Ridley Scott isn't the first filmmaker to tackle the story of Moses, and he certainly won't be the last. There's drama in the prophet's confrontations with the rulers of Egypt, there's spectacle in the miracles he performed to liberate his people, and there are lessons to be learned from the way he led the Israelites and forged them into a nation, not least by giving them the Law. And filmmakers have been turning to Moses’ story for inspiration since pretty much the dawn of cinema.

According to the Bible, Moses lived to be 120 years old, and people have been making movies about him for just about that long, now.

Some of the earliest movies about Moses were made in France: short films like Moses in the Bullrushes (1903), La Vie de Moïse (1905) and The Infancy of Moses (1911). In the United States, the American Vitagraph company produced a five-part series called The Life of Moses (1909–1910); each part focused on an episode from Moses' life, such as the parting of the Red Sea or the giving of the Ten Commandments, and because the complete series ran to about 90 minutes, some have called it one of the earliest feature films.

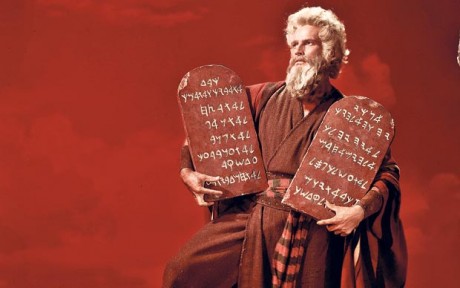

The biggest silent Moses movie of them all, however, was The Ten Commandments (1923)—not the famous remake with Charlton Heston, but the original black-and-white film. Like several other films in that period (such as Sodom and Gomorrah and Noah's Ark), The Ten Commandments combined a dramatization of the Bible with a modern story, and director Cecil B. DeMille lets us know the moral of that story right from the opening title cards, which chastise "our modern world" for calling the Ten Commandments "old fashioned."

The first 50 minutes or so are taken from the Bible, and show the plague of the firstborn, the Hebrews marching across the desert (in 2-strip Technicolor, a new format at that time), the parting of the Red Sea, the giving of the Ten Commandments, and the divine wrath that falls upon the Hebrews when they worship the golden calf. The film then segues to the "present day" and a story about two brothers who were raised in a religious home, one of whom rebels against his mother's faith and ends up suffering for it.

There were a few other Moses-themed movies after that, such as Moon of Israel (1924), an Austrian film that earned director Michael Curtiz a permanent job in Hollywood (where he went on to make such classics as Casablanca and White Christmas). But these were eclipsed by DeMille's 1956 remake of his own The Ten Commandments.

The remake, which was such a huge hit at the time that some people estimate it would still be one of the top-grossing films of all time if we adjusted for inflation, differed from the silent film in that it took place entirely in the ancient world and did not tell a modern story.

But it also created an elaborate fictitious storyline around Moses' experience as a prince of Egypt—a period in his life about which the Bible says almost nothing.

In that early part of the film, we see how Moses intuitively follows the commandments even though he has not received them yet; for example, he gives the slaves a weekly day of rest. Moses' basic decency stands in stark contrast to the jealous, power-hungry manner of his rival prince Ramses, and the fact that Moses can follow the commandments even though he doesn't have them yet (a la Rom. 2:14–15) underscores DeMille's belief that the Ten Commandments are not just religious laws but fundamental moral principles.

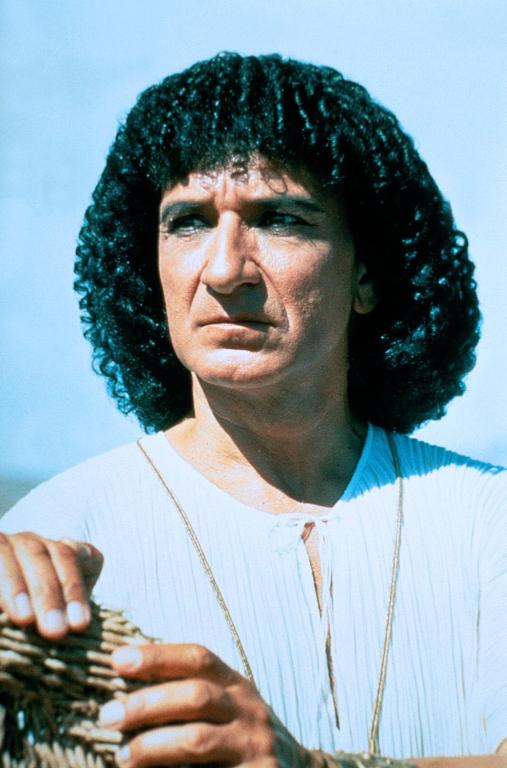

The Bible-epic genre more or less died out on the big screen in the 1960s, but it lived on, in less expensive form, in television. One of the longest treatments of the Moses story to date is Gianfranco de Bosio's Moses the Lawgiver (1974), a six-part miniseries produced by Vincenzo Labella and cowritten by Anthony Burgess, who would collaborate again a few years later on Franco Zeffirelli's Jesus of Nazareth. Unlike DeMille, whose films reached their climax with the giving of the Law and the worship of the golden calf, de Bosio follows the Israelites all the way through the 40 years of wandering in the wilderness.

