In this series

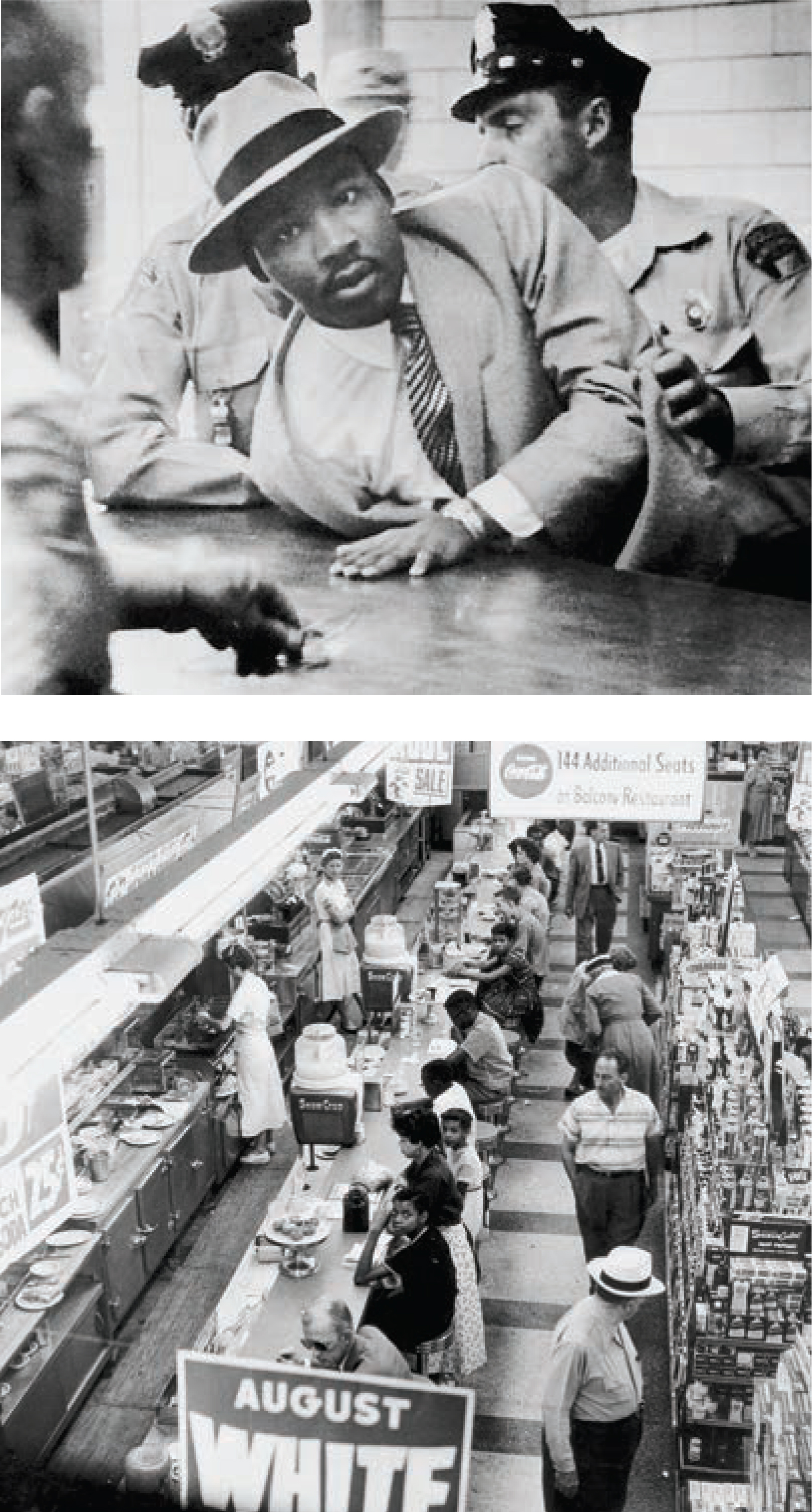

In June 2015, in the wake of Dylann Roof’s murderous rampage at a historic black church in Charleston, South Carolina, legislators gathered to debate removing the Confederate flag from the state capitol. Meanwhile, Bree Newsome, a young African American woman, was taking the matter into her own hands, scaling the flagpole and snatching the flag herself. Though she was promptly arrested, her action attracted media attention, and many hailed it as a victory for racial justice.

