As protests and vigils have become daily occurences in Ferguson, Missouri, so have online debates over how black and white Christians have (broadly speaking) reacted differently since teenager Michael Brown was killed by police officer Darren Wilson in a St. Louis suburb earlier this month.

With an increasing number of Christian writers arguing that a significant gap exists between black and white Christians, the latest findings from a significant ongoing study of religion and race in America offers some hard statistics—and suggest that polarization is increasing.

In the wake of the Trayvon Martin shooting, CT noted the growing gap in how black and white Christians now think about race. Researched by Michael Emerson of Rice University and David Sikkink of Notre Dame (and released by the Association of Religion Data Archives), the second wave of the Portraits of American Life Study found that divergent perceptions on race among black and white Christians have continued to widen since 2006.

CT directly reviewed five key findings:

1) More evangelicals and Catholics have come to believe that "one of the most effective ways to improve race relations is to stop talking about race." In 2012, 64 percent of evangelicals and 59 percent of Catholics agreed with this statement, up from 48 percent and 44 percent respectively in 2006.

The increases—driven by whites in both groups—were the only statistically significant changes among religious groups studied (apart from "other" Protestants: 56 percent agreed in 2012 vs. 41 percent in 2006). By comparison, 44 percent of black Protestants agreed in 2012 (vs. 37 percent in 2006), as did 52 percent of mainline Protestants (vs. 46 percent in 2006).

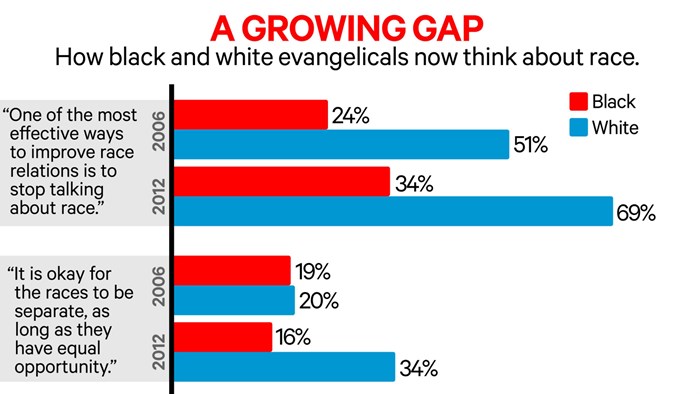

Among black evangelicals, 34 percent agreed in 2012, vs. 24 percent in 2006. Both findings were less than half the rate of white evangelicals (69 percent in 2012 vs. 51 percent in 2006).

2) More evangelicals now agree that "it is okay for the races to be separate, as long as they have equal opportunity." In 2012, 30 percent of all evangelicals agreed, up from 19 percent who said the same in 2006.

This increase was the only statistically significant change among religious groups studied, and occurred among white evangelicals (20 percent in 2006 vs. 34 percent in 2012), not black evangelicals (19 percent in 2006 vs. 16 percent in 2012).

By comparison, 30 percent of black Protestants agreed with the "separate but equal" idea in 2012, as did 24 percent of mainline Protestants, 20 percent of Catholics, and 24 percent of "other" Protestants.

3) On the question of whether the government "should do more to help minorities increase their standard of living," whites are no longer divided along religious lines the way they were six years earlier.

In 2006, more than 4 in 10 white non-evangelical Protestants agreed that the government should do more, versus only 3 in 10 white evangelicals and white Catholics. But in 2012, researchers found that "the religion effect disappeared" thanks to "substantial declining support" among white mainline Protestants (dropping from 42 percent to 21 percent) and white "other" Protestants (42 percent to 20 percent). Thus, "regardless of religious affiliation, whites were statistically identical to each other" by 2012.

In contrast, black Protestants saw a statistically significant increase in agreement that the government should do more: 68 percent agreed in 2006, while 84 percent agreed in 2012. (By comparison, 73 percent of black evangelicals said the same in 2006, declining to 69 percent in 2012.)

4) In 2012, 41 percent of black evangelicals said they think about their race daily, an increase from 36 percent in 2006. Meanwhile, 13 percent of white evangelicals said the same in 2012 (vs. 11 percent in 2006). By comparison, 48 percent of all blacks and 10 percent of all whites said the same in 2012 (vs. 42 percent and 10 percent, respectively, in 2006).

However, the only statistically significant change from 2006 to 2012 was a decrease among Hispanics: 54 percent said they thought about their race daily in 2006, but only 42 percent said the same in 2012.

5) More Americans now say they have been "treated unfairly" because of their race. And moreover, the increase from 2006 to 2012 was statistically significant for all groups: blacks (36% to 46%); Hispanics (17% to 36%); Asians (16% to 31%); whites (8% to 14%); as well as all Americans (13% to 21%).