Other TV productions have tried to pay more attention to what happened after the crossing of the Red Sea, too. Moses (1995), a two-part miniseries starring Ben Kingsley, and The Ten Commandments (2006), a two-part miniseries starring Dougray Scott, both put the crossing of the Red Sea at the middle of the story, as a cliffhanger at the end of the first episode—but where the 1995 film goes as far as the Israelites' journey to the edge of the Promised Land 40 years later, the 2006 film looks at how the Israelites grumbled against Moses and fought against the Amalekites on their journey from the Red Sea to Mount Sinai.

Parodies of the Moses story also followed the death of the Bible-movie genre. Wholly Moses! (1980) was a lame attempt to copy the formula set by Monty Python's Life of Brian: it concerns a Hebrew named Herschel (Dudley Moore) who keeps popping up on the fringe of Moses' story, just as Brian kept popping up on the outskirts of the gospels. In History of the World Part I (1981), Mel Brooks played a Moses who originally came down from Mount Sinai with 15 commandments, but then dropped and broke 1 of his 3 tablets.

The last major big-screen version of the Moses story was The Prince of Egypt (1998), which was also the first animated film produced by DreamWorks (though it was the second animated film they released, following a last-minute change to the release date of Antz). This was the first film to imagine that Moses and Ramses might have been friends at first, rather than enemies—a concept borrowed by Exodus: Gods and Kings (see CT's review)—and it was also one of the first major films in recent memory to aggressively court the faith-based market.

While the producers of The Prince of Egypt sought input from Jewish and Muslim consultants too, it seems fair to say, in hindsight, that their outreach to Christian leaders prefigured the marketing of The Passion of the Christ just a little over five years later, to say nothing of the "faith-based" marketing that now accompanies films like Noah on a regular basis.

For the most part, Exodus: Gods and Kings has downplayed its more explicitly religious marketing hooks. When the film was first put into development five years ago, it was billed as an action movie like Braveheart or 300; and after Ridley Scott became involved a few years later, everyone focused on the fact that it was from "the director of Gladiator." But the film fits into certain trends that can be traced across the Moses-movie genre.

Miracles

DeMille was quite happy to give a literal interpretation of the Bible's miracles. The 1923 version of The Ten Commandments even depicts a woman being healed of leprosy in the modern story, in imitation of the healings that take place in the Bible. But by the time he made the 1956 version, he felt the need to address modern skepticism on that issue.

In one scene, after several plagues have already happened, Ramses rejects the Egyptian and Hebrew gods alike and declares that the plagues were caused by purely natural forces: even though he saw the Nile turn to blood himself, Ramses now declares that red mud poisoned the Nile and caused the frogs and insects to leave the water and spread disease. Moses replies by predicting a hailstorm which cannot be tied to those other disasters—and it arrives within seconds. Thus the film acknowledges modern skepticism, only to dismiss it.

Later films, however, have been more ambivalent. In Moses the Lawgiver, various people speculate that the miracles might not be so miraculous after all—and when the Hebrews are trudging through the desert towards Sinai, Moses himself admits to Miriam that he knew enough about the migratory patterns of quail to predict that the Hebrews would soon be able to eat some. "A miracle, I suppose, is something you get when you need it," he says.

Exodus: Gods and Kings pushes modern discomfort with the miraculous even further, by omitting some of the miracles (such as the staff that turns to a snake) and assigning natural causes to all of the plagues except the final one. In this film, the Red Sea doesn't part; instead, a faraway meteorite causes a tsunami that first drains the water, thereby allowing the Hebrews to cross to the other side, before bringing it back with a vengeance.

However, Exodus just may be the only major movie about Moses that follows the Bible in depicting an angel at the burning bush (Ex. 3:2; Acts 7:30–38). Granted, the film shows Moses getting knocked on the head first, and it leaves open the possibility that Moses is hallucinating. But the boy Moses sees is called Malak, which is Hebrew for "messenger" or "angel," and through him Moses learns things he couldn't have known any other way.

Ethnicity

Most American or European films about Moses have cast white actors in the lead roles, but they have also tried, somewhat fitfully, to acknowledge the ethnic diversity of ancient Egypt and the universality of the biblical story through their supporting casts.