Newsome had been arrested two years earlier for protesting North Carolina’s voter ID law. As such, she was anything but reticent about her motives. Ordered by police to come down, she replied, “In the name of Jesus, this flag has to come down. You come against me with hatred and oppression and violence. I come against you in the name of God. This flag comes down today.” As officers handcuffed her and led her away, she recited Psalm 23.

As the Confederate flag controversy died down, another controversy was heating up in rural Rowan County, Kentucky. Another woman of unbending Christian conviction—albeit very different politics—quickly gained notoriety for her own defiant stand. Kim Davis, the county clerk, ceased issuing marriage licenses after the US Supreme Court ruled in favor of same-sex marriage. Davis, a recent convert, framed her refusal as a defense of her religious freedom. Jailed briefly for contempt of court, she continued fighting several legal actions launched against her, styling herself a “soldier for Christ.”

But where Newsome was celebrated for her courage, Davis was mostly scorned as a religious fanatic and a bigot. Although a handful of conservative Christian politicians and activists rallied to her side, the consensus alternated between mockery and outrage.

Davis’s gambit may well have been ill-advised, especially coming from a government official sworn to uphold the law of the land. Certainly, a number of thoughtful Christian commentators have questioned the wisdom of her approach. But taken together, these two episodes reveal a deep-seated ambivalence about civil disobedience—peacefully refusing to obey a law or decree that one believes is unjust, and accepting the consequences (including imprisonment and death). Why are some forms of resistance inspiring, while others leave us feeling uneasy?

Blaming bias against conservative Christian culture-warring only goes so far. After all, most people instinctively realize that society can’t function if everyone feels free to ignore laws they oppose. Replacing the rule of law with the rule of private conscience is a recipe for anarchy.