Among religious groups, the only statistically significant change occurred among Catholics: 23 percent said they had experienced racial prejudice in 2012, up from 12 percent in 2006. By comparison, 43 percent of black evangelicals said the same in 2012 (up from 30 percent in 2006), as did 16 percent of white evangelicals (up from 11 percent in 2006).

Among evangelicals addressing these gaps were Matt Chandler, who pastors The Village Church in Texas and is president of the Acts 29 Network. On Monday, Chandler tweeted: "My son Reid has blonde hair and blue eyes & will more than likely never be seen as 'suspicious' by police #WhitePrivilege #Ferguson.”

Chandler expanded his argument on his blog later, saying that his comments had come after a friend had asked “What does white privilege have to do with what happened to Mike Brown?”

“The facts are still being debated, and I am hopeful that justice will take place once those can be established, but the way white people tend to perceive the situation in Ferguson, Missouri and in situations like this is through distinctively white lenses,” wrote Chandler. “We believe that our experiences, histories and benefits of our hard work are universal experiences for everyone. This is simply not true. I’m not a sociologist, but I’ve read enough, lived in enough places and have enough friends that I’m beginning to understand what motivates the frustrations and anger that can exist deep in the hearts of young black men.”

Thabiti Anyabwile, an assistant pastor for church planting at Capitol Hill Baptist Church in Washington, D.C., and Gospel Coalition council member and contributor, suggested that the majority of evangelical responses had been a “general lament” and “the expressing of sentiment.”

“There’s not yet been anything that looks like a groundswell of evangelical call for action, for theology applied to injustice. It’s possible (even likely) that I’ve missed a call for action from my colleagues and peers in the evangelical world. But I don’t think I’ve missed our most influential leaders with the widest reach. They’ve been silent en masse,” wrote Anayabwile, calling on his fellow conservative Christians to action.

“We don’t want to be your statistics—whether wrongful death statistics or church membership statistics. We want a living, breathing, risk-taking brotherhoodin the gospel lived out where it matters. Until evangelicalism can muster that kind of courage and abandon its privileged, ‘objective,’ distant calls for calm and ‘gospel’-this or ‘gospel’-that, it proves itself entirely inadequate for a people who need to see Jesus through the tear gas smoke of injustice,” he continued.

Josh Waulk, a former policeman who is now the pastor of counseling and discipleship at Lakeview Baptist Church in Clearwater, Florida, drew on his current vocation and his previous time in law enforcement.

“My seminary education would not have served me well in hand-to-hand combat during my career, so far as all this is concerned. It’s hard to imagine slugging a guy with Calvin’s Commentary on Ephesians, or calling on a fleeing felon to stop, because of his total depravity,” wrote Waulk. “The two occasions I was shot at, and the one occasion I discharged my firearm in the line of duty could only be prepared for at the range, and on the streets. I only wish the general public knew just how profound tunnel vision and auditory exclusion are for the PO in a threatening scenario. If they understood, the more reasonable would be less apt to ask the question, ‘Why did he have to…?’”

Trevin Wax, the managing editor of The Gospel Project at LifeWay Christian Resources, described Ferguson as “ripping the bandages off the racial wounds we thought were healing but instead are full of infection.”

“It is exposing the ongoing, deeply rooted structures of society that continue to feed and reinforce our prejudices," he wrote. "It is exposing how, decades after desegregation, we have self-segregated into neighborhoods and suburbs. Economic stagnation, family breakdown, and a drug culture are three strands of a noose with strangling force, suppressing people on the margins as the rest of society moves forward, blithely unaware of the realities faced by their fellow citizens across town. ... Privilege is real, and so is oppression. We live in the same country, in different worlds.”

Austin Channing, a resident director and multicultural liaison for Calvin College,challenged Christians who desired to positively affect the country's racial polarization to do more than "attend an MLK service or a Ferguson vigil" or "add people of color to your social media lists." "Choose a new church home and sit under the teaching of a black preacher for two years. Choose a new neighborhood where your fate is intimately tied to the fate of people of color," she wrote. "Go back to school and take a history class from a black professor where your academic success lies in his/her hands."

CT's previous responses to Brown’s death and demonstrations in Ferguson include an interview with John Perkins (founder of the Christian Community Development Association), an essay on when black victims become trending hashtags, a reflection from African-American pastor Bryan Loritts on "feeling the pain despite the facts," and an argument from social pyschologist Christena Cleveland for white Christians to "stand in solidarity with [their] black brothers and sisters."

CT regularly reports on diversity, racism, segregation, and reconciliation, including whether Sanford pastors' success could work in other cities and if churches should be perceived as "the ideal context for racial and ethnic reconciliation," following the Trayvon Martin case.

In the aftermath of the George Zimmerman trial, Cleveland, writer Margot Starbuck, Bishop of the Episocopal Diocese of Central Florida, Gregory Brewer, and the lead pastor of the Sanford-based Reality Community Church, Victor Montalvo, weighed in on how Christians ought to respond to the verdict.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month