When you visit Life in Deep Ellum, the last word that comes to mind is "church." Directors Joel and Rachel Triska are just fine with that. They describe Life in Deep Ellum as "a cultural center built for the artistic, social, economic, and spiritual benefit of Deep Ellum and urban Dallas."

We saw the name of our organization, 'Life in Deep Ellum,' as a prophetic call. We wanted to bring life to a place in desperate need of it.

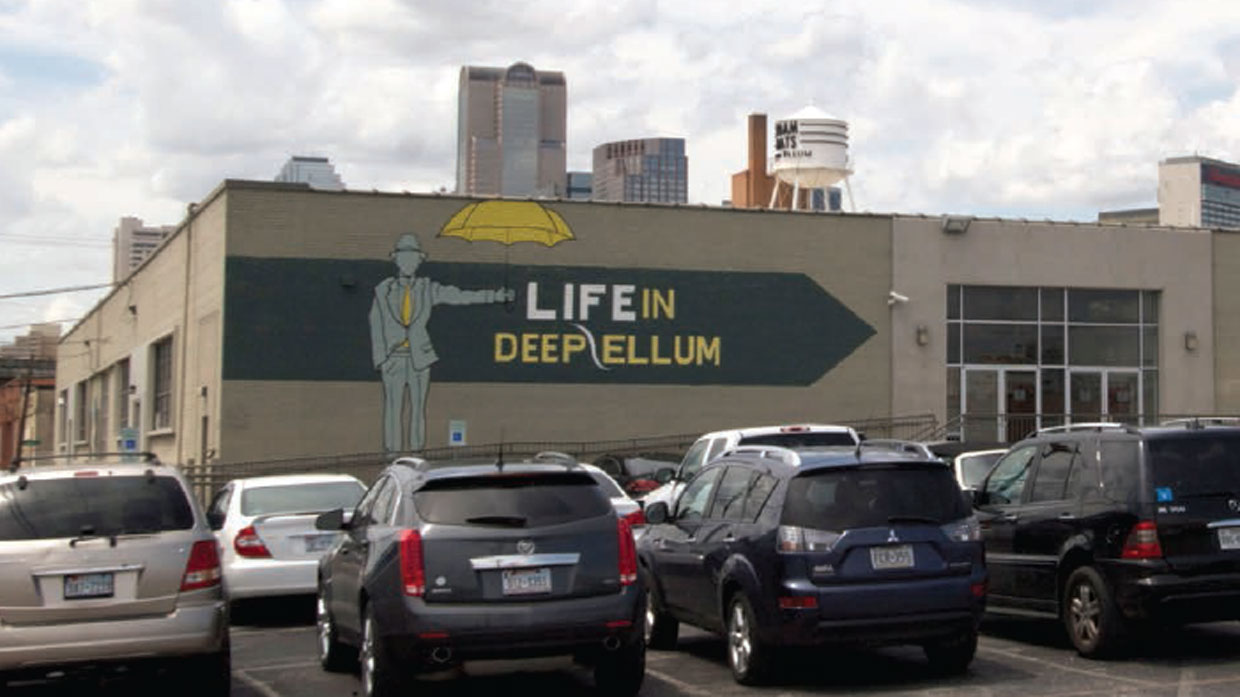

Housed in an industrial-style building in the heart of Dallas' artsy Deep Ellum district, the center is a veritable smorgasbord of creative culture. Walk through the front doors and you enter a stark gallery with avantgarde art. Turn to the right and you'll land in a coffee shop. This isn't your typical church coffee shop with a donation jar and a few carafes. Think Intelligentsia—dark ambiance, soft leather chairs, with baristas swirling amongst hissing machines.

Past the art gallery and down a hall, at the very back of the building, is an opening with wood floors and a small stage. It looks like the setting for an Indie rock concert (and sometimes is), but this is where their faith community meets at 11 a.m. on Sunday mornings.

Running a center with so many moving parts is a challenge, "like trying to hug a Sequoia," Joel says. But the holistic approach is central to their vision. Drew Dyck sat down with Joel and Rachel to talk about the unique ministry and what the relationship with their community can teach others.

How did Life in Deep Ellum start?

Joel: In the late 1990s and early 2000s Deep Ellum was thriving. The art and music scene were hot. It was the height of the punk and Goth scene. The streets were packed all night long. But around 2008 Deep Ellum suffered an economic crash. Bar after bar, music venue after music venue shut down. I remember a cover of The Dallas Observer. It showed an image of a tombstone with "Deep Ellum" etched in the stone. The message was clear: Deep Ellum was dead.

