Alissa’s note: Ken Morefield, a longtime contributor to Christianity Today Movies and a cinephile and critic for whom I have great respect, writes a post we call “The Long Tail.” Each month, he looks at a few films that are being primarily distributed to American audiences through DVDs or Internet streaming and tries to surface some movies that might otherwise fly under the radar.

If you’re worn out on on comic-book films and bubble gum blockbusters, you may be ready to scan the lists of DVD and streaming releases for less flashy fare. September offers some great options, unified by a common theme: individuals who are both shaped by their communities and trying to influence them.

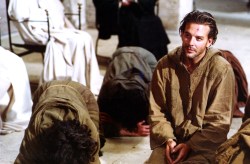

Francesco: St. Francis of Assisi

Film Movement

Film MovementFilm Movement kicks off the month of September with a Blu-ray reissue of Liliana Cavani’s powerful and affecting Francesco—a biography of St. Francis of Assisi. On paper Cavani, best known for the controversial sadomasochism-themed The Night Porter, would seem an odd choice for this project.

And Mickey Rourke, coming off of Nine ½ Weeks, Angel Heart, and Barfly, would not have been among the first fifty actors I would have imagined playing the iconic saint. The casting turns out to be inspired, though. He is riveting.

In fact, the whole film is remarkably engaging. It may take fifteen minutes or so for American viewers to adjust to the artificiality of the dubbing and the less-emotive acting style common in many European films. But stick it out. This biopic carefully imagines the psychological and spiritual toll (paid by both Francis and those who love him) of the saint’s attempts at simple obedience to God’s words. An early scene where Francis’s father pleads before the court while his son renounces all claims to the family’s wealth is devastatingly painful in its archetypal power. So too is Francis’s loneliness in the face of a suspicious church structure and followers who would prefer rules rather than principles.

Those sensitive to nudity should be warned that there are a couple of non-erotic scenes of the undraped human form, including one where Francis crawls naked through the snow. There is also a brief glimpse at a human body being flayed that is not for the squeamish. My only real complaint was the Vangelis soundtrack, which felt oddly triumphal amidst so many sober scenes.

