In this series

It’s been a tumultuous year for refugee resettlement, and the latest ruling on President Donald Trump’s highly contested travel ban introduces more questions about the prospects for foreigners seeking asylum in the United States.

After months of holdups in lower courts and declining refugee admittances, today the US Supreme Court partially reinstated Trump’s executive order that bars refugees and travelers from certain Muslim-majority nations from entering the country. The high court will rule on the case this fall.

Monday’s court decision included some notable exceptions to Trump’s initial ban, including allowing refugees with “bona fide relationships with a person or entity in the United States” to enter the country and allowing such connected refugees into America even after totals reach Trump’s limit of 50,000 this fiscal year.

World Relief, an arm of the National Association of Evangelicals that serves as one of nine refugee resettlement agencies in the US, is waiting to hear more about the new qualifications. How the State Department interprets the decision will determine whether it will halt the flow of refugees or, possibly, allow in even more than planned.

Matthew Soerens, US director of church mobilization, said World Relief expects to receive guidance later this week, since the decision goes into effect Thursday.

Between 50 percent and 75 percent of refugees resettled through World Relief have some sort of tie to family or other contacts living in the US; however, some of these relationships may not meet the government standard for “bona fide relationships.” For example, “close familial relationships”—a term used in the decision—could apply only to immediate family or also to distant relatives in close contact.

Also, while the Supreme Court guidance specifically mentions employers and universities as examples of relationships with entities that would qualify refugees for entry, it’s possible that existing connections to sponsor agencies, Christian organizations, and churches could also apply.

Already, well over 48,000 refugees have entered the US this fiscal year, leaving only about 1,200 spots before reaching the Trump administration’s refugee ceiling of 50,000. (For comparison, the US resettled about 85,000 refugees last year; more than a third came from countries targeted by the travel ban, mostly from Syria and Somalia.)

If applied broadly, the “bona fide relationship” exception could put the country on track to welcome more refugees, putting the country closer to the 75,000-refugee ceiling Congress initially aimed for, Soerens said.

But that’s still up in the air. Compared to 2016—a record year for World Relief—the on-again, off-again travel ban has made refugee resettlement a moving target. The organization closed five offices and laid off staff when the executive order initial went into place.

“World Relief is still evaluating the impact of this decision on the refugees and immigrants we serve,” stated Scott Arbeiter and Tim Breene, World Relief’s president and CEO, after Monday’s Supreme Court decision. “We will continue to carry out legal analysis to determine how and whether the refugee resettlement program will proceed, and continue to believe that the program should allow the most vulnerable refugees to be resettled in the United States—including, but not limited to, those with family relationships.”

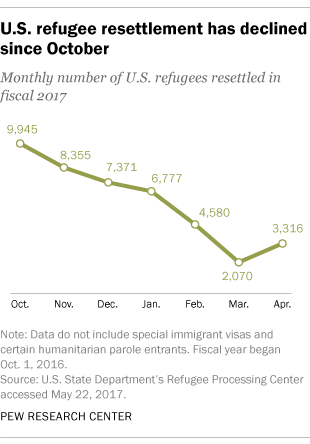

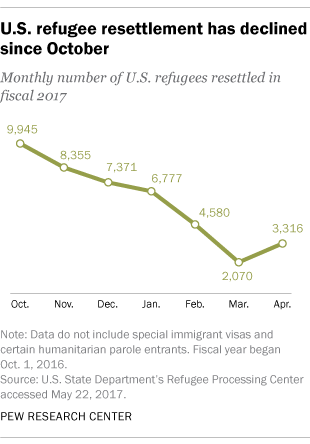

The number of refugees entering the US each month fell by two-thirds over the past year, down to about 3,300 a month in April, according to State Department figures analyzed by the Pew Research Center.

The drop from last October to March represents the longest consecutive monthly decline since records began in 2000. Once courts blocked the ban, some agencies tried to accelerate resettlement to make up for the low numbers.

Though the Trump administration’s ban focuses on Muslim-majority countries, it also reduces chances that Christian minorities trying to escape persecution in these countries can enter the US. Fewer refugees under Trump’s 50,000-person ceiling inevitably means fewer Christians.

While more than 500 evangelical leaders rallied to speak out against the travel ban and on behalf of refugees earlier this year, most white evangelicals support the move, citing concern for national security and immigration.

The original ban was revised in March to remove Iraq from the list of countries in question and to lift restrictions on green card holders. The revision also removed the prioritization of persecuted Christians, which CT reported was a matter of debate among American experts and Arab church leaders.