Many of the most pressing issues facing pastors today aren't new. Pastors throughout history have led churches through strikingly similar problems. Here are three examples.

Christianity in Exile

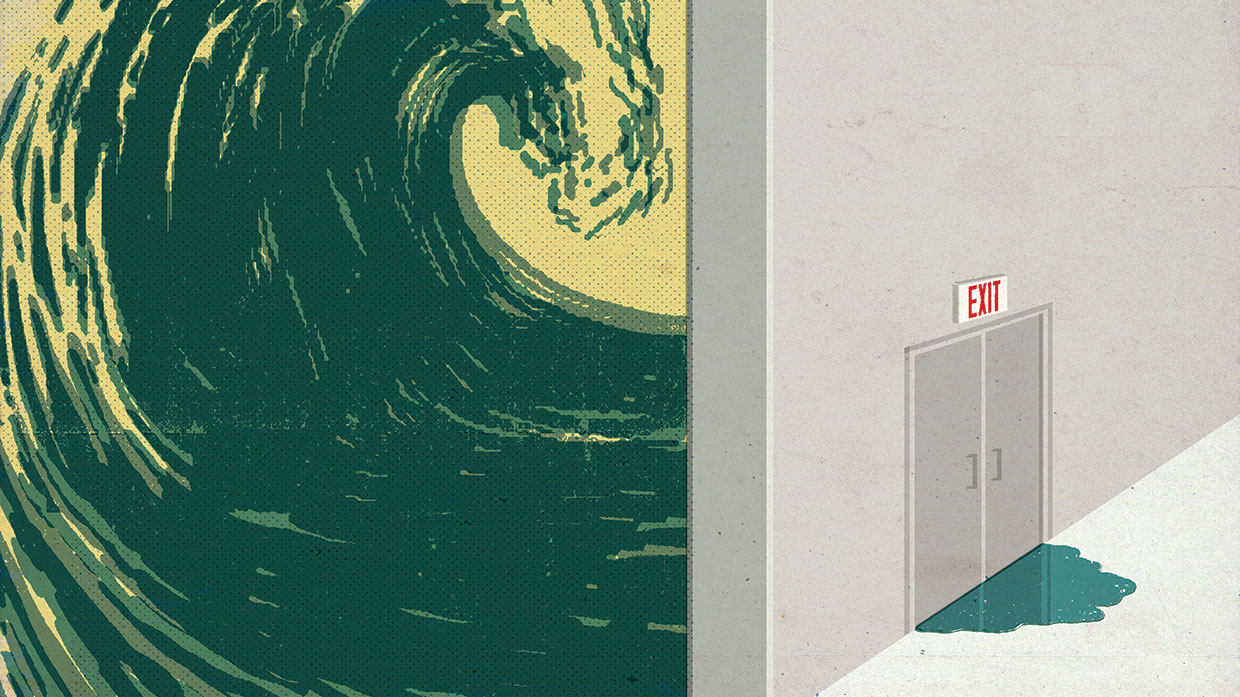

Christianity is losing its influence, at least in the West. The nation-wide legalization of gay marriage combined with lawsuits against Christian bakers and photographers who refuse to serve same-sex weddings have shown the cultural tide turning away from the influence of evangelical Christianity. Politicians cater less to the wishes of evangelicals, and public figures spend more time scolding the church than listening to it.

There have been times when Christians enjoyed considerable social influence, like when Ambrose (337-397), the Bishop of Milan, impelled Theodosius, the Emperor of Rome, to repent for his unethical massacre of Thessalonians, threatening him with excommunication. Just a generation later, Ambrose's most famous protégé, Augustine of Hippo (354-430), witnessed serious shifts in Christianity's social prominence. In A.D. 410 the Goths sacked Rome, leaving the city in destruction, and causing the empire great despair. Christians and non-Christians alike were robbed, raped, and killed.

