Being a black leader in the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) today can be exciting, as America’s largest Protestant denomination makes unprecedented progress toward diversity. But it can also be discouraging. Even small instances of culture clash are hard to overlook when you’re in the minority.

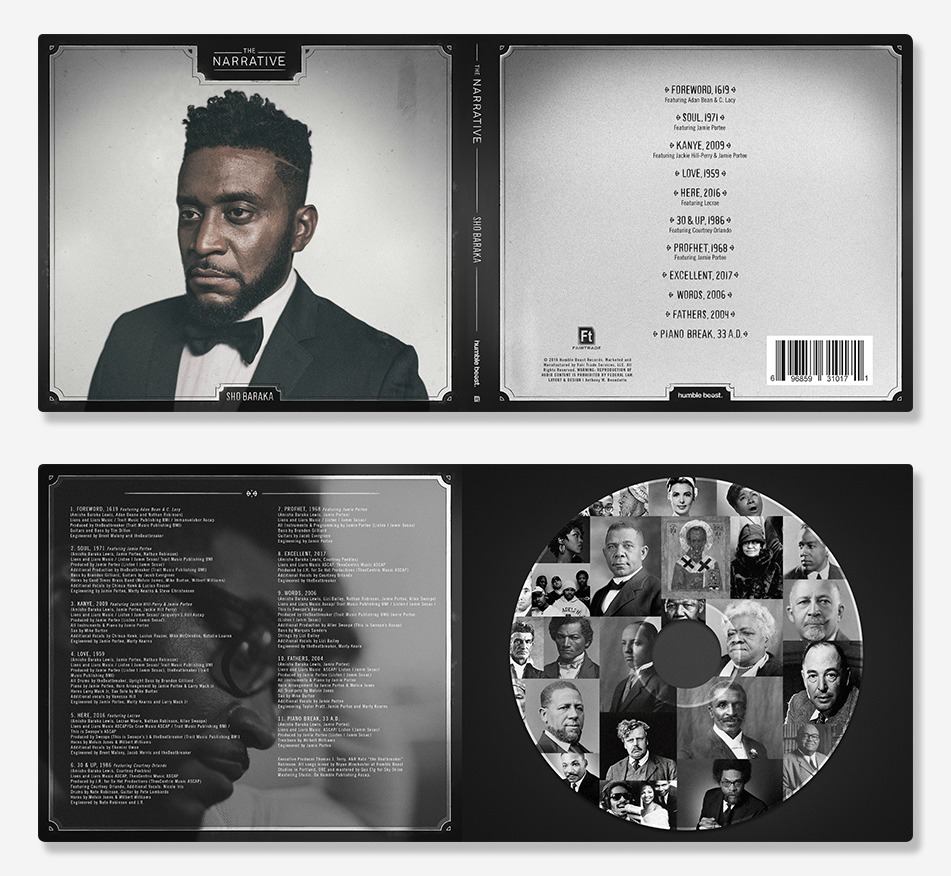

The latest discussion over racial disconnect in the denomination stems from LifeWay Christian Resources’ decision to stop carrying a CD by rapper Sho Baraka at its 170 bookstores. The Washington Post broke the news last week, attributing the decision to a lyric in one track on The Narrative that contains the word penis, though LifeWay’s statement on the matter only referenced inappropriate language.

The SBC’s “strides towards reconciliation and celebration of diversity have been significant,” said church planter Muche Ukegbu. “[They] are more than just talking points to placate the culture.” His congregation, The Brook Miami, is among the more than half of new Southern Baptist church plants—and 20 percent of SBC congregations overall—with mostly non-white members.

“With that being said, it’s situations and instances like this [that are a] frustrating reminder of how out of touch some institutions and leadership really are, and how far we still have to go,” Ukegbu told CT.

For Baraka’s friends and fans, there’s a bigger backdrop beyond one word, one line, or even one album. It’s hard to separate the content of the artist-activist’s recent release from his racial and political identities.

Leading up to the election, Baraka went on tour with fellow Humble Beast artist Propaganda to hold conversations on race and politics at churches in a half-dozen major cities; the 38-year-old also is involved with the Atlanta-based AND Campaign, a movement to rethink political and community engagement.

Baraka wrote for CT about urban Christians’ dilemma in a two-party system. He wasn’t alone in speaking against that tension; Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission (ERLC) president Russell Moore has also had to face fallout for his political remarks critiquing now-President Donald Trump.

Atlanta pastor John Onwuchekwa said for black leaders who represent the changing makeup of the SBC, incidents like Baraka’s CD getting pulled from LifeWay’s shelves feel “like a slap in the face.”

“The last thing I can do is speak authoritatively on motive,” said Onwuchekwa, lead pastor of Cornerstone Church. “In another sense, it felt like more than a penis thing. If this were any other artist, there would have been more credence given.”