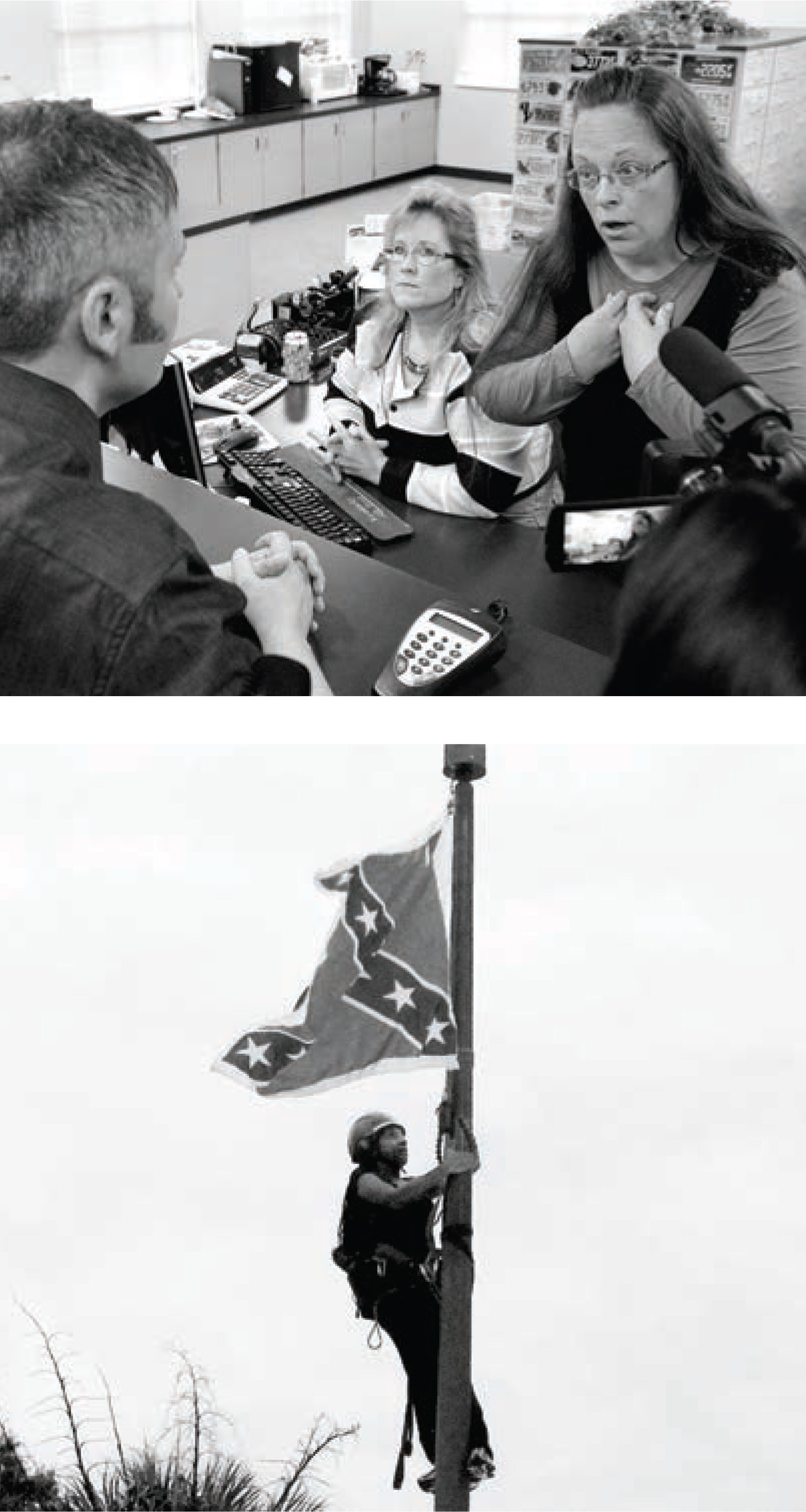

Recent history is another important factor. Americans are not so far removed, generationally, from the civil rights movement, which made lunch-counter sit-ins and other forms of civil disobedience a strategic centerpiece. Although the movement and its methods were viciously opposed at the time, today they bask in near-universal reverence. Understandably, acts of civil disobedience that strike blows against racism and the legacy of segregation—like tearing down a Confederate flag—win easy applause. But acts that don’t map so neatly onto the civil-rights playbook—like standing athwart the same-sex marriage revolution—seem suspicious if not dangerously radical.

No one who confesses that Jesus Christ is Lord can meekly submit to the proposition that man-made laws are sacred and inviolable.

For Christians in peaceful, tolerant, modern America, even broaching the subject of civil disobedience can seem wildly inappropriate. Among secular hardliners, the phrase often carries a distinct whiff of paranoia. Even among believers, complaining about Caesar’s heavy yoke can look like an affront to victims of genuine persecution—the violent kind meted out by ISIS fighters. It all adds up to a strong presumption that unless there’s a clear family resemblance to the civil rights movement, civil disobedience is simply beyond the pale.

But given the trend lines of our culture, it’s time to rethink this presumption. Christians face intensifying pressure to compromise their convictions and conform to secular ideologies. Calculated lawbreaking won’t be the right response to every government provocation, and it should never be undertaken lightly—especially in democratic societies where offensive laws can be debated, protested, and changed. But no one who confesses that Jesus Christ is Lord can meekly submit to the proposition that man-made laws are sacred and inviolable. We need to restore a bold willingness to treat principled resistance as a live possibility, rather than a relic of a bygone era.

Butting Heads with the Powers-That-Be

What happens when the demands of government contradict our faith in a fundamental way? What if, like Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, we are called to bow the knee to a false god and, in so doing, deny the one true God (Dan. 3)? Or, more likely, what if we are made to bow before more subtle idols of material success, sexual freedom, or national glory? Or called to fight in an unjust war?

In parts of the Middle East and South Asia, ancient Christian communities face the threat of extinction. Demands to forsake their faith are overt and unrelenting. In such contexts, civil disobedience is not an intellectual exercise. It’s the only available path.

But in North America and the English-speaking world, the situation is considerably less precarious. Government agents do not sit in our churches, as in Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, assessing the ideological correctness of everything said from the pulpit. Instead, we’re accustomed to thanking God that we are free to worship without fearing for our lives or livelihoods. The prospect of civil disobedience seems mercifully remote.

Nevertheless, as long as we follow Scripture in living under God’s all-encompassing sovereignty, we’re bound to butt heads with the powers-that-be on occasion. The legal and cultural triumph of same-sex marriage has accelerated one such clash, pitting dissenters from the new orthodoxy against non-discrimination laws and local human rights commissions. Witness the wave of fines imposed on bakers, florists, and photographers who decline to lend their talents for same-sex weddings.

