One morning this past September, Gene Luen Yang was backing out of his driveway in San Jose, California, to go to his writing studio—a nearby Panera Bread—when he got a call. Someone from the MacArthur Foundation was on the other end, informing him that he was among 23 winners of the $625,000 MacArthur Fellowship. Also known as “genius grants” (a term the foundation dislikes), the annual award recognizes innovative, creative leaders in any industry who are American citizens or residents.

“I eventually made it to Panera,” the Chinese American graphic novelist, writer, and cartoonist told Vulture. “But I didn’t get much work done.”

A MacArthur Foundation statement said that Yang was recognized for “bringing diverse people and cultures to children’s and young adult literature and confirming comics’ place as an important and creative force within literature, art, and education.”

As our news sources, social media feeds, and even our churches are increasingly siloed, many Christians feel disconnected from their neighbors and the world. Yang’s work counteracts this trend, nudging us to explore the different and the unfamiliar to better understand—and love—perspectives that are not our own.

Yang is among a distinguished slate of Americans who have been awarded the no-strings-attached prize, including paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, activist Marian Wright Edelman, sociologist William Julius Wilson, and writers George Saunders and Ta-Nehisi Coates. Yang, 43, is only the third graphic novelist to receive the honor in its 35-year history.

“I don’t know if it will ever actually sink in,” Yang admitted to me in an interview two weeks after the announcement. “It feels really crazy. It’s beyond anything I could have expected for my life.”

According to Mark Siegel, his longtime editor at First Second Books, such an unassuming response is classic Gene Yang. “I’ve never seen anything go to his head. I’ve never seen him take anything for granted. If anything, it makes him work harder.”

