There’s nothing explicitly Christian about Kristi Jacobson‘s important new documentary Solitary: Inside Red Onion State Prison—yet God still manages to make a few cameo appearances. For those who know how to spot them, they offer the only hope to be found in this otherwise bleak and unsettling film, which premiered for broadcast on HBO in February.

In this latest outing, Jacobson, best known for her provocative work on the 2012 domestic hunger exposé A Place at the Table, takes viewers on an unprecedented journey into one of America’s most notorious “supermax” prisons for an artfully realistic and surprisingly intimate glimpse at what it’s like to endure solitary confinement in a modern segregation complex. It’s a disquieting experience that may help Christians better appreciate those familiar words God first spoke over Adam in the in the primeval garden of life: “It is not good that man should be alone.”

Some readers may be surprised to learn that the practice of solitary confinement actually owes its origins to a distinctly Christian penology—a philosophy of punishment in which the aim wasn’t merely to harm in kind, but to save and rehabilitate the offender. In the early 1800s, when Quakers and Anglicans first explored the idea of building a penitentiary, they imagined that separation and enforced silence would stimulate contemplative self-reflection, leading to sincere remorse and genuine repentance.

What they learned, however, is that prolonged seclusion more frequently drove offenders mad. Laudable as their intentions were, these innovators failed to account for the soul-withering consequences of long-term isolation on creatures fashioned of a triune, fundamentally communal God. It seems that offenders may occasionally benefit from brief seasons of contemplative solitude, but punishing them with long-term segregation is wholly counterproductive—unless, of course, the goal is to destroy rather than to reform.

After watching Solitary, it’s hard to imagine that much of the latter takes place at institutions like Red Onion. At this remote Virginia institution, most inmates spend 23 hours a day confined to cells about the size of a standard parking space—for months, years, even decades at a time. They eat, sleep, and relieve themselves in this tiny space, which they’re only permitted to leave a few times each week for showers and for very limited recreation. Whenever they move about the facility, they’re handcuffed and shackled, firmly escorted by a pair of officers in protective vests and closely supervised by an armed guard in an overhead control booth. Everything—literally everything—is rigidly controlled, with minimal opportunity for human contact and virtually no exposure to the outside world. As one inmate describes it, “In that cell by yourself, it’s like you’re not in prison. … You’re just away from life.”

Jacobson spent some time in one of these cells during filming. She commented about the experience in an interview with NPR:

When you’re in there looking out…you have such limited sight. I mean, nobody can hear you, and you can only see so much. And so in that world, in that cell, by yourself, you can essentially lose grasp on what’s real, what’s not.

In various ways, the inmates Jacobson profiles throughout the film evince this mind-warping response to radical solitude. The healthiest walk around in circles listening to their headphones, exercise for hours on end to wear themselves out, sing songs at the top of their lungs to keep the suicidal thoughts at bay, or engage in compulsive cleaning rituals in a feeble attempt to “fill and subdue” their tiny worlds. Some have been placed on psychiatric medications in the years since their admission to segregation, while others have already succumbed to serious psychiatric disorders.