Pagans blamed the calamity on Rome's abandoning its gods for Christianity. Many felt tempted to return to idol worship for protection. Augustine had to lead his North African congregation through these trials and doubts.

In his life before Christ, Augustine had a mistress, was in a cult, and enjoyed academic prestige. He knew firsthand that the world could offer only ephemeral and empty happiness. After his conversion, he devoted his life to showing others that only the knowledge and love of God can satisfy the longing soul.

Augustine offered abiding Christian truths that comforted believers and bolstered their faith in the midst of diminished cultural and political influence. In his authoritative work, The City of God, Augustine defended the supremacy of Christianity and reminded believers that their most important citizenship lies in a kingdom that is not made with hands.

"Two loves," Augustine writes, "have made two cities." The "love of self, even to the point of contempt for God, made the earthly city, and love of God … made the heavenly city." The city of man "seeks its glories in itself," but the city of God "glories in the Lord" (XIV. 28).

Augustine recognized that these cities often overlap; believers must live in both. As a result, Christians are bound to experience the consequences of sin and selfishness that govern the earthly city. In order to avoid despair and to promote goodness in the earthly city, the church must hold fast to their identity and mission as citizens of the eternal city. Motivated and filled with God's truth and love, pastors advance human flourishing and social "unity and concord" by pointing their congregations and neighbors to their common Creator and his good will for humanity (XII. 28).

Although suffering and exclusion is painful, it is only temporal; no loss of earthly fortune can take away the church's virtue and happiness in God. Earthly affliction tests where our love ultimately lies, driving us to cherish God as greater than the fleeting pleasures of this life.

When Christianity has a period of cultural prominence, it's easier to esteem the social benefits of being a Christian above the eternal ones. Following Augustine's example, pastors have a vital opportunity to direct their people to rest their ultimate hope in God, not earthly kingdoms.

The Family in Decline

"There has never been a time when the family faced so severe a crisis as the time in which we are now living." This quote could have come in the wake of the Supreme Court's legalization of same-sex marriage, or in response to the rising rates of fatherlessness and divorce and abortion in recent days. Actually, the statement was made over a century ago by the Dutch pastor-theologian Herman Bavinck (1854-1921).

In 1908, Bavinck published The Christian Family in response to "the worship and the denigration of the woman, tyranny as well as slavery, the seduction and the hatred of men, both idolizing and killing children; sexual immorality, human trafficking, concubinage, bigamy, polygamy, polyandry, adultery, divorce, incest; unnatural sins whereby men commit scandalous acts with men, women with women … glorifying nudity."

Feeling dizzy? Bavinck's social context witnessed the dramatic consequences of the French Revolution on European sexual standards. Armed with the rhetoric of liberty, many promoted the legalization of prostitution as well as "open marriage and free love." New developments in evolutionary theory led some scientists to reduce the family to naturalistic explanations and social functions.

While saddened by the condition of the family in his time, Bavinck didn't retreat or lose hope. Bavinck focused on personal reform: "All good, enduring reformation … takes its starting point in one's own heart and life." Whoever seeks "deliverance from the state must travel the lengthy route of … referendums, parliamentary debates, and civil legislation, and it is still unknown whether with all that activity he will achieve any success."

Following Bavinck, pastors today can promote reform, hope, healing, and growth for families in their congregations. When the church is confronted with societal pressures, it's easy to attack impersonal evil forces "out there," forgetting that family issues are daily realities for the people in the pews.

Bavinck's use of Scripture in his preaching and counsel shows how Scripture's grand story from Genesis to Revelation unfolds God's design and deliverance for families.

First, Bavinck stressed the reason God created the family in the first place: to reflect the relational dynamic within the Trinity, a fellowship, each member complementing the others to fulfill its unified mission. Since the family is likewise a "full and complete fellowship," the purpose of husband and wife is to mirror the goodness, covenantal devotion, beauty, and sacrificial love of the Trinity by serving, honoring, and savoring the other. In wedding ceremonies and marital counseling, church leaders can actively promote thriving, God-honoring marriages by urging spouses to enjoy each other, seek the other's welfare, and cooperate in mutual goals.