Another major source of tension is the Obama administration’s Affordable Care Act, which puts many faith-based organizations between a rock and a hard place. Under a regulatory mandate issued by the Department of Health and Human Services, these organizations must offer (or facilitate) employee insurance plans that cover contraceptives, including what many believe to be abortifacients. Churches themselves are exempt from the mandate, but faith-based schools, charities, hospitals, and businesses must comply. Institutions as diverse as Wheaton College, the University of Notre Dame, Hobby Lobby, and the Little Sisters of the Poor have sued to protect their religiously rooted policies.

That litigation is ongoing, its ultimate outcome still up in the air. (Last month, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the Little Sisters case.) The Obama administration continues to insist that an employee’s right to certain health benefits outweighs a religious employer’s objections. What happens if the courts ratify that stance?

Official secularism is at least as aggressive in my adopted country of Canada. In 2007, Quebec’s provincial education ministry adopted a religious studies curriculum and mandated its use in all schools, even private faith-based schools. The stated purpose was “to help students develop a spirit of openness and discernment with regard to the phenomenon of religion and to enable students to acquire the ability to act and to evolve intelligently and with maturity in a society that reflects a diversity of beliefs.” Schools were expected to teach the course from a neutral standpoint. Loyola High School, an English-speaking Catholic school in Montreal, protested this infringement on its confessional identity.

The dispute went all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada, which ruled in 2015. The court sided with Loyola, but only narrowly—and without upholding a vigorous understanding of religious freedom. Writing for the majority, Madam Justice Rosalie Abella concluded: “To ask a religious school’s teachers to discuss other religions and their ethical beliefs as objectively as possible does not seriously harm the values underlying religious freedom.” In short, a Catholic school must pretend not to be fully Catholic when teaching about other religions.

Before we’re tempted to imagine that it’s mainly “conservative” causes at risk from government overreach, consider churches that reach out to immigrants, without regard to their legal status. Restrictive immigration laws sometimes contain provisions that place their activities on uncertain legal footing. In 2011, Alabama passed a law (most of which the courts later overturned) against harboring or transporting unauthorized immigrants. A free-exercise complaint brought by Episcopal, Methodist, and Roman Catholic bishops said the law would “make it a crime to follow God’s command to be Good Samaritans.”

Likewise, faith-based efforts in Texas to resettle Syrian refugees are in legal limbo following a November 15 letter from the state’s Health and Human Services commissioner ordering volunteer groups to “discontinue those plans immediately.” Texas Impact, a grassroots interfaith network, quickly issued a statement decrying “pressure [on] faith-based organizations to violate the sincerely held beliefs of their religious traditions.” As executive director Bee Moorhead noted, “It would be difficult for Christians to think of themselves as Christian without welcoming the stranger.”

So what do we have here? The ordinary push and pull of competing forces in a democratic society? Or something closer to stark choices between obedience to man and fidelity to Christ? In ideal circumstances, “good Christian” and “good citizen” aren’t mutually exclusive categories. Yet in any earthly community, we are but “foreigners and exiles” called to “live as God’s slaves” (1 Pet. 2:11, 16). How do we know when the duty to resist eclipses the duty to obey?

Fortunately, God’s people have confronted this question for more than three millennia—and not just in the abstract.

Early Church Resistance

Under most circumstances, the Bible urges obedience to government. Those in political power are charged with securing justice, caring for the common good, punishing crime, and settling disputes. In Romans 13, Paul tells his readers: “Let everyone be subject to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which God has established. The authorities that exist have been established by God” (v. 1). Peter similarly urges his followers: “Submit yourselves for the Lord’s sake to every human authority: whether to the emperor, as the supreme authority, or to governors, who are sent by him to punish those who do wrong and to commend those who do right. . . . [F]ear God, honor the emperor” (1 Pet. 2:13–14, 17).

Yet on two occasions in Acts, when the apostles were expressly prohibited from proclaiming the gospel, they answered without hesitation: obedience to God trumps all human authorities (4:19; 5:29). The earliest believers knew where to draw a clear line: no ruler would forbid them from worshiping God, much less compel them to worship a counterfeit. Like Daniel’s Hebrew friends in Babylon (not to mention Daniel himself), they would sooner die than compromise their loyalty to God.