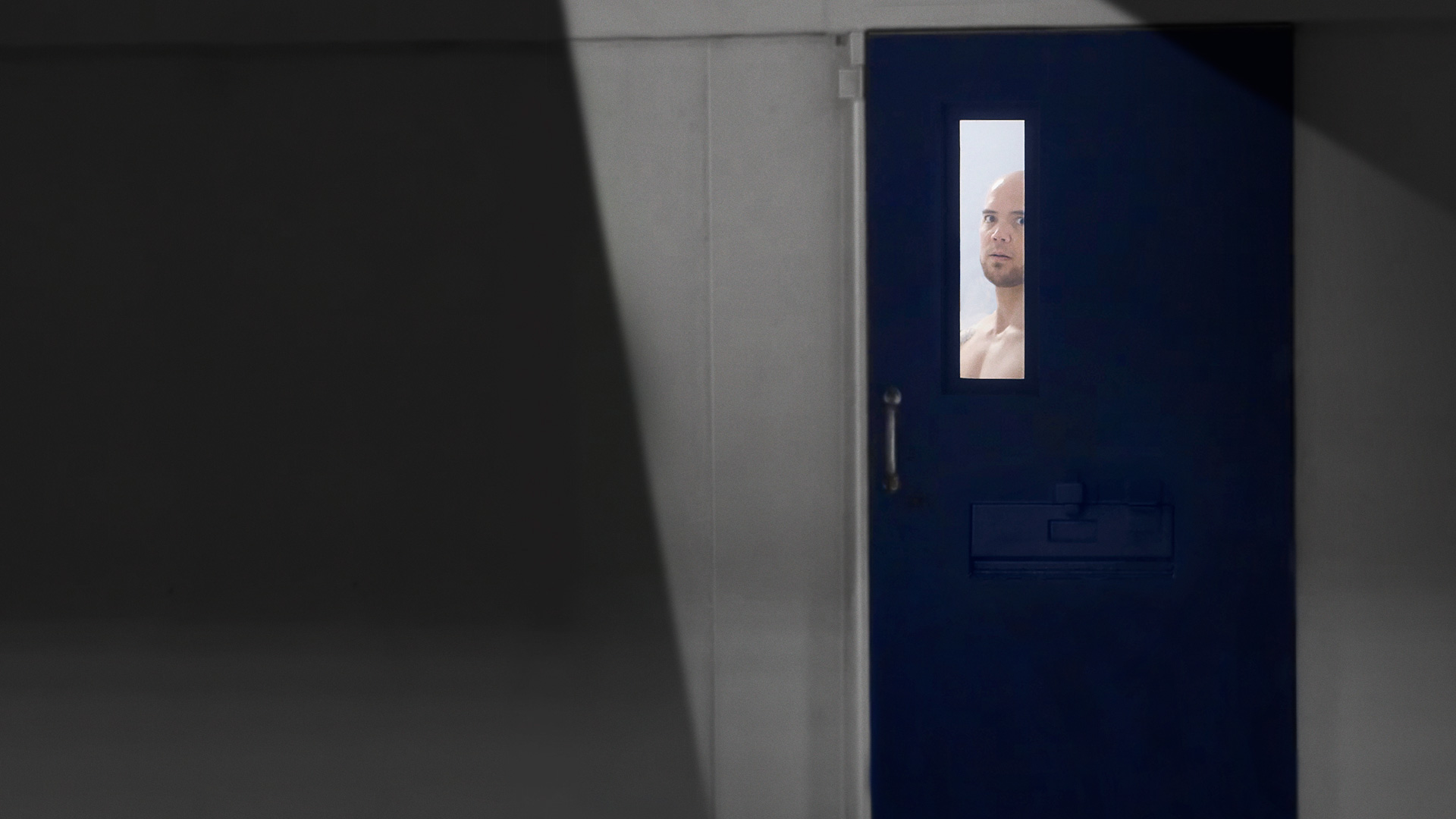

In an especially chilling scene, viewers watch as the unit’s mental health supervisor attempts to converse with a catatonic inmate in the infirmary. The man is awake, but utterly oblivious to the world around him. He simply stands in the observation cell, fixed in a posture of forlorn despair—a mere shell of a human being. I couldn’t help but wonder: How many more of the harried faces peering out from behind those myriad cell doors will end up here someday?

Given this abundance of misery, Solitary could have easily devolved into a monotonous exposition of pain. Yet as a testament to Jacobson’s finesse—and to the veteran skills of her crew—the film stands on its own, not merely as a compelling piece of advocacy, but as a hauntingly beautiful work of art. It accomplishes the latter primarily through its exquisite study in contrasts: clamorous noise punctuated by delicious silence, garish human edifice pictured against serene Appalachian countryside, creative cinematography lending visual interest to a clinically austere facility. Jacobson’s basic approach also wisely eschews the contrived sensationalism typical of the “true crime” genre. What viewers see and hear are the routine, brilliantly edited sights and sounds of Red Onion itself—no more, no less.

Still, for all its craftsmanship, Solitary offers precious little hope. It does a fine job of exposing viewers’ minds to the essentially dehumanizing nature of long-term segregation, but it stops short of casting a concrete vision for what an alternative reality might look like. That’s not necessarily a weakness, of course—it simply means that viewers must decide for themselves whether and how to respond to the suffering they witness here.