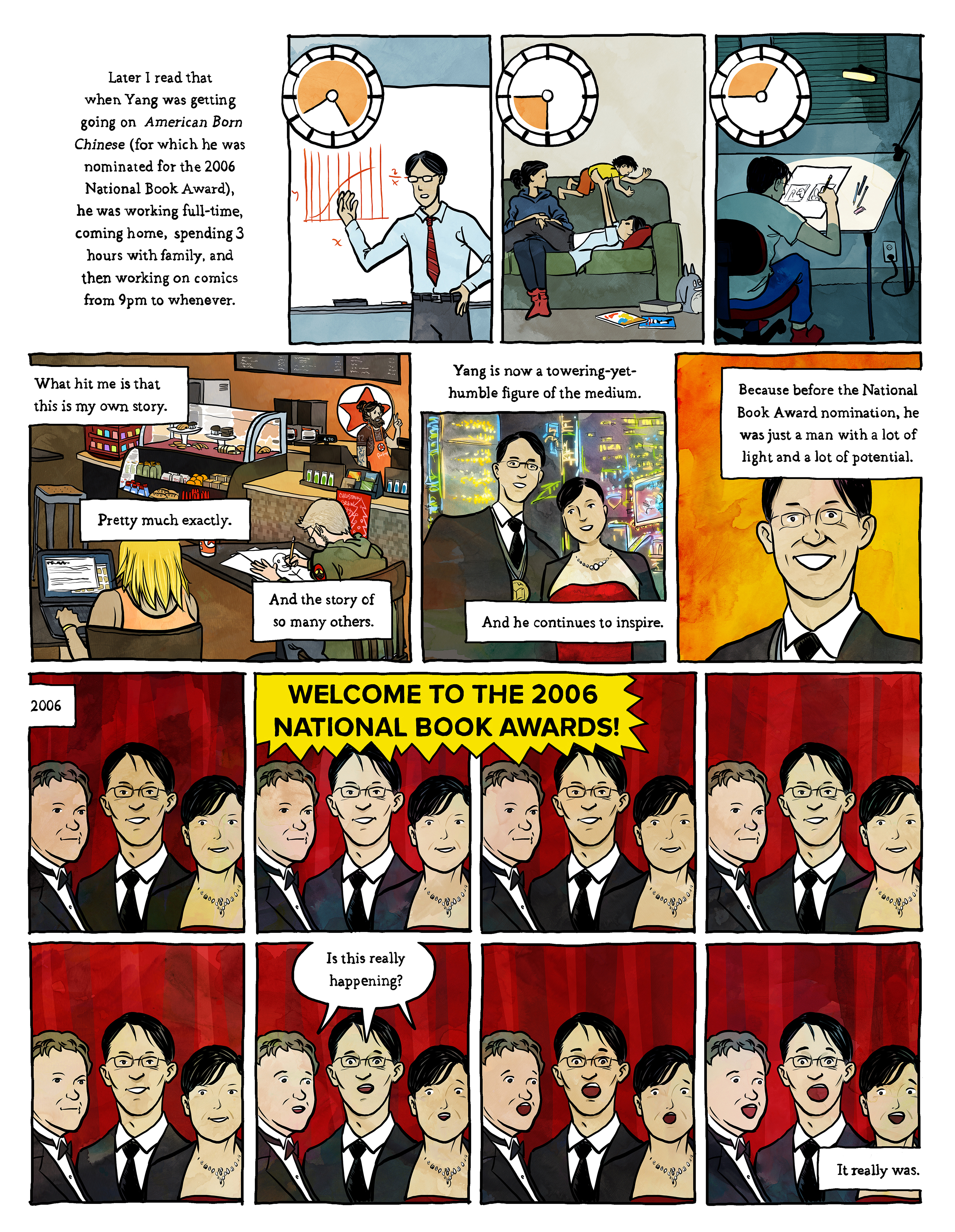

Siegel would know better than anyone. “When I first signed up Gene, he was pretty much photocopying and stapling his mini comics and losing money on them at Comic-Con,” Siegel said. “And then 18 months later we were in Times Square at the National Book Awards in our tuxedos. We were looking at each other, going, ‘Did something just happen?’ ”

A remarkable number of things have happened since Yang’s breakout graphic novel, American Born Chinese, was published in 2006. It was the first book in its genre ever to be named a National Book Award finalist and to win the Michael L. Printz Award for Excellence in Young Adult Literature. His next major solo graphic novel, the two-volume Boxers & Saints (First Second, 2013), also won a raft of awards. Yang has collaborated with other artists on award-winning stories and graphic novels and has written for the popular Avatar: The Last Airbender and Superman comic book series. In 2016, he was named an Ambassador for Young People’s Literature by the US Library of Congress and made his debut as the writer of DC Comics’s New Super-Man comic series, whose hero is a Chinese man living in modern Shanghai.

Despite Yang’s impressive resume, every individual I interviewed started with something like: “He is one of my favorite people,” or “He is one of the best human beings I know,” or simply “I love Gene!” They are fans not just of his work, but of the man himself.

Christian author Matt Mikalatos, who has known Yang for several years, told CT, “He’s humble, kind and generous to people around him. He’s a lot like his work: deep, intelligent, thoughtful, but also full of life and funny.” Jason Jensen, a longtime friend and mentor, called Yang a “goofball. Gene is a person of lighthearted joy, mixed with deep, thoughtful faith.”

Living In Tension

The person of Gene Luen Yang—a modest, lovable goofball—seems incongruent with the artist who explores weighty topics like ethnic identity, racism, and religious fundamentalism in his stories. But Yang has always been a person of contradictions, caught in between different worlds.

This “tension,” as Yang calls it, is probably the greatest force shaping his art, his identity as a follower of Jesus, and the growing impact of his work, which extends far beyond the Asian American community.

Yang’s father is a Christian engineer from Taiwan. His mother, a programmer from Taiwan and Hong Kong, converted to Catholicism after immigrating to the United States. Yang grew up attending a Chinese Catholic Church in the San Francisco Bay Area.

At school, Yang was one of a few Asian students and was regularly mocked by his classmates. His faith also made him an outsider, as some aspects of Christianity have been viewed by some as incompatible with Eastern traditions. And even among Chinese American Christians, who lean heavily Protestant (over two-thirds according to a 2012 Pew Research study), Yang is an anomaly as a Catholic.

Despite Yang’s impressive resume, every individual I interviewed said some version of “He is one of my favorite people.” They are fans not just of his work but of the man himself.

Yang wanted to pursue art and animation since childhood; his parents preferred that he become a doctor, lawyer, or engineer. As Yang was preparing to attend college, his father insisted, “Do something practical. After graduation, I’ll leave you alone.” (They ended up compromising: Yang majored in computer science and minored in creative writing.)

While a student at the University of California–Berkeley, Yang found himself in a majority Asian American population for the first time in his life. “I think that was when I started being able to explain and understand the discomfort I had had since I was a kid,” he said in a 2013 interview.

Even as Yang came to a deeper understanding of his ethnic identity, he entered a period of serious doubt about his faith. These two processes were very much related, Yang told me. “So much of college is about figuring out where you fit in the world, who you are, how you’re going to build your identity. Faith and culture both play into that. They overlap.”

He found a spiritual home in UC Berkeley’s InterVarsity Christian Fellowship chapter. “That was the first time I saw people my age actually live out a metaphysical reality. I saw people treat church and faith seriously,” said Yang. But the tensions remained. “I remember most of the people around me were Protestant, and there were a handful of Catholics. We would get together from time to time to talk about things. It pushed me to think and to wrestle a little bit more.”

Exploring Empathy

Yang admits these tensions were not always easy for him to navigate, but his perspective on not fitting in has changed over time. “Now, when I look back, I feel really grateful and appreciative of being an outsider,” Yang told me. “When you are in a place of comfort, there are things you end up taking for granted.” While his upbringing and education were privileged in many ways, Yang is familiar with the feeling of cultural discomfort.

Spurred on by the complex tensions between his Chinese-Christian and Western-American heritage, Yang’s work represents an ongoing quest to better understand himself, his faith, and the world around him. He often takes his characters on similar journeys of exploring identity, place, and purpose—something that readers of any cultural and faith background can connect with.

“There are universal themes that jump out from his stories that a lot of people can relate to,” explained Phil Yu, a leading advocate for Asian American representation in arts and media, and founder of the Angry Asian Man blog. “He writes with such empathy. His stories have such a sense of humanness that really speaks to us. And he delivers it in such an entertaining, approachable way.”

Take Yang’s breakout graphic novel, American Born Chinese, which explores identity and self-acceptance. The story centers on a Chinese American boy struggling to fit in at school, who goes so far as to imagine himself as a blond Caucasian. Though the narrative details are specific to the Asian American experience and speak particularly to those readers, American Born Chinese has been embraced across American society and has become a literary staple in classrooms nationwide.

“Gene’s characters are always people in two worlds,” Mikalatos said. “They’re navigating the differences between themselves and the conflicting worlds around them. Those people tend to be able to see people as individuals and, once they embrace their own identity, to be able to reach out and help others.”

This empathy is best exemplified by Yang’s Boxers & Saints, which explores the 1900 Boxer Rebellion in China from two distinct and equally sympathetic perspectives: a young Chinese girl, rejected by her own family, who is taken in by Christian missionaries and converts; and a young leader of ragtag peasants determined not to let Western colonialism destroy Chinese traditions.

When he was researching for Boxers & Saints, Yang was desperately looking for one central protagonist. “I wanted a hero, but I couldn’t find one that was complete. I felt like there were heroes on both sides.”

This is a surprising statement, given the complex and violent history of the Boxer Rebellion. The violent, anti-foreign, anti-Christian uprising occurred between 1899 and 1901, precipitated by oppressive colonial rule. In addition to a long siege against Beijing (then called Peking), Boxers murdered some 32,000 Chinese Christians, many of them children. A coalition of Western armies eventually quelled the rebellion, in turn plundering the capital and countryside, and summarily executing suspected Boxers.

For Yang, though, the point of Boxers & Saints is not who won or who was most at fault. Instead, it’s about how the Christian missionaries and the Boxers both wanted to protect Chinese culture—their motives were the same, even if their methods were vastly different.

This illustrates another unique facet of Yang’s work: He explores cross-cultural stories from a perspective of faith, allowing for ambiguity and for questions to remain unanswered. “Christian-themed fiction for kids and teens can sometimes feel like after-school specials,” blogger Grace Hwang Lynch told CT. Lynch frequently writes about Asian American culture and mixed-race identity. “The protagonists are usually white and there’s a clear-cut moral at the end. Yang’s stories often don’t have happy or tidy endings.”

“Now, when I look back, I feel really grateful and appreciative of being of being an outsider.”

For Yang, this complexity is perfectly consistent with his Christian faith. “The older I get, the more value I find in tension,” he explained. “That’s reflected in my faith, in the person of Christ. It only makes sense in tension. Jesus is both man and God. The last shall be first.” Rather than something to be feared, these paradoxes have catalyzed deeper growth in Yang’s faith and character—as well as the narratives he tells.

Yang seamlessly integrates his faith into his graphic novels and comics through biblical allusions, Christ or Christ-like figures, and story arcs that bend toward grace and redemption. And yet it’s his reflection of the world as we experience it—with more questions than answers, with multiple sides to the same story, with people who are capable of good and evil—that makes his work so compelling to Christians and non-Christians alike.

This broad appeal is intentional on Yang’s part, whose team of editors and beta readers includes atheists. “I think that even regardless of whether you consider yourself religious or not, there is always a search for meaning. How you arrive at that meaning depends pretty heavily on how you answer certain metaphysical questions.”

Yang’s humorous, thoughtful, and empathic exploration of our shared struggles as humans is particularly poignant in a time often characterized by deep political and social divides.

When I ask Yang about the current political climate in the United States, his response goes even further than empathy. He argues that we need people who are different from us. “I believe that if you have two poles, if they’re both healthy, the tension between them ought to lead somewhere good. If we play different roles, even if it seems like we’re in opposition to one another, ultimately what comes out is good.”

We needn’t worry that he’ll lose that sense of tension anytime soon. When I asked Yang how his parents responded to his winning the MacArthur Fellowship, he says they were really happy for him. A few days later, though, his father texted him these words: “I don’t regret making you major in something technical.”

“That was it. That was the whole thing,” Yang said, laughing.

Dorcas Cheng-Tozun is a writer and editor who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. Her book on how to survive marriage to an entrepreneur, Start, Love, Repeat, is forthcoming from Hachette Center Street later this year.