Rather than blaming social evils for the failure of families to live up to that purpose, Bavinck helps congregants see how their personal sins of selfishness, lust, greed, pride, disbelief, anger, and hate undermine our best attempts. Guiding a couple through passages like Ephesians 5:22-33, a pastor can lead families to see the sin in their marriage that undermines self-sacrificial love, support, and respect.

The gospel can be powerfully applied to imperfect families. Bavinck shows pastoral sensitivity for the fact that no family will ever completely overcome sin in this life. Thus, we hope in the heavenly reality that the family represents: the union of Christ and his bride, the church, in which God's family will live in perfect fellowship, unity, and love forever. Pastors can demonstrate how faith in Christ's death and resurrection provides reconciliation, not only with our heavenly Father, but with our earthly father, mother, spouse, sibling, and child. The gospel empowers believers to extend to their own families the same forgiveness, grace, sacrifice, and love that God has displayed toward us.

The Kids Aren't Alright

A recent Pew Research Center study on "America's Changing Religious Landscape" confirmed our anxieties: youth are aban-doning Christianity. More millennials identify as "nones," and young adults are increasingly turning away from faith while in college. Fewer wish to associate with institutional forms of religion, finding many churches hypocritical, judgmental, too political, outdated, and culturally isolated. This youthful exodus seems substantial and unprecedented from our limited viewpoint.

In actuality, anyone optimistic about younger generations are the exception, not the norm, throughout history. Pastors through the centuries have worried about the youth carrying the faith forward.

Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758), the Puritan pastor and leading theologian of the Great Awakening, had a deep concern for youth in his day. As he explained in A Faithful Narrative, "licentiousness for some years greatly prevailed among the youth of the town," who engaged in "night-walking, and frequenting the tavern, and lewd practices, wherein some, by their example exceedingly corrupted others." They often met "in conventions of both sexes, for mirth and jollity" late into the night "without regard to any order in the families they belonged to." There was even a nasty controversy over boys passing around pornography. Edwards faced many challenges: youth were indifferent to Christianity, defiant toward their family, and premarital sex and pregnancy was an ever-growing problem in Northampton.

Edwards stressed the importance of not taking youth for granted and using it as an opportunity to take part in God's kingdom. In a sermon titled "The Preciousness of Time," he urges, "Don't let the precious days and years of youth slip without improvement." Edwards challenged those who wished to enjoy the world in their youth and get serious about Christ later in life. He paints youth as an opportunity, not a curse or an excuse. Giving God the first fruits from youth rather than wilted fruit in old age affords greater time for using one's gifts to achieve wonderful things for God's kingdom. Edwards states, "You had need to improve every talent, advantage, and opportunity to your utmost, while time lasts."

Like Edwards, today's pastors can urge youth to invest these important years for Christ. Pastors (and parents) are uniquely positioned to provide opportunities for youth to use and grow their gifts through mission work, meeting the needs of the elderly and needy in your community, and through corporate and private prayer and Scripture reading.

Open their eyes to the vastness of the world and its need for hope and salvation. Help them experience the rewards of serving the needy, and urge them to taste the riches of knowing Christ for themselves. Encourage them to be salt and light, countercultural, unapologetic witnesses of the gospel in their circles of friends.

Young people responded to Edwards' challenge. Their example motivated older believers to take their own faith more seriously. Edwards inspired the younger generation in his time to take initiative in their personal discipleship by challenging them and giving them space and opportunity to grow and flourish.

Ryan Hoselton lives in Heidelberg, Germany, with his wife and daughter. He's currently a doctoral student at Universität Heidelberg.

Copyright © 2015 by the author or Christianity Today/Leadership Journal. Click here for reprint information on Leadership Journal.