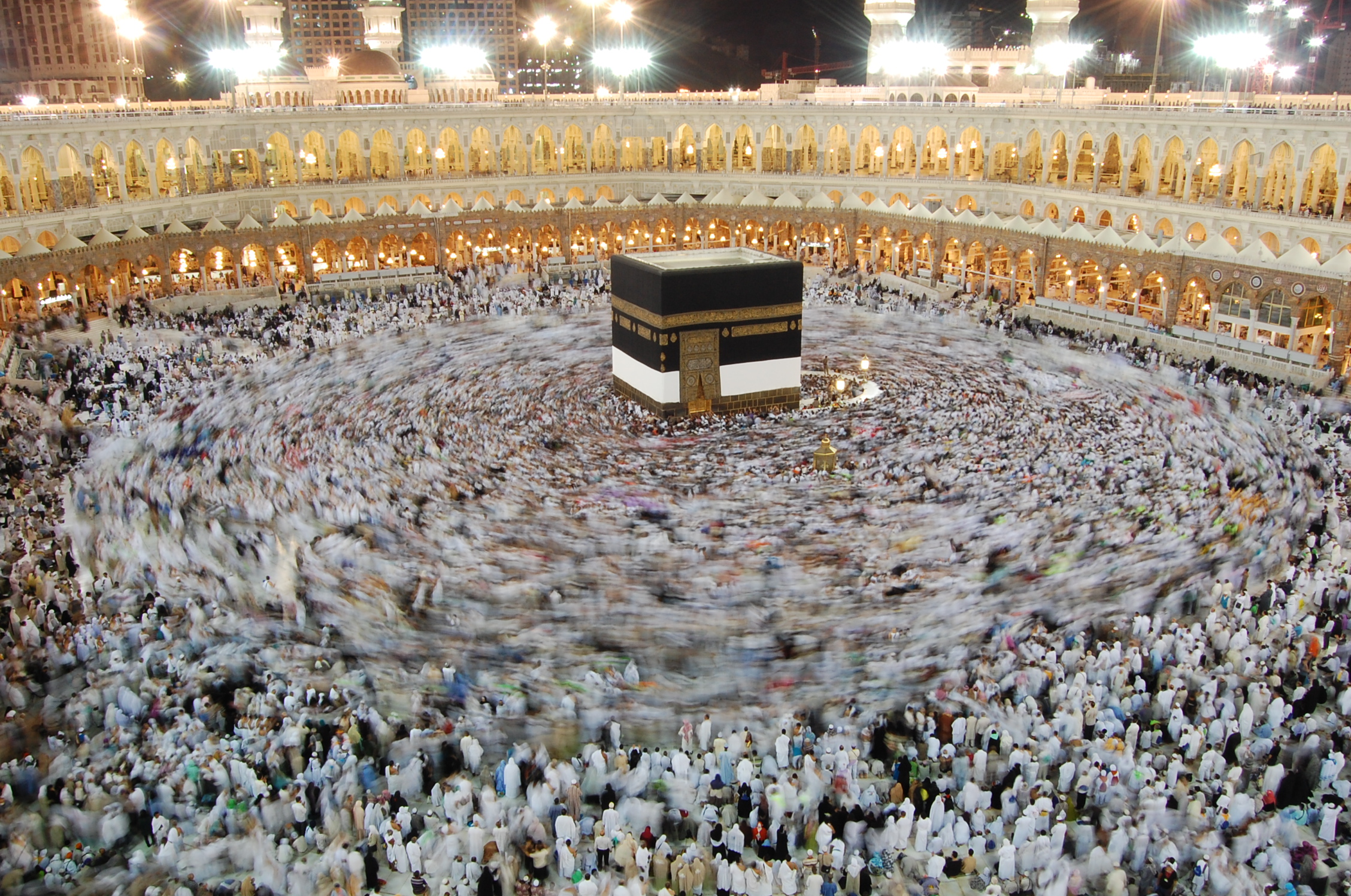

A Sinner in Mecca: Critical But Not Mocking

Haram Films

Haram FilmsParvez Sharma’s A Sinner in Mecca tells the story of a very different struggle between a believer and his religion’s power structure. Sharma, an openly gay Muslim, attempts to film his Hajj pilgrimage, traveling to a land where the penalty for being found gay is death. The risks he is taking are underscored by footage he receives and shares early in the film of a suspected gay man being beheaded in Medina. Another gay man who witnesses the execution and chats with Sharma online says, “I am so f—ing afraid all the time.” Of life in Saudi Arabia as a gay man, he says simply, “It’s HELL.”

Sharma’s documenting of his own (gay) marriage and lamentations about his family’s rejection will probably sound familiar to any Christians who have even a cursory familiarity with gay film or literature. (His mother’s rejection was particularly painful.)

What sets this documentary apart, though, is the footage Sharma takes on the Hajj, often in areas where non-Muslims and filming are forbidden. His alienated status makes him sensitive to the ironies or paradoxes of his journey: a Starbucks seven hundred meters from one of the holiest sites in his religion, the trash-lined streets of a tent city, a report of a woman being fondled lecherously amidst the crowds of pilgrims.

Sharma is critical but never mocking; he wants to be reconciled with the religion that wants no part of him. His willingness to place his own body in danger helps us catch glimpses of people and places most of us would otherwise only know by report.

Welcome to Leith: Pluralism and Principle

First Run Features

First Run FeaturesEqually conflicted and maybe equally scared are the citizens of Leith, South Dakota, in First Run Features’ Welcome to Leith. In 2012, a man by the name of Craig Cobb entered the community and began buying up plots of cheap land. The citizens didn’t know him, but the Southern Poverty Law Center did.

Cobb is one of America’s most well-known White Supremacists, and his plan was to invite others who shared his views to congregate in the small town (three square miles, twenty-seven residents), hoping to attract enough of them that they will form a plurality, and thus be able to take over the reins of government.

Welcome to Leith is many things, including a story of ordinary people confronted, face-to-face, with attitudes and practices they can neither abide nor understand. Heading into an election year, it is also a fascinating test case for thinking about how we deal with threats to our community and our way of life, on the broader (national or international) scale. Town council meetings are disrupted by Cobb and his confederates’ confrontational rhetoric and incessant filming. (In a previous case, Cobb had once posted the personal address of a judge whose decision he did not like.)

Leith responds by passing laws directly aimed at getting the unwelcome immigrants off the land and out of the town. Citizens more or less admit that a bill mandating that every plot of land where people are living have running water is constructed not out of health concerns but as a means of targeting the unwelcome.

First Run Features

First Run FeaturesThe irony here is that these sorts of legal maneuvers have historically been used to disenfranchise minorities. It is either an irony lost on the Southern Poverty Law Center or one which they choose to ignore. When Cobb is eventually arrested for “terrorizing” the community, one of the complaints has to be dismissed because a citizen admits he only claimed to be in fear of his life because that is what law enforcement told him he had to say in order to get Cobb arrested.

It is hard to stick to principle and procedure when you are in fear. Must democracy afford rights and protections to those who would deny the same to others if and when they seize power? Must those who insist on their right to own a firearm wait for their crazy neighbor to kill somebody before they take away his?

The film doesn’t sympathize with Cobb; it uses him to force us to grapple with these and other important questions. How much liberty are we willing to sacrifice to feel safe, and must we give the devil the protection of law even when doing so puts our own lives in danger?

Don Matteo: A Priest in Italy

MHz Home Entertainment

MHz Home EntertainmentFor those wanting slightly lighter fare, MHz has made available two new DVD sets of the delightful Italian show, Don Matteo. Each set contains twelve episodes of the procedural, with Terence Hill as a Catholic priest in Gubbio. The mysteries are seldom complicated, but the simplicity of the plots is endearing. Matteo generally solves crimes more as a result of careful observation and attentive presence than acute deduction.

In the series’ pilot episode, the priest comes to the aid of a falsely accused Muslim and urges the actual guilty party to confess for his soul’s sake. Matteo is handsome and humble—his supervisor urges him to wear a cassock instead of a suit—and as he bicycles from location to location the show makes ample use of the gorgeous Italian countryside. Hill also infuses Matteo with an affable gentleness.

The Italian crime solver is quickly becoming one of my favorite fictional priests because of the way he acts as salt and light for the whole community, not just other Catholics, in the course of his duties.

Kenneth R. Morefield (@kenmorefield) is an Associate Professor of English at Campbell University. He is the editor of Faith and Spirituality in Masters of World Cinema, Volumes I, II, & III, and the founder of 1More Film Blog.