In this series

Christians fleeing the Middle East will not take first priority under an updated version of President Donald Trump’s executive order on travel and refugees, which he signed Monday morning after weeks of debate and holdups in federal court.

The new order does away with explicit language about prioritizing religious minorities, as well as loosens Trump’s initial limits on who’s allowed to enter the United States.

Current visa holders, refugees already granted asylum, and travelers from Iraq no longer face restrictions, and the indefinite ban on refugees from Syria was reduced to 120 days—same as the overall refugee population. The executive order goes into place next Thursday.

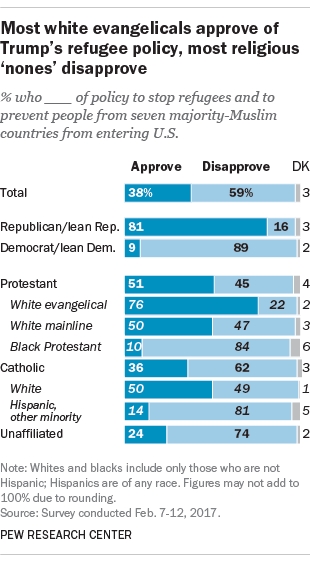

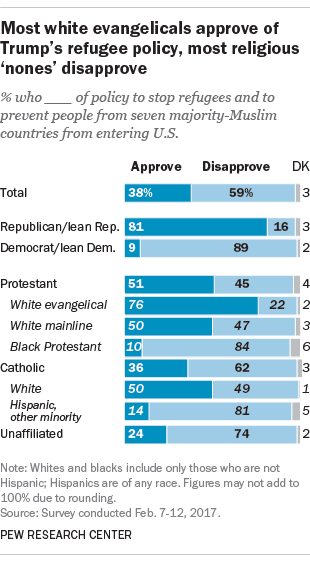

While surveys have found that most self-identified white evangelicals approve of Trump’s temporary moratorium on refugees, most evangelical leaders oppose it.

“The issuance of a new executive order on refugees and immigrants acknowledges that there were significant problems with the first executive order that caught up green card holders and others as they tried to enter the United States,” said Tim Breene, CEO of World Relief, the evangelical refugee resettlement agency forced to close five offices and lay off 140 employees in the wake of Trump’s decision to halve America’s intake of refugees from 110,000 to 50,000.

“However, this new executive order does not solve the root problems with the initial order—the cutting of refugee admissions by 55 percent and the inability for some of the world’s most vulnerable refugees to come to the United States. It is more of the same.”

Nearly half of leaders (46%) associated with the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) selected “immigration/refugees” as the top public policy issue that evangelicals need to address in 2017, according to the NAE’s recent monthly Evangelical Leaders Survey. (No. 1 was “religious freedom, selected by 63%.)

Self-identified white evangelicals, who lean Republican, showed the strongest support among faith groups for the travel ban, with a 76 percent approval rate in a Pew Research Center survey released last week. White evangelicals were also the only religious group whose endorsement of a temporary ban on Muslims entered the US grew over the past nine months, according to a recent PRRI survey.

“The US has a right to control who enters our country and to keep out those who seek to do us harm,” tweeted Jay Sekulow, chief counsel for the American Center for Law and Justice, which regularly advocates for persecuted Christians.

During an hour-long radio response Monday afternoon, Sekulow described Trump’s revised order as a more legally sound means of securing the aims of the President’s original directive. “As far as admitting minority religious refugees that are not protected, you can do that under the law and under this exemption,” he said. “It has a case-by-case review, which is exactly what we said is the way this goes forward.”

While white evangelicals overall are among the biggest backers of Trump’s efforts to restrict and better screen refugees, prominent evangelical leaders and institutions have consistently championed compassion toward refugees. Leaders at World Relief, one of nine agencies partnering with the government to resettle refugees, insist “compassion and security do not have to be mutually exclusive” and employ a biblical basis for their advocacy.

Recently, Atlanta pastor Andy Stanley sided with them. He preached on the church’s unique role in immigration and refugee policy last month and launched NotSoUnited.org to share his message that the church can “bridge the divide when compassion and national security collide.” (Here’s one attempt at a summary.)

“At the heartbeat of [Jesus’] ethic is that every single person was made in the image of God and demands and deserves respect—not because government requires it, but because God made it that way,” he said. “To ignore this is to undermine the liberty that makes this a nation people flee to rather than from.”

Trump’s new order considers “fear of persecution or torture” without explicitly calling out religious factors. The earlier one contained a provision to prioritize persecuted religious minorities once the refugee program resumed, and the president spoke in a TV interview about helping Christians in particular.

Nina Shea, director of the Hudson Institute’s Center for Religious Freedom, raised concerns that religious minorities in the Middle East need refuge more than ever.

“There’s a dire need for President Trump to issue a separate executive order—one specifically aimed to help ISIS genocide survivors in Iraq and Syria,” she wrote. “For three years, the Christians, Yizidis and others of the smallest religious minorities have been targeted by ISIS with beheadings, crucifixions, rape, torture and sexual enslavement …. The Christian community is now so shattered and vulnerable, without President Trump’s prompt leadership, the entire Iraqi Christian presence could soon be wiped out.”

Meanwhile, Arab Christian leaders expressed concerns to CT about any policy that explicitly prioritized one faith over another or required a religious test.

During the first month of Trump’s presidency, about 6,000 refugees came to the US, with about the same proportion of Christians (43 percent) as Muslims (46 percent), Pew reported using State Department data.

Iraq is among the top countries of origin for refugees coming to America. Citing Iraq’s cooperation with the US, the White House said Iraq will no longer be singled out with other Muslim-majority nations as a country of concern. The Preemptive Love Coalition, a Christian aid group based in Mosul, continues to feed and care for those who cannot escape.

“How do we take care of our Christian sisters and brothers in Syria and Iraq? Have we stopped to ask them what that would look like?” wrote executive director Jeremy Courtney following Trump’s first order. “I don’t mean just being a safe haven to run to when their churches and homes are destroyed by violence, but whether we as a nation are pursuing the policies and diplomacy that give them the greatest chance of surviving and flourishing where they are—so they don’t have to flee their homeland.”