Missionaries in South Korea—once the world's second-largest sender of such workers—can resume work in Yemen because their government lifted a travel ban this August. But four other majority-Muslim countries remain off-limits.

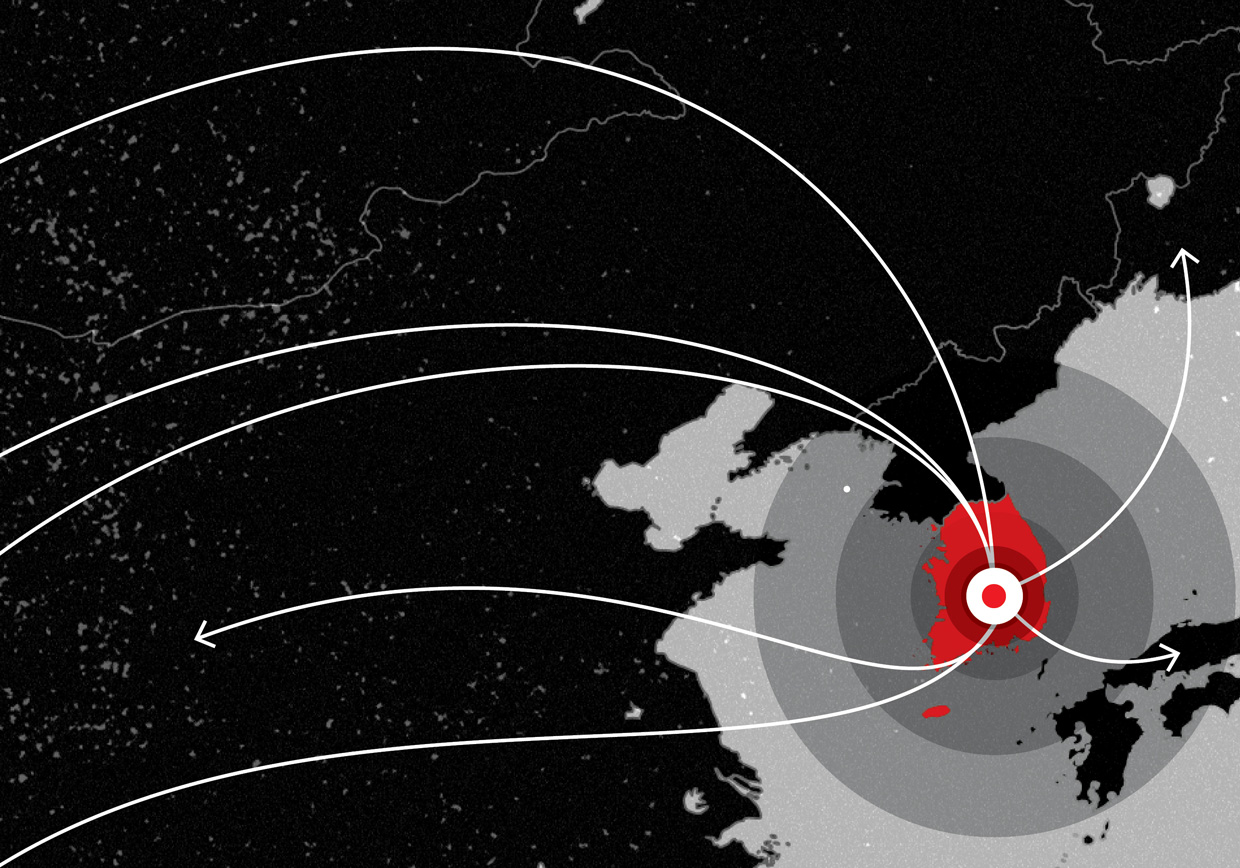

South Korea banned citizen travel to Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia in 2007, after Taliban operatives kidnapped 23 Korean missionaries in Afghanistan. The captors executed two before the missionaries were released. Travel to Yemen, Syria, and Libya was banned in 2011 (though the Libyan ban was lifted later that year).

Korean missions leaders have pushed to lift the bans, saying the government should grant greater flexibility to missionaries for their humanitarian work.

South Korea's government has been reluctant. "The duty of the government to protect its citizens is greater than the rights of a few ngos to go abroad for missionary activities," Chun Woo-seung, second secretary at the Foreign Ministry's Overseas Korean National Protection Division, told The Korea Herald.

Korea Crisis Management Service, a nonprofit launched after the 2007 kidnapping, has been editing a lengthy report on the hostage situation which will be released this fall to help churches avoid similar situations in the future, said Kim Jin-dae, its general director.

Dongsu Kim, a Korean professor of Bible and theology at Nyack College in New York, says some churches want the government to support missions work, while others want to work independently. Part of the challenge: the century-old Korean church has never navigated government-missionary relationships before, he said.

"Government learns, and churches learn, and they're on a learning curve," said Kim. "They will behave in a more mature way if the same kind of incident happens in the future."

The 2007 abduction, while tragic, prompted churches to beef up their crisis management and contingency planning, according to a 2012 report by Steve Sang-Cheol Moon, executive director of the Korea Research Institute for Mission.

The Korean missions movement has grown rapidly since the late 1970s, according to Julie Ma, a research tutor in missiology at the Oxford Center for Mission Studies. Today, 20,000 Korean missionaries are in the field, according to a recent study by the Center for the Study of Global Christianity (csgc).

South Korea also has one of the world's highest ratios of missionaries to church members: 1,014 (vs. 614 in the United States) for every 1 million members.

In South Korea, missionaries (many of them church planters) are sent out by nearly 60 denominations to 177 countries. The church currently ranks sixth worldwide in number of missionaries sent, falling from the No. 2 spot it occupied in 2006.

Moon believes this drop is due to churches sending only mature missionaries. This, he adds, corrects the aggressive recruiting of the past.

Donna Downes, professor of global leadership at Fuller Theological Seminary, agrees. "I don't think the change represents a decline in enthusiasm and vision as much as . . . an adjustment in pace and perspective so that the movement can mature," she said.

Meanwhile, the current travel bans could help focus Korean missions in areas where missionaries are more accepted and more likely to be successful, Kim said.

"Hindrance or persecution is not necessarily an obstacle, but the opening of a new door to different areas," he said. "The travel bans to those countries are unfortunate. But there are a lot more countries with no travel ban. There are no hindrances. Is it important for Koreans to evangelize all parts of the world?"