Fortunately, though, there are faint but important signs of life that this bastion of institutional death hasn’t yet managed to extinguish. One of the most touching occurs as two inmates, Vito and Lars, converse with each other via the air vents in their cells. It’s the only time when the camera captures an organic smile on an inmate’s face—something akin to genuine happiness in a sea of melancholy. “He knows me,” Vito explains. “Like, he can tell in my voice when something’s wrong…because he knows me that much.” To hear the way Vito gushes over this narrow social outlet, one might think he was Lars’ long-lost brother instead of a stranger he met in prison. But it’s not hard to understand why he feels this way. After all, isn’t that what all of us crave most—to know and to be known?

Another touching scene occurs as two inmates discuss such mundane topics as their breakfast and favorite TV shows while they spend an hour out of their cells chained to tables, rolling plasticware in paper napkins—the highest privilege these particular offenders can earn for good behavior. “Out here working,” one says, “we can talk to each other about things on the TV and stuff like that. And that’s good.” (Indeed, it is. Work and relationship are fundamental to the way God fashioned human beings to thrive.)

These and other “throwaway” moments are typical of the grace with which Jacobson treats Red Onion’s inhabitants. Without whitewashing the serious nature of their crimes or minimizing their potential for violence, she invites viewers to see them for the complex human beings they really are, despite their troubled personal histories. In a very real way, she asks viewers to see them the way God sees all of us. Apart from Christ, we’re no better than any of the miscreants behind those cell doors.

Perhaps it’s telling, then, that Jacobson bookends her film with the thoughtful reflections of Randall, the one inmate whose salvation doesn’t seem to be in question. Deemed too dangerous to ever return to the general population after using an improvised shank to cut the throat of an inmate who threatened to rape him, Randall represents at once both the volatile kind of offender for whom a place like Red Onion is necessary as well as the remorsefully self-aware sort of individual whose meaningful rehabilitation is likely to diminish the longer he is kept in segregation.

At some point during his eight years here, he apparently invited Christ to share the cell with him, because when we catch a glimpse of his personal property, we can’t help noticing an unabridged Matthew Henry commentary and an exhaustive Strong’s Concordance. Near the end of the film, we also catch him praying over a meal in his cell. Most importantly, though, he takes responsibility for his crime. “I killed a man,” he admits. “Am I being punished enough? In my opinion, no—not even close.”

Christians may be thankful that Randall no longer walks this doleful path alone—but they might also wonder what seasoning influence he might have on others like him in general population, what lost opportunities for positive influence will be squandered on the decades he spends withering in isolation.

There’s a brief section near the film’s midpoint when the camera lingers over a statue of Jesus in a cemetery. I’m not sure whether Jacobson intended anything especially profound by it, but at this moment, I found myself pondering something an inmate says during the film’s first few minutes:

I feel like I’ve been buried alive in the ground, and just—everybody’s just basically walking around over the top of you. You can hear them, but they can’t hear you. That’s the way I feel—forgotten.

As I gazed on this fleeting image of my Savior in a rural Virginia cemetery, I wondered: Is Jesus the only person who still hears the cries of the troubled souls languishing, voiceless and forgotten, behind Red Onion’s opaque concrete walls?

I hope not, because such apathy simply isn’t an option for Christians. “Remember the prisoners as if chained with them—those who are mistreated—since you yourselves are in the body also,” writes the author of Hebrews (13:3 NKJV). Our shared humanity with the 80,000 men and women presently enduring long-term solitary confinement in the United States ought to compel our interest in their suffering, even if it doesn’t necessarily command a particular response. Solitary doesn’t pretend to suggest what it might look like for Christians to “remember” these prisoners, but one thing is certain: After viewing this film, none of us can plead ignorance.

Johnathan Kana is a freelance writer, composer, and armchair theologian who met his Savior in a profound new way when he found himself rediscovering the Bible in the seminary of hard knocks. He is a regular contributor at Think Christian and journals on themes of restorative justice at his blog Redeem Your Time. He lives with his family in central Texas.