Father Pawn Shop.

It doesn’t quite have the same ring as Father Christmas, but it’s an equal descriptor of St. Nicholas. We associate ol’ St. Nick with tinsel and chimneys, not money-lending and neon signs. We imagine him giving gold coins to hungry families, rather than purchasing gold at a fraction of its worth.

Yet St. Nicholas holds an unlikely affiliation with montes pietatis, the 14th century precursor to the modern-day pawn shop industry. At these early pawn shops, people in poverty met caring friars, there to help the poor get back on their feet. The shops were an outlet for Christian charity and Christmas generosity—hardly the kind of seedy business we think of today.

Pawn Shop History

In the Middle Ages, montes pietatius were charities similar to urban food banks. They provided low-interest loans to poor families, ensuring there was enough food on the table. Started by the Franciscans, who opened more than 150 of them, montes pietatius became widespread throughout Europe. In 1514, even Pope Julius II gave an edict endorsing these institutions, which had become the lifeblood of poor European peasants.

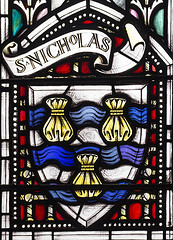

According to folklore, St. Nicholas generously provided a man in need dowries for his three daughters, gold coins in three purses. The symbol of gold coins in three purses became the symbol of pawn shops and fit with his title of patron saint. We celebrate St. Nick because he is a generous giver, and now, it seems incongruous the very symbol of his generosity remains the icon of modern-day pawn shops.

Dotting rundown strip malls, often in rough sections of town, pawn shops symbolize desperation rather than generosity. These are places of last resort for people fraught for cash. Unlike the gentle friars, pawn shop owners thrive at the expense of their customers, regularly victimizing the vulnerable men and women who walk through their front doors.

Although they have existed for centuries, pawn shops are surging in notoriety, but with no trace of their benevolent purpose or founding.

Celebrity Pawning

In 2009, the first episode of Pawn Stars debuted on the History Channel, quickly becoming the channel’s most-viewed show. Now in its ninth season, it is a mainstay of cable television, once ranking as the second most-viewed reality television show on cable, averaging over 5 million viewers a week. The proof of its success is in what it has spawned. Today, a half-dozen spinoffs and copycat shows like Pawn Queens and Hardcore Pawn stream on channels from TLC to Discovery to truTV.

The shows thrive on the big personalities of pawn shop owners and the unique keepsakes sellers bring into the stores. In some cases, sellers bring in their oddities with the hopes of walking out the door with cash. But more commonly, the sellers treat the pawn shop as a safe deposit box. They bring their wedding rings and antique coins and walk out with cash, hoping to return on a brighter day to buy back their stuff.

The untold story woven through these shows is the desperate states of many of the patrons. We’re drawn into the negotiation, the craziness of the items (a 13th century crossbow? Really?), and the predictable reality show drama between the shop employees. But just beneath the sheen is a wrenching reality.

On a recent episode of Pawn Stars, the owners of the Las Vegas outfit entertained a man aiming to sell a coin minted in 1861. The seller hoped to pocket a few thousand dollars from his valuable, but eventually accepted an offer of $400, much less than half what he had hoped to earn. “Well, you’re really hurting me. My wife spends more than that at the casino,” he lamented.

Nearly 80 percent of pawn shop customers take out multiple loans each year, and pawn loan defaults are on the rise. Most pawn shop customers survive on very low incomes; 20 percent of them are unemployed. Many sellers are grateful to find a business willing to give cash for their stuff. But for more, pawn shops are not a place of respite and hope, but bankers for people on the brink of collapse.

The Underbelly of the Pawn Industry

There are merits to the industry. These shop owners do business with many vulnerable segments of our population. The Pawn Stars website notes the history of pawn shops and suggests that “pawn shops are still helping everyday people make ends meet.”

It’s a half-truth. Pawn shops do help people make ends meet in the short-run, but these transactions often end up hurting their customers more than helping. Rather than benefiting the sellers, they victimize their customers and act like a high-interest credit card for the vulnerable.

When a seller brings in a piece of jewelry, for example, the jewelry acts as collateral. The “pawn” stays with the shop owner and the seller walks out with a commensurate wad of cash. The seller has a few weeks to come back and buy back the pawn—plus interest. Or, they can extend the terms.

And this is where the industry’s morals drift into murky territory. For shop owners, they have every incentive to keep the product on loan to its owner. Often, pawnbrokers charge annual interest rates equivalent to more than 300 percent. Brokers market the loans as short-term, but in many places they are anything but, trapping sellers in an unenviable cycle of debt where they’re forced to pay exorbitant sums of interest to recapture their valuables.

“They're scum-sucking bottom feeders. These people are horrible,” wrote financial guru Dave Ramsey, on short-term lenders like pawnbrokers and payday lenders, describing them as “designed to take advantage of lower-income people and benefit only the owners of the companies making the loan.”

Like Ramsey, Christians ought to speak out against predatory lenders like pawn shops. And, some Christians have responded even more aggressively. A number of urban ministries and churches have launched counter initiatives to help those trapped under the burden of debt and provide alternative ways to provide for short-term emergencies.

From Charity to Usury

Over time, pawn shop owners lost sight of their identity. Created for good, pawn shops have drifted away from their purpose. From caring for the needy to an instrument often preying on families in distress, pawn shops have lost their original intent.

It’s hard to reconcile the image of humble clergymen helping hard-up peasants seven hundred years ago to the loud neon shops advertising quick and easy cash for jewelry and coins and treasured family keepsakes. Today’s pawn shops feel nothing like the descendants of montes pietatius. They feel like the archenemies.

The slow, steady mission drift at these institutions typifies a pattern found in higher education, in denominations, and even in our own marriages and faith journeys. Often unintended and unforeseen, pawnbrokers over generations have simply forgotten their reason for existing. They’ve drifted so far they no longer resemble their founding vision.

The legend of Kris Kringle starts with the generosity of St. Nicholas. The cherished saint isn’t remembered solely for his holiday giving. He also stands for the creative efforts churches have undertaken throughout history to care for those in need.

As many in the pawn shop industry have lost sight of their mission entirely, it provides an opportunity for Christians to recapture the spirit of montes pietatius, to speak out against moneylending and provide safe and transparent financial alternatives to families in need. This is the way to celebrate the generosity and true legacy of St. Nick.

Peter Greer and Chris Horst are the coauthors of Mission Drift and Entrepreneurship for Human Flourishing and serve in leadership roles at HOPE International. Connect with them on Twitter, @peterkgreer and @chrishorst.