Indeed, many early Christians—including nearly all of the original apostles—met untimely deaths for preaching the gospel. The imperial cult of Rome, in particular, unleashed several waves of persecution. Under its terms, the empire’s diverse subjects were allowed to worship according to their own traditions. But they were also expected to burn incense to the emperor as to a god. Roman authorities thought this eminently reasonable and tolerant. They weren’t seeking a bland religious uniformity, just looking to shore up loyalty to their rule. Who could object?

Following God’s explicit will forced a confrontation with the Roman authorities, even if that meant courting certain death.

In this context, that Jews and Christians insisted on worshiping the one true God appeared needlessly exclusive. But the second commandment was clear: “You shall not make for yourself an image in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below. You shall not bow down to them or worship them; for I, the Lord your God, am a jealous God . . .” (Ex. 20:3–5). Following God’s explicit will forced a confrontation with the Roman authorities, even if that meant courting certain death.

Of course, there was nothing wrong with following Rome’s legitimate decrees. Jesus had said so himself. When the Pharisees tried goading him into speaking against imperial taxes, he surprised them with words that form the touchstone of Christian reflection on civil disobedience: “Give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s” (Mark 12:17). Some mistakenly interpret this to mean that there are two kingdoms—one belonging to God and the other to Caesar. But that would put God and Caesar on the same level. In reality, Caesar receives his authority, including his divine mandate to rule, from God. As Jesus affirmed before Pontius Pilate: “You would have no power over me if it were not given to you from above” (John 19:11).

The Reformation forced Christians to reflect once again on the limits of Caesar’s domain. In previous centuries, when Western Europe was essentially a single Christian commonwealth, occasional clashes between political and church authorities rarely spilled over into the pews. But by the 16th century, the Reformers would face hostility from both pope and emperor.

Martin Luther may or may not have uttered his famously defiant declaration—“Here I stand. I can do no other”—before the Holy Roman Emperor. But he was certainly skeptical of civil disobedience. Condemning a German peasant uprising, Luther cited Romans 13 and 1 Peter 2, justifying disobedience only when government tries to coerce faith.

Like Luther, John Calvin supported obedience to political authority, which he praised in the highest terms: “Its function among men is no less than that of bread, water, sun, and air; indeed, its place of honor is far more excellent.” He held that Scripture requires obedience even to a bad king, who may be carrying out God’s judgment. Calvin favored constitutional checks on the ruler’s authority, but he opposed individuals launching rebellions.

Two major 20th-century events decisively shaped the church’s perspective on civil disobedience: the rise of Nazi totalitarianism in Germany and the struggle for black civil rights in the United States.

In 1934, one year after Hitler’s rise to power, a group of church leaders gathered to condemn the so-called “German Christians” for cozying up to the Nazi regime. Largely written by Swiss theologian Karl Barth, the resulting Barmen Declaration took a stand against exalting “other lords” or “changes in prevailing ideological and political convictions” above the Word of God. While Barmen did not directly challenge the Third Reich, it laid theological foundations for resisting Hitler’s decrees. In the Netherlands, for example, many Reformed Christians, heirs of the great Dutch theologian and statesman Abraham Kuyper, secretly sheltered Jews in their homes.

Picking up on the themes of the Barmen Declaration, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, in The Cost of Discipleship, follows Luther and Calvin, affirming the stance of Paul and Peter on obeying the governing authorities. During World War II, however, he became a heroic resister, using his German intelligence position to help subvert Hitler’s efforts and eventually becoming implicated in a 1944 assassination plot.

Nearly two decades later, Martin Luther King Jr. found himself in jail after launching a nonviolent campaign against segregation in Birmingham, Alabama. While there, he penned one of history’s most eloquent defenses of civil disobedience, his Letter from a Birmingham Jail. How, opponents asked, could King justify breaking state laws while at the same time urging state governments to respect the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. The Board of Education? King responded by appealing to both Augustine and Aquinas: “An unjust law,” he argued, “is no law at all.” A law “that uplifts human personality is just,” while one “that degrades human personality is unjust.”

For King, proper civil disobedience upholds, rather than undermines, the rule of law: “I submit that an individual who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust, and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law.”

Okay to Disobey?

Most believers today would support King’s vision of civil disobedience, at least as it applied to the glaring injustice of state-enforced segregation. But how should we determine whether, or when, civil disobedience is warranted in our own day, when conflicts between government action and Christian conviction aren’t always clear-cut?