Unlike previous cases when LifeWay has pulled materials, Baraka has direct ties to its denomination. The rapper served for years as an elder at Blueprint Church in Atlanta, an affiliate of the SBC’s North American Mission Board. He is scheduled to perform at a Southern Baptist Theological Seminary conference next month. He also shares the denomination’s theological positions on sex and marriage—his reference condemns his own past behavior in light of the gospel.

As Thabiti Anyabwile, the Baptist pastor of Anacostia River Church in Washington, tweeted, “The censorship of a pro-sanctification [message] is the more troubling issue” about LifeWay’s decision.

Not all black Southern Baptist leaders saw LifeWay’s decision through a racial lens. Kevin Smith, executive director of the Baptist Convention of Maryland/Delaware, wrote in an email to CT, “I did not take the LifeWay story to be about race/black culture,” but about the difference in expectations between LifeWay’s consumer base and Baraka’s fans. “Basic appealing to your market 101,” he said.

In 2012, LifeWay pulled The Blind Side from shelves after complaints over the film’s profanity and use of a racial slur. Spokeswoman Carol Pipes declined to comment further on the recent decision or its denominational implications, only saying, “Like any retailer, LifeWay has a responsibility not to carry resources with content our customers consider inappropriate. After receiving complaints about some language in The Narrative CD, LifeWay decided to no longer carry it.”

The chain offers about 20 albums labeled Christian hip-hop/rap, including several by Lecrae and Trip Lee.

After watching his timeline fill with penis references and jokes in reaction to the news, Baraka admitted he was surprised his album was sold at a Christian bookstore to begin with. “There’s a reason we don’t target the soccer mom audience—because of this very issue,” he said in a five-minute video response.

But the rapper understands fans’ disappointment over the news just the same.

“If we’re consistently entrusting our talent, our content, our resources to people who don’t understand us, and we’re frustrated by that, then maybe we need to build our own institutions and networks, or partner with people who do get us and understand the consumers whom we’re trying to reach and serve,” said Baraka, founder of his own outlet, Forth District.

The sense that people “don’t get us” extends down to many of the thousands of Southern Baptist churches where black Christians worship on Sundays. Miami pastor Ukegbu worries that racial minorities who feel misunderstood by leaders and institutions will respond to the situation between LifeWay and Baraka by turning away and hardening their hearts further.

“In the last week since LifeWay pulled The Narrative, I've had to wrestle with a few people in particular in our community on why this shouldn't be the thing that pushes them out the door,” he said.

Onwuchekwa has experienced similar discussions over the years in Atlanta. “As someone who’s black and in cooperation with the SBC, I’ve had to sit down and have conversation with the people prepared to leave” over denominational baggage, he said. “It comes with an explanation.”

The LifeWay decision came in the midst of Black History Month, and days before the SBC’s Racial Reconciliation Sunday. As Baptist News Global reported: “Added to the denominational calendar as Race Relations Sunday in 1965, the observance originally celebrated relationships between black and white Baptist denominations but was renamed as the historically white SBC grew more ethnically and racially diverse.”

Being in a majority-white denomination reflects some of the same ongoing tensions of being in a majority-white culture. “In certain evangelical contexts, it’s not enough for black or brown evangelicals to be conservative Christians or Reformed,” wrote Jarvis Williams, SBTS professor and author of the upcoming book Removing the Stain of Racism from the Southern Baptist Convention. “But some evangelicals who confuse the gospel of Jesus Christ with political power will chastise the black and brown evangelical because they don’t always share the same political views or American experiences.”

Isaac Adams, a pastor at Capital Hill Baptist Church, described several of the specific struggles black Christians face in white churches, including how “it feels like the majority doesn’t want to hear what it feels like to be black,” and “there’s no space for blacks to be righteously angry about issues that affect us, lest we arouse the ever-feared ‘angry black person’ stereotype.”

“All it takes is to be told once by a white brother or sister to just ‘get over’ the issues of race to feel like those in the majority are opposed to understanding you,” he wrote for 9 Marks.

A 2014 LifeWay survey found that African American pastors are less likely than white pastors to view racial reconciliation as a gospel mandate, but they are more likely to be actively involved in reconciliation efforts. Meanwhile, studies have shown that the wide gap in how black and white Christians think about race continues to widen.

Last year, SBC president Ronnie Floyd—who succeeded the denomination’s first African American president, Fred Luter—reported at the denomination’s annual meeting that 10,709 of its 51,441 churches have mostly non-white congregations. In 2014, 58 percent of its US church plants were also made up of mostly non-white members.

Black Southern Baptist leaders like Onwuchekwa find themselves balancing a sense of hope in their denomination with the tensions that remain.

A member of the ERLC’s leadership council, Onwuchekwa is optimistic about efforts made by SBC leaders, including Moore. Yet he sees the divide among Southern Baptists during the election, for example, as a reflection of how differently leaders within the same denomination are approaching many big issues, including race.

“I’ll be public in my affirmation. In the very same vein, I need to be public in my critique,” he said. “There are certain things where I can’t just embrace it all. There are certain things we’re going to take a stand on.”