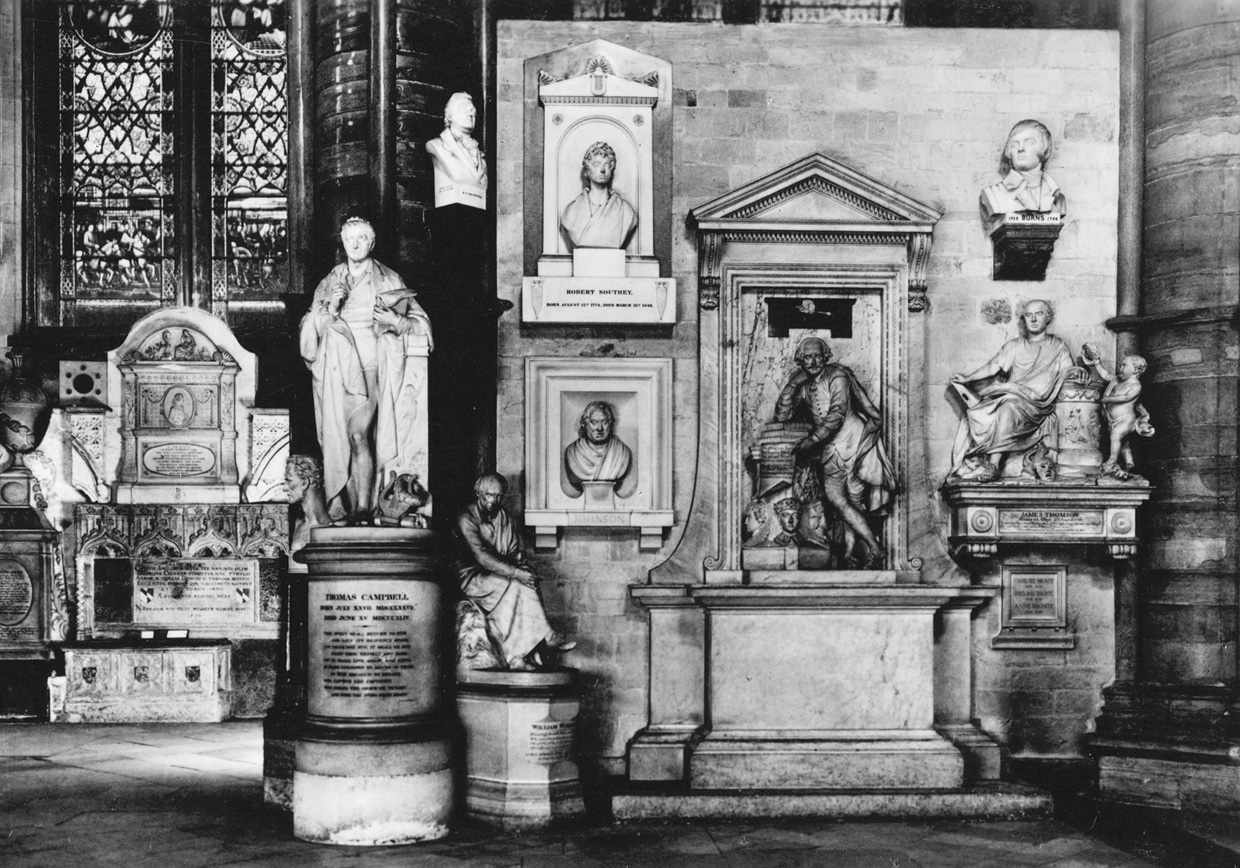

On the anniverary of his death, Lewis will be commemorated with a memorial plaque in Westminster Abbey's Poets' Corner, which honors authors and other cultural figures whose work has shaped English society. A two-day conference on Lewis's works will begin the preceding day.

Alister McGrath, the latest to examine Lewis biographically, believes this anniversary year will solidify Lewis's reputation as an apologist and classicist. At Oxford's recent literary conference, McGrath's sold-out talk on Lewis led to requests for him to give three more.

"We've minimized Lewis's importance [in the UK], and we have catching up to do [with U.S. evangelicals]," said the author of C.S. Lewis: A Life. "Lewis is here to stay; that debate is over. Now there is this sense of, 'There is more to learn from Lewis, so let's read him again.' "

This means reading more than Narnia. Lewis wrote across 13 genres, and his literary criticism is his best work, says Jerry Root, a Lewis scholar at Wheaton College.

Much of it was ill-received due to British faculties being "fairly aggressively secular," said Malcolm Guite, a Lewis scholar and a chaplain at Cambridge University. But he notes that Lewis's actual works of literary criticism never went out of print. Oxford University Press has three recently published books on the life and works of Lewis. Cambridge University issued its Cambridge Companion to C. S. Lewis in 2010.

These are signs that Lewis is becoming firmly established in British culture, said Ward. "Intellectuals are having to reckon with Lewis, even if they happen to find his Christianity unappealing."

But not everyone is so optimistic. Nick Spencer, research director for Christian think tank Theos, is skeptical that secular intellectuals will ever come to respect Lewis fully. Christianity's cultural despisers still pour contempt on Lewis, he said.

"[Lewis] is still certainly seen by some secular writers … as 'the great enemy,'" said Williams. "[Philip] Pullman's sequence of children's novels is meant as a deliberate counterblast to Lewis. But that's a backhanded tribute to Lewis's stature and influence, to say he's worth fighting."

Despite secular critics, the good news for Lewis is that UK evangelicals have gotten over their embarrassment about him, says Williams.

"Here is, by any standard, someone who is a serious intellectual … who thinks about the society we're in," he said. "It doesn't mean we have to agree with everything that he says. It does mean that we try to take him seriously." (See also our full interview with Williams on Lewis.)