The 1956 version of The Ten Commandments, which came out as the American civil rights movement was gathering steam, featured an Ethiopian princess flirting with Moses, possibly as a nod to the statement in Numbers 12:1 that one of Moses' wives was a "Cushite."

A later scene is more ambivalent; at the first Passover, Moses welcomes the African men who serve as his mother's litter-bearers, saying there is room for "all who thirst for freedom”—but after entering the room, the men stand in the shadows, separate from the others, and when the Exodus gets under way, they continue to bear his mother's litter. The Hebrew slaves no longer serve anyone, but apparently the African slaves still do.

The Prince of Egypt aimed for ethnic accuracy in its depiction of the Hebrews and Egyptians alike, giving them Middle Eastern features. (The voices were largely Anglo, but of course they were redubbed by other actors in other parts of the world anyway.) And the 2006 version of The Ten Commandments cast Indian actors as Moses' adoptive mother and her son, while casting Egyptian actor Omar Sharif as Moses' father-in-law Jethro.

Exodus: Gods and Kings has been criticized widely for its "whitewashed" cast, which features actors of northern European descent as Moses, Ramses and a few other characters. But the film also features Iranian, Iraqi, Palestinian and half-Indian actors as members of the Egyptian nobility, including Ramses' wife and Moses' adoptive mother.

Violence

One of the questions everyone has to face when dealing with the Moses story is the violence: first the violence done to the Egyptians, including the firstborn and everyone who drowns in the Red Sea, and then—if the movies follow the story this far—the violence committed by the Hebrews against each other, sometimes at God's command.

DeMille largely skirted around these questions by portraying the victims unsympathetically or shifting responsibility for the violence. In the 1923 version of The Ten Commandments, Pharaoh's son is a brat whose death no one in the audience is supposed to mourn, while in the 1956 version, Moses warns Ramses that the next plague will be whatever Ramses decrees—so when Ramses decides to kill all of the Hebrew firstborn, God kills the Egyptian firstborn first. Later, when the Hebrews worship the golden calf, God punishes them with lightning and earthquakes, and not by sending the Levites to kill them at random.

Moses the Lawgiver keeps the more biblical, more violent version of the punishment (Ex. 32:25–29). It also shows Moses ordering that a man who was found gathering sticks on the Sabbath be stoned to death (Num. 15:32–36). The camera focuses not just on the man who dies in this painful way, but on the children who witness the stoning, and flinch.

Similarly, the 2006 version of The Ten Commandments shows Moses ordering the stoning of a couple who committed adultery and killed the woman's husband. (In an ironic twist, the adulterous man is the same man that Moses saved when he killed the Egyptian taskmaster.) Also, when the Hebrews are punished for worshiping the golden calf, it looks like all-out civil war—and when it's over, Moses says to kill the prisoners, because "it's God's will."

Exodus: Gods and Kings is similarly haunted by violence. Moses himself argues with God that the plagues are too extreme ("Is that it? Are you done?"). In the end, the film takes its cue from DeMille and suggests that killing the other side's children was Ramses' idea before it was God's. But then, when Ramses' firstborn son dies, he shows the body to Moses and asks, "What kind of fanatics worship such a God?”—and it's not hard to imagine director Scott, who self-identifies as atheist or agnostic, asking that same question.

The Law

Most movies acknowledge, to one degree or another, that it wasn't enough for Moses to set his people free from slavery; he had to give them a Law that would guide them as they forged a new nation, free of taskmasters telling them what to do.

The Prince of Egypt, which devotes only one or two shots to Moses bringing the tablets of the Law down from Sinai, may be the briefest expression of this. Other films go further. Both of DeMille's films juxtaposed the giving of the Ten Commandments with the Hebrews' worship of the golden calf, to underscore both the need for the Law and the perils of breaking it.

But where DeMille made a point of showing that it was possible for Moses to be a good man before he became a Hebrew prophet, Moses the Lawgiver and the 2006 version of The Ten Commandments devote entire scenes to Hebrews behaving badly before and after they leave Egypt, to show that they needed the Law and perhaps even its harsh enforcement.

Exodus: Gods and Kings is mostly concerned with the Hebrews securing their freedom, so it doesn't devote much time to the giving of the Law. But it does have a key scene near the end in which Moses asks what will become of the Israelites once they get to the Promised Land. And it ends with Moses carving out the Ten Commandments, as God tells him, "A leader can falter, but stone will endure. These laws will guide them in your stead."

And so Scott's film, for all of its deviations from the biblical story, fits into a number of trends that can be traced across cinematic interpretations of the Exodus. Time will tell whether it influences later films, the way that other films seem to have influenced it.

Peter T. Chattaway lives in Surrey, BC and blogs about film at Patheos. His earlier essays on Bible films for CT Movies include "Top Ten Jesus Movies," "Mary Goes to the Movies" and "The Genesis of 'Noah'."