Obviously, deliberate lawbreaking should never be undertaken casually. Christians have always understood that public justice depends on the rule of law. We need prudent laws to coordinate shared undertakings, protect common goods (such as public safety), and ensure fair treatment for individuals and communities. When, then, might the moral threshold for civil disobedience be met? Beyond explicit commands to deny God or worship false gods, it might be impossible to define a standard that holds true in every case. But here are some guidelines to remember, no matter the situation:

1. The Christian life is not simply a matter of subjective religious experience; it is a way of obedience to the revealed will of God in Christ.

Too often, out of a false humility, Christians settle for a defensive posture. Wanting to appear “tolerant” to the larger society, we shrink back from boldly proclaiming Christ’s sovereignty over all of life. Certainly, we ought not to place unnecessary barriers between the church and the surrounding society. But the church’s call to obedience does not hinge on that society’s sympathy or permission.

2. Political leaders owe their authority to God, whether or not they acknowledge it.

In biblical times, kings and princes fancied themselves gods, a reality reflected in such passages as Psalms 58 and 82. God is sometimes described as “the great King above all gods” (Ps. 95:3), indicating his sovereignty over pretenders to his throne. The psalmist affirms: “Rise up, O God, judge the earth, for all the nations are your inheritance” (Ps. 82:8). If God is King, then our laws must conform, in at least some limited way, to his standards of righteousness.

We need not support theocracy to recognize that the Bible calls on earthly rulers to do justice within the context of their offices (Ps. 82, Isa. 10:1–2). Christians as far apart politically as Jim Wallis and James Dobson have recognized this. To remain faithful to our calling, we cannot keep our light hidden under a bushel (Matt. 5:15). When rulers ignore or flagrantly transgress their biblical mandate, believers may need to take dramatic steps to awaken consciences and agitate for change.

3. Even an unjust law does not invalidate the entire political order.

A few years before the Civil War, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison burned a copy of the Constitution, calling it “a covenant with death” and “an agreement with hell” for its toleration of slavery. A century later, King would appeal to the same Constitution. Garrison’s stance contributed to the outbreak of war, while King’s approach helped secure civil rights for African Americans by the mid-1960s. The lesson? Where a political system can accommodate reform movements, it’s generally best to renounce revolution and work for justice within the system.

4. Contemplating civil disobedience is best done in community.

Human beings are never autonomous. We always answer to another, whether to God or a human institution of some sort. Rightful civil disobedience cannot rest on self-assertion—the sacred, conscience-driven Me asserting independence from the law. We break the bonds of civil authority only because we belong primarily to a higher authority—to God and his church.

There is not only strength in numbers, but wisdom as well. If my fellow Christians agree that a ruler is mandating something idolatrous or unjust, this strengthens my conviction. But if they disagree, I’m bound to ask whether my judgment is mistaken.

5. The means of civil disobedience matter as much as the ends.

During World War II, European resisters engaged in illegal and sometimes violent acts against their German occupiers. Subsequent generations have judged them heroic because they battled an obvious evil. Pro-life activists deem our permissive abortion laws every bit as monstrous. Yet the vast majority forswear violence, because they understand that even a worthy end cannot justify immoral or disproportionate means.

You don’t cure a bunion by amputating the foot. If we choose the path of civil disobedience, it must be tailored to the circumstances. Not every injustice amounts to genocide. Not every objectionable law or court decision constitutes an emergency. Telling the difference requires much wisdom and prayerful discernment.

6. Finally, as Dr. King readily acknowledged, anyone engaging in civil disobedience must be prepared to suffer the consequences.

King went to jail more than once. British authorities repeatedly arrested Gandhi, hoping to stifle his movement for Indian independence. Perhaps the day will arrive when Christians in “free” societies are imprisoned for refusing to affirm certain tenets of secular morality. Scary though this prospect may seem, it is part of our witness to the gospel.

In the meantime, we’re still called to reflect God’s grace in a sinful, hurting world. Where we can change laws and constitutions, let’s make every effort to do so. But it’s no secret that Christian convictions run seriously afoul of the spirit of the age. Caesar’s edicts may create situations where living them out puts us on the wrong side of the law.

Civil disobedience is our very last resort, to be contemplated only with fear and trembling. But by no means can faithful believers rule it out of bounds.

David Koyzis is the author of Political Visions and Illusions (IVP Academic) and We Answer to Another: Authority, Office, and the Image of God (Pickwick). He teaches political science at Redeemer University College in Ontario.