What was your strategy coming into a dying community?

Joel: We didn't just want to be a spiritual benefit; we wanted to address the community holistically. We saw the name of the organization, "Life in Deep Ellum," as a prophetic call of what we were about—bringing life to a place in desperate need of it.

Rachel: We hit the streets of Deep Ellum and did over 1,000 interviews asking people, "What would you miss if Deep Ellum was gone? What is your favorite aspect of this community?" Then we took all of those responses and narrowed it down to four things that residents really valued. It was art, music, community, and commerce. So we decided to build our cultural center and our faith community on those four pillars. We believed God was already at work and we wanted to get behind what he was doing.

How were you received initially?

Rachel: Some people were suspicious. They would ask, "Why are you doing this? What's your agenda?" We stressed that we didn't have one. Yes, we want people to come into a relationship with Jesus, but we wanted to simply underscore to our new neighbors that we were there to do life with them. We want to be a faithful Christian witness in a context that is very post-Christian. Our conversations are not driven by an I-have-to-get-this-person-saved agenda. We believe the Holy Spirit is a pretty effective evangelist.

Joel: We're just doing what any good missionary would do. We take time to learn the language and the customs of the people we're trying to reach. We build relationships, and we know that fruit is slow. We measure success very differently than a church in the suburbs. We're not reaching for low-hanging fruit. We know the fruit we're after is going to take years to grow. In some cases we will never even see what the seeds we plant become.

How do you measure success?

Joel: Our gold standard is community impact. How engaged are we with the community? How many community partnerships do we have? How many people are asking us to work with them? How many people from the neighborhood are regularly engaging with a Christian community? And how many people are we connecting with that would never engage with a Christian community otherwise? Right now we have a dozen community partnerships. Last year we had approximately 14,000 people come through the center.

Our conversations are not driven by an I-have-to-get-this-person-saved agenda. We believe the Holy Spirit is a pretty effective evangelist.

Rachel: We're far more interested in life change than numbers. A great example of this is our friend Will. When we met Will three years ago he would have identified as New Age. He grew up Catholic but was living with his partner of seven years. They had a child together. He's very involved in the art scene here in Dallas, and that's how we met him, through a partnership with an art group that he worked with. Over the last two years our partnership with him has grown.

He's doing this program called Diverse Lounge where he does workshops with at-risk kids. He teaches them how to express their stories through spoken word presentations. We have them in our center three or four times a year to have these huge celebrations with about 300 kids and they present their pieces. Will started as community partner, became friends, and then he started to office here. He began to be mentored by some of the Christian business people here. Then he started attending on Sunday mornings. In that process he and his wife got married and had a second child. Now he's deeply engaged with our community, and he would say that he's wrestling with Jesus in ways that he's never wrestled with him before. But I can't put him on the spectrum, this continuum. We really believe salvation is a process. There's no factory line.

What do things look like after someone becomes a believer?

Rachel: When people finally come to Jesus, we don't want them to point back to this moment when they said a pledge or signed a card. We want them to have a story to tell. Once someone begins to self-identify as a believer and they get baptized, then we start to measure. And at that point we measure spiritual growth and engagement. Are they being discipled? Are they going deep with community? And for us, community always means a group of believers and nonbelievers doing life together. We don't believe in discipleship that extracts people from where God has planted them. Rather you teach them how to follow Jesus right where they are. There's an artist in Deep Ellum that wrote a song we love to quote: "Fear of roots is fear of bloom." That captures our approach to discipleship.

Some churches would look at you guys and say, "Oh, we're doing all that. We have a coffee shop. We do drama." What's the difference?

Joel: We don't want to criticize all the churches that have coffee shops. But it is important to recognize that it's not just about providing coffee—it's the philosophy underneath it. A community-minded approach should affect your budget, how you structure staff, how you allocate resources. For example, our coffee shop is staffed mostly with people from the community and not people from our church. That's a crucial difference.

Rachel: The first church buildings were modeled after the Roman basilicas which were meeting places. It's where the greatest ideas were shared. Then it moves from basilicas to the cathedrals and then to the abbeys, which in their day were monuments to the best architecture and art. Fast forward to the chapels of the 1950s, and the value there was a simpler faith for a simple time. Like it or not, when people think church they think physical building. Our buildings are an incarnation of our values to a watching world. And so when people who are outside of the faith look at our building, whether we like it or not, we are expressing to them what we're about. And when most people look at church buildings today they think, that's not for me.

You have a unique setup here. But how can an average church, without this kind of space, be more engaged with their community?

Joel: There are two questions any church should ask, no matter if they're rural, urban, suburban, traditional, or edgy. Who can I partner with? And how can I resource the community? I've seen a lot of churches try to partner with their communities. They kind of stretch out and then snap back to the center, because the monster of maintenance is too demanding. Ultimately most church people are incredibly uncomfortable with their resources not going back to them.

We know the fruit we're after is going to take years to grow. In some cases we'll never even see what the seeds we plant become.

Rachel: We want to partner and resource what God is already doing in the community. If someone is helping the homeless, we're not going to say, "Let's start a homeless ministry." We're going to try and get behind what they're already doing. I think any church can do that. I think any church can go, you know what, instead of doing our fall festival this year we're going support the city's fall festival. Instead of doing our own Fourth of July fire-work celebration, we're going to give that money to the city and partner with them.

I love what Tim Keller's church does with giving grants to entrepreneurs. I think that's amazing. But when I read they only would fund Christian entrepreneurs, my heart broke a little bit. Why not open up the funds to outsiders and say, "We believe that God works through lots of people and we want to fund you, too." I think that would build relationships. We set aside money so we can invest in things that are completely unrelated to our work here. When we see God working in something, even if it's not through a group of believers, we're going to get behind what God is doing and get the community of faith involved.

But I think there's a psychological barrier there. It's hard to throw resources into something that is someone else's baby.

Joel: I think it all comes back to the metrics of success. What's really driving so many church leaders is this need to be successful by conventional standards. We're American to the core. If the credit is not coming back to us, if it's not bolstering our bottom line or increasing attendance, we think, why would it?

When people finally come to Jesus, we want them to have a story to tell.

Rachel: We had to wrestle with that. We were measuring success by conventional standards when we first came. And we felt like we were failing, despite all the great community partnerships that were forming. We had 50 at our first Sunday gathering and it grew to about 170. But we just didn't feel like we were getting to that level of success we expected. Now we look at things differently. We looked at the size of Deep Ellum and decided that if we ever get to 500, we will start planting other churches. At a certain size you start to lose effectiveness and just start feeding the beast.

Talk a little bit about the Sunday gathering.

Joel: We call our Sunday morning meeting The Gathering. Some come via the cultural center. So they've been to four or five events before they even realize there's a church here. Or they come through the coffee shop and they're looking around and think, There's something more going on here. And usually through conversation and relationship they make their way to The Gathering. They don't need to adapt much because they already get how we do things and why we do things. On the other hand, the person who Googles "downtown church" and finds us generally has a very difficult time adapting.

Rachel: Christians who come usually have a two- to three-month honeymoon with it. Initially they go, "This is fantastic. We love it." But that wears off. They have a hard time dropping the training they've received in other churches. They get uncomfortable with the fact that we don't make things easy, that our community is messy. And they worry that we're theologically liberal. People have a hard time believing innovation and orthodoxy can go together.

What would you say to someone who wants to try to emulate your ministry model?

Joel: We get pastors from all over the country who come through here seeing what they can copy. Some have said, "We want to do exactly what you're doing." My response was, "That means you need to shut down everything and start from scratch, because that's how we did it." Most people see what we're doing as being cool. They think that's the goal. "Oh, you have a gallery and a music venue." But the only reason we do those things is because they're connected to our context. So don't do what we're doing. Take some the principles of contextualization back to your community and do things that make sense there.

So you can't just copy; you have to contextualize.

Joel: Exactly. Too many people are looking for a plug and play thing. Sure, there are some of the things we do can be duplicated, especially our community partnerships. But the primary thing that I want people to think about is the philosophy, the principles. Of course that is a much harder conversation because it requires a lot more time and energy. I always caution people not to come back from a conference and think, I'm just going to take all these things and plug them into my church. It won't work. Even if you're being true to your context, it's probably going to be a couple of years before you start seeing fruit. Just start thinking like a missionary again.

Rachel: Look at your congregation. Who is a committed person who's there almost every Sunday, whatever metrics you use—the giving, they're involved in a small group—they do all that, but they refuse to be confined by the church programming. It's that guy who goes on fishing trips or hunting trips with his buddies four or five times a year, whatever it is that the people in your community do. Or maybe it's the woman who organizes a local food drive and is connected with the community. Whoever it is, find that person and get behind what they're doing. You'll be amazed at the new opportunities that arise.

Copyright © 2014 by the author or Christianity Today/Leadership Journal. Click here for reprint information on Leadership Journal.