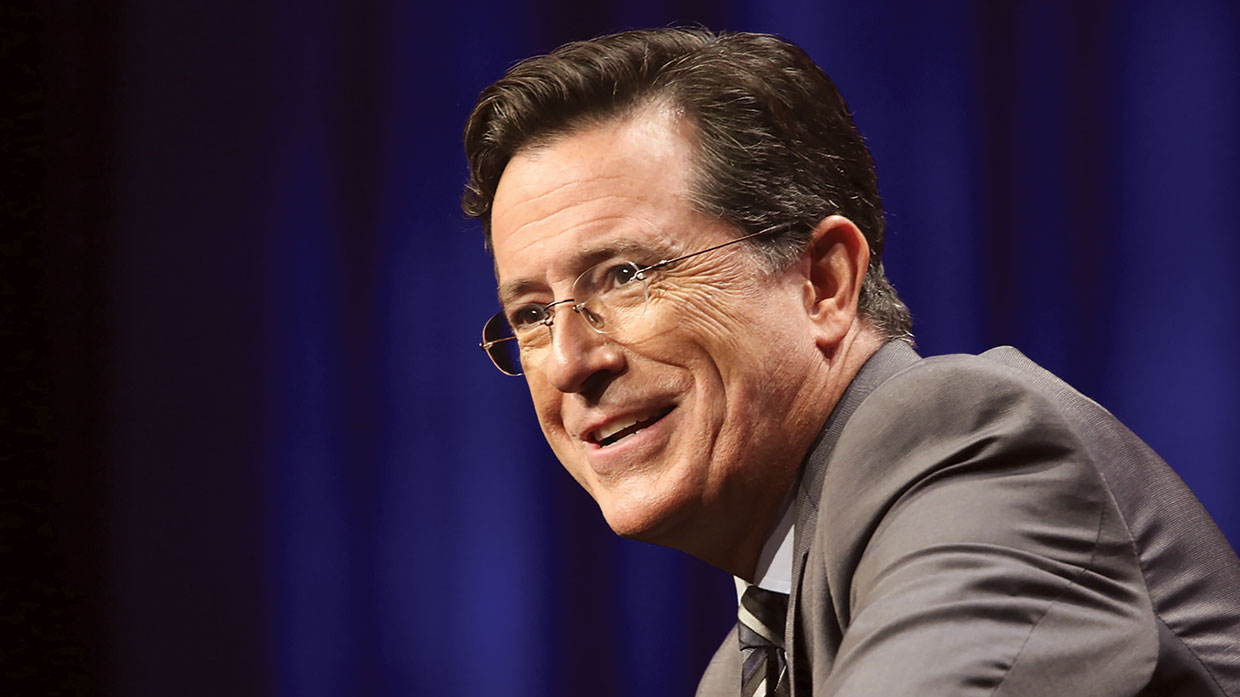

Comedy often emerges from lives marked by tragedy, and new Late Show host Stephen Colbert is no exception. In a cover story for GQ, Joel Lovell described Colbert’s difficult childhood—growing up the youngest of eleven kids, losing his father and two closest brothers in a car crash when he was 10, struggling academically—all preceded his impressive climb to comedic stardom.

Colbert cites his faith (he’s a practicing Catholic) as an expression of the gratitude and joy that’s contributed to his success. “I’m very grateful to be alive,” Colbert says. “And so that impulse to be grateful, wants an object. That object I call God.”

His relentless gratitude, in fact, is what helped him overcome his family’s loss. Quoting a letter from J.R.R. Tolkien, Colbert asks, “‘What punishments of God are not gifts?’ … It would be ungrateful not to take everything with gratitude.” That dogged pursuit of joy has made him one of the most successful innovators and leaders in American entertainment.

Profanity’s Changing Tone

We all know of Paul’s imperative that we put away obscene talk, but what if cultural definitions of obscenity change? In “How Dare You Say That! The Evolution of Profanity” in The Wall Street Journal, linguist John H. McWhorter traced the development of profanity from literal swearing of oaths in the medieval era (“By God!”), the reliance of euphemisms in the Renaissance (“Odsbodikins!”), and the growing discomfort with words about sex and excretion—all of which have contributed to our ever-evolving lexicon of “bad words.”

Context changes: words that used to qualify as “profane” are now merely “salty,” while others—particularly those involving “the slandering of groups, especially groups that have historically suffered discrimination or worse”—are considered taboo. This is good news to medieval literature expert Melissa Mohr, who sees the change as “a sign that culturally we are able to put ourselves in other people’s shoes a little bit more than we were in the past.” It’s something to keep in mind the next time you stub your toe. —Adam Marshall

In Polls We Trust, Should We?

In a recent post on First Things, Princeton professor Robert Wuthnow calls into question the value of religious polling:

“From the beginning,” Wuthnow notes, “polling was in the business to make headlines, and that is pretty much what it continues to do today. The seeming accuracy of results to the tenth of a percentage point doesn’t stand up to basic methodological scrutiny, nor does the content of the questions themselves. If the devil is in the details, the details about religion polls are devilishly difficult to trust.”

Copyright © 2015 by the author or Christianity Today/Leadership Journal.Click here for reprint information on Leadership Journal.