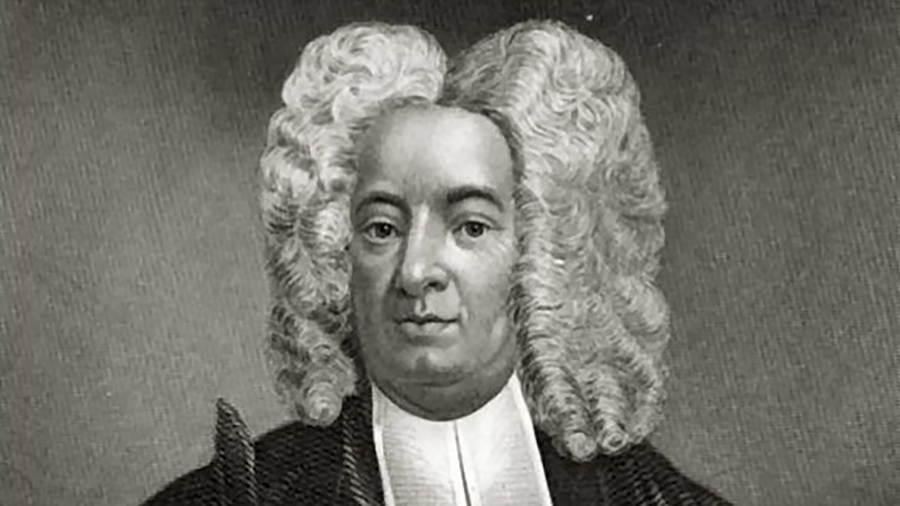

If we remember the Puritan pastor Cotton Mather at all these days, we’re likely to think of him as a meddling, moralistic hypocrite. To the contemporary mind, Mather (1663–1728) was more concerned about his own reputation for intelligence and piety than about the Salem people killed for “witchcraft” on his watch, or the slaves held in bondage in his hometown of Boston.

The First American Evangelical: A Short Life of Cotton Mather (Library of Religious Biography (LRB))

Eerdmans

176 pages

$15.99

But Rick Kennedy challenges this portrayal in his lively new biography, The First American Evangelical: A Short Life of Cotton Mather (Eerdmans). Kennedy, a historian from Point Loma Nazarene University, argues that Mather was more socially progressive than his reputation suggests.

Mather knew his share of suffering. Picked on as a child, he stuttered for years—a painful thorn in the flesh for an aspiring preacher. He buried 2 wives and 13 of his 15 children. But he rested on the promises of Scripture, compensating for hardships by edifying others. He undertook pioneering efforts in public education and ministry to prisoners, widows, orphans, slaves, and sailors. His congregation loved him dearly, as Kennedy writes, “for exuberantly modeling a lively relationship with Christ that was grounded in the Bible.” Mather’s Old North Church would remain a beacon of Christian faith and practice long after his death.

Historians often picture Mather as the last of the Puritans, a backward-looking Calvinist who chafed at modern life. In Kennedy’s telling, however, Mather emerges as a forward-looking man of formidable learning, a warm-hearted herald of pure and undefiled religion, and a major catalyst of Britain’s “biblical enlightenment.” By the late 17th century, New England was outgrowing its narrow Puritan identity. Its leaders were warming to the wider Protestant world and collaborating with British coreligionists to check the progress of Catholic France. Mather joined in this campaign, forging partnerships with a wide range of European preachers and theologians. But he worried about the shallow, spiritually tepid faith that all too often shadowed the campaign’s cosmopolitan ambitions.

Kennedy clearly admires Mather. This is a breath of fresh air at a time when Christian scholars occasionally treat their kin with an air of superiority or a hint of irony. Kennedy overreaches in tracing modern American evangelicalism to the work of one man. But he’s right to remind readers how Puritanism and European pietism would shape the movement to come.

The book can be guilty of obscuring Mather’s personal failings. It seems ill-advised, for instance, to gloss over Mather’s complicity in the persecution of “witches” and the enslavement of Africans. But Kennedy introduces valuable evidence casting his subject in a friendlier light. He demonstrates that Mather urged caution to Salem’s civic leaders, called for loving, personal ministry to those accused of witchcraft, spoke out against the slave trade, and eventually permitted his own slave to buy his freedom. Mather has languished so long in the pillory of modern indignation that we’ve lost sight of what he can teach us about ourselves and our own struggles.

The First American Evangelical offers a great feel for Mather’s vibrant, quirky, and learned spirituality. It is full of wisdom. Indeed, the book shows what we can learn from historic Christian leaders when we humble ourselves and heed them not as spotless saints, but as flawed mortals—just like us—who sought to do the best they could with the gifts they received.

Douglas Sweeney teaches church history at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School.