In this series

At the very beginning of the Reformation, the principal Bible available was the Latin Vulgate, the Bible Jerome had originally produced in Latin in A.D. 380—though by the time of the Reformation it has undergone significant textual corruptions. It included both a translation of the Hebrew Old Testament and the Greek New Testament, plus Tobit, Judith, Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach, Baruch, some additions to the Book of Daniel, and 1 and 2 Maccabees.

The Bible was not a book the general public was familiar with. It was not a book most individuals or families could own. There were pulpit Bibles usually chained to the pulpit; there were manuscripts of Bibles in monasteries; there were Bibles owned by kings and the socially elite. But the Bible was not a book possessed by many.

Furthermore, it was rare to find a Bible in the language of the people. There were a number of German translations in existence by the time of Luther, and one French version published already in 1473. But it was still the case that the Latin Bible was by far and away the principal Bible available. The well-educated social elite could read Latin, but your average resident of England or France or Germany or Italy or Spain knew only snippets of Latin from the Mass. And indeed, often enough they garbled the snippets they knew. If you want to get a good feel for the poverty of biblical literacy in the general public in this era, read Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, written between 1387 and 1400 in Middle English. Confusion and misunderstandings of the Bible abound in Chaucer’s stories.

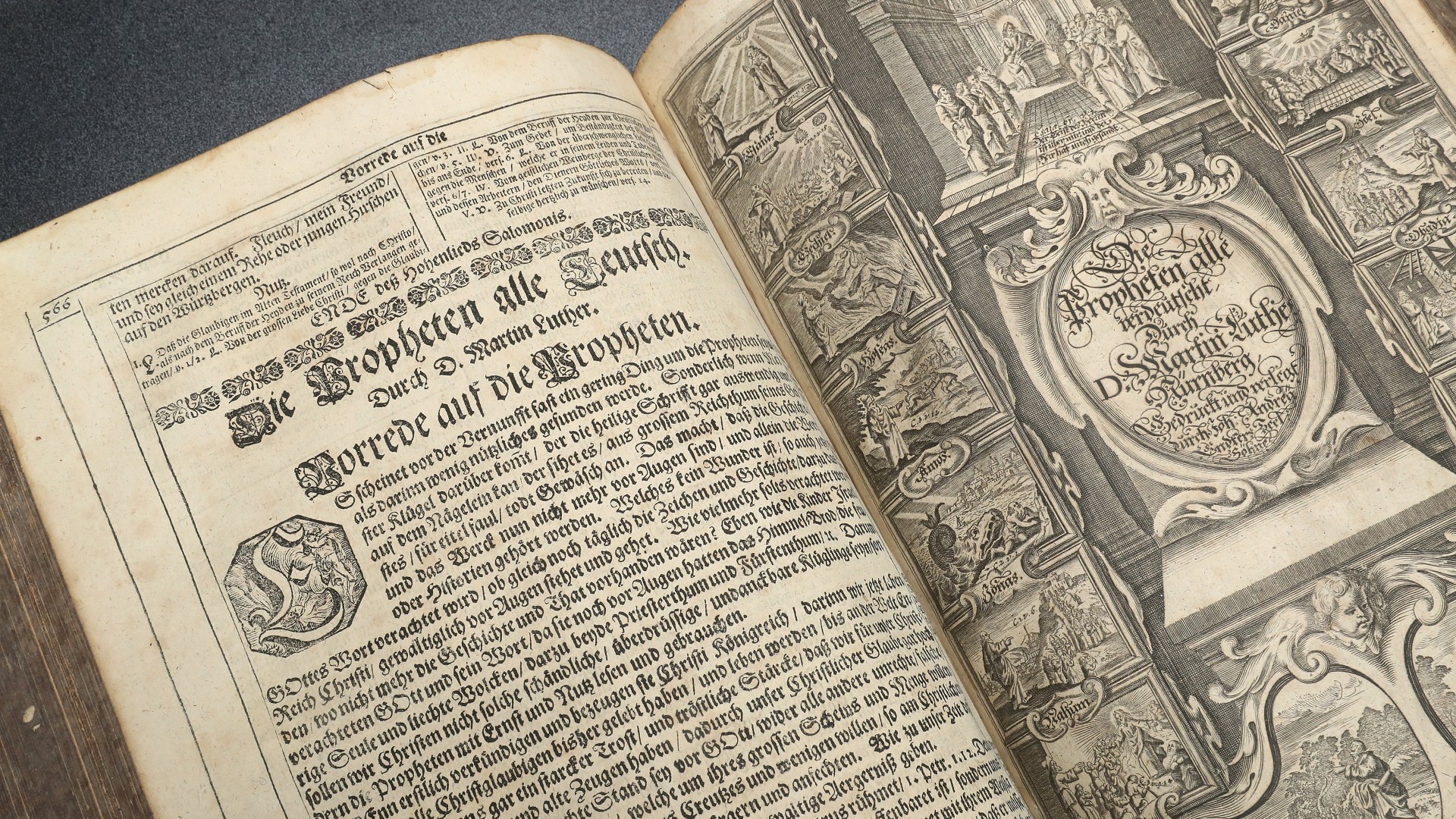

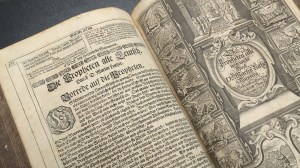

The Latin Vulgate was the Bible that Luther first studied, but he soon became aware of its deficiencies as he delved into the Greek text to discover his revolutionary insights. That led Luther to another realization: if things were really going to change, it would not come just by debating theology with other learned souls. The Bible needed to be made available in the vernacular (in this case German) and needed to be widely available. In my view, the most dangerous thing Luther ever did was not nail the 95 Theses to a door. It was translating the Bible into ordinary German and encouraging its widespread dissemination.

Luther’s ‘Heresy’

By 1522, Luther had translated the New Testament, and he had completed the full Bible by 1534, which included what came to be called the Apocrypha (those extra books from intertestamental Judaism). Luther kept revising this into his waning years, for he realized what a major change agent this translated Bible was.

Luther did not translate directly from the Latin Vulgate, and for some, this amounted to heresy. Luther had learned Greek the usual way, at Latin school at Magdeburg, so he could translate Greek works into Latin. There are tales, probably true, that Luther made forays into nearby towns and villages just to listen to people speak so that his translation, particularly of the New Testament, would be as close to ordinary contemporary usage as possible. This was not to be a Bible of and for the elite.

Philip Schaff, the great church historian, opined: “The richest fruit of Luther’s leisure in the Wartburg [castle], and the most important and useful work of his whole life, is the translation of the New Testament, by which he brought the teaching and example of Christ and the Apostles to the mind and hearts of the Germans in life-like reproduction. … He made the Bible the people’s book in church, school, and house.”

This act by Luther opened Pandora’s box when it came to translations of the Bible, and there was no getting the box closed thereafter. Needless to say, this worried church officials of all stripes because they no longer had strict control of God’s Word.

Forerunners and Followers

Too few people, however, have said enough about the precursors to Luther’s act of translating the Bible into the vernacular. For example, John Wycliffe’s team preceded Luther by a good 140 years with the translation of the Bible into Middle English between 1382 and 1395. Wycliffe himself was not solely responsible for the translation; others, such as Nicholas of Hereford, are known to have done some of the translating. The difference between the work of the Wycliffe team and Luther is that no textual criticism was involved; the Wycliffe team worked directly from the Latin Vulgate.

In addition, Wycliffe included not only what came to be called the Apocrypha, he threw in 2 Esdras and the second-century work Paul’s Letter to the Laodiceans as a bonus.

Like Luther’s efforts, Wycliffe’s work was not authorized by any ecclesiastical or royal authority, but it became enormously popular. And the fallout was severe. Henry IV and his archbishop Thomas Arundel worked hard to suppress the work, and the Oxford Convocation of 1408 voted that no new translation of the Bible should be made by anyone without official approval. Wycliffe, however, had struck a match, and there was no putting out the fire.

Perhaps the most poignant tale of this era is that of William Tyndale. Tyndale lived from 1494–1536 and was martyred for translating the Bible into English. Tyndale, like Luther, translated directly from the Hebrew and the Greek, except presumably for cross-referencing and checking. He actually only finished the New Testament, completing about half of his Old Testament translation before his death. His was the first mass-produced Bible in English.

Tyndale originally sought permission from Bishop Tunstall of London to produce this work but was told