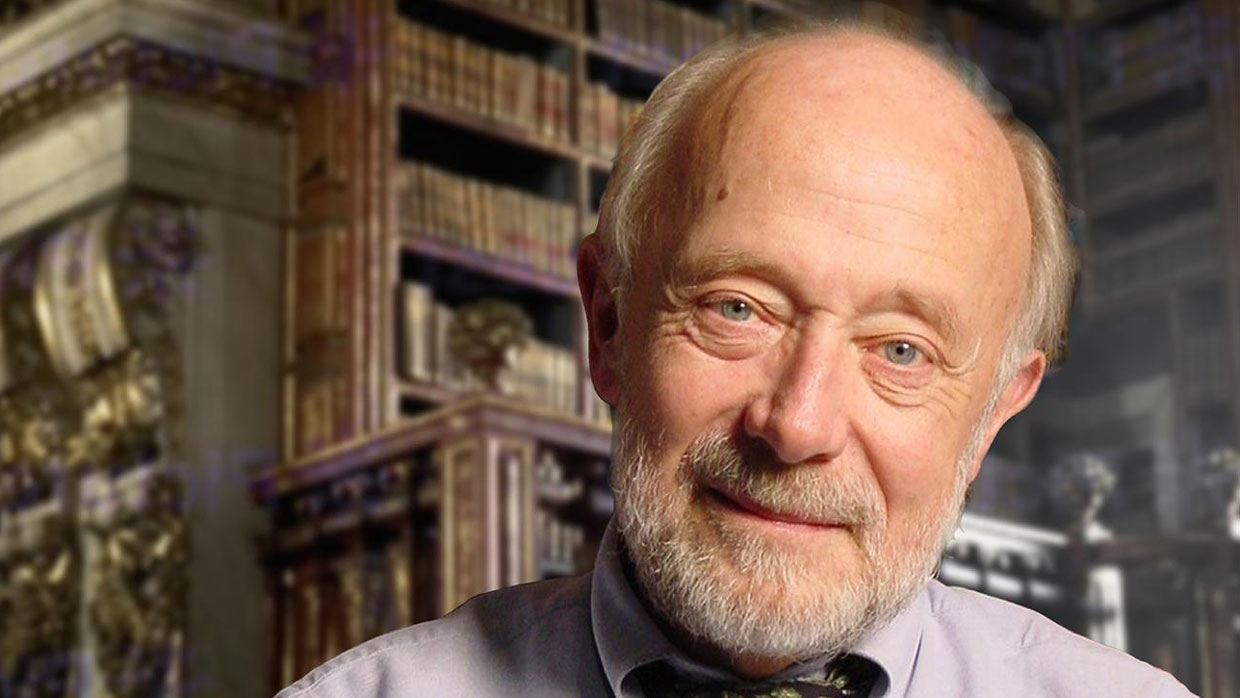

Marcus Borg, a liberal Jesus and biblical scholar, died on Wednesday, January 21, at 72 after suffering from pulmonary fibrosis.

Borg, along with scholars like Paula Fredriksen, John Dominic Crossan, and N. T. Wright, helped create a resurgent interest in the historical Jesus—a quest to retrieve a historically accurate portrait of Jesus—and for two decades shaped and reshaped its discussion.

Borg was a prominent leader of the Jesus Seminar, an effort to separate what Jesus scholars saw as fact from myth in the Gospels. Yet his work was “not so much a new departure in liberal study of Jesus as a repackaging and representation of seeing Jesus as a prophetic figure,” said Darrell Bock, senior research professor of New Testament at Dallas Theological Seminary.

Borg was especially interested in maintaining the Jewishness of Jesus—though not as the messiah—arguing that he as a prophet who wanted to replace Jewish holiness codes with an ethic of compassion. Following many liberal renditions of Jesus, Borg denied the historicity of the Resurrection. Yet unlike many Jesus scholars, he was sympathetic to the spiritual and the miraculous. For Borg, Jesus was a “spirit person” for whom the Spirit or God was an experiential reality. As a result, Jesus was “a mediator of the sacred,” offering an alternative vision of God and reality.

“To have someone who was a credible liberal theologian open the door to [the miraculous] was a way of softening the boundaries between conservative historical Jesus scholars and hard-line historical Jesus scholars,” said Nicholas Perrin, professor of biblical studies at Wheaton College.

Borg was also occupied with preserving Jesus’ political agenda. “Borg’s concern was a Jesus who spoke for social justice,” said Craig Keener, professor of New Testament at Asbury Theological Seminary.

This aspect made Borg’s vision of Jesus all-encompassing, said Perrin. “He brings together a social-political vision with a personal-religious vision. Very few historical Jesus scholars combine those two things,” he said. While evangelicals disagree with Borg’s full account of Jesus, “we should thank Borg for forcing us to take seriously Jesus as a political thinker,” said Perrin.

Indeed, evangelical scholars disagreed with Borg on many points—historical, exegetical, and theological. Bock said, “Borg was Bart Ehrman before Bart Ehrman came on the scene. Most evangelicals who interacted with Borg did so in order to respond to the kind of doubts he introduced about Scripture and its portrait of Jesus.”

But Borg was nonetheless esteemed as a respectable scholar and valuable dialogue partner. “He was the kind of scholar one could not and did not want to ignore,” said Scot McKnight, professor of New Testament at Northern Seminary. “He patiently listened to all sides of the debates and knew the strengths of evangelicalism and historic orthodoxy, even if he pointed more often to weaknesses. Borg was the kind of progressive/liberal theologian who welcomed evangelicals to the table—as long as they would listen, as well.”

Moreover, McKnight considered Borg a “pastor.” And Ben Witherington III, professor of New Testament at Asbury Theological Seminary, described him as a “Christian churchman.” (Borg was the first canon theologian at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Portland, Oregon.) “Most of his published work was geared toward educated lay persons and clergy, books he hoped would get them to engage with serious ethical and theological matters, including with the Bible itself,” he said.

Craig Blomberg, professor of New Testament at Denver Seminary, said Borg was motivated by the conviction that “classic approaches to Christianity couldn’t handle all the contemporary challenges of the secular world. In many ways, he was trying to be for our age what Friedrich Schleiermacher, with his book On Religion: Speeches to Its Cultured Despisers, was trying to do in the early 1800s.”

While Borg was often controversial, he was not a curmudgeon or obnoxious about his views, said Witherington. “The church has lost a friendly dialogue partner,” he said, “and in an age where dialogue has degenerated into posturing, shouting, and not really listening to one another, this is a great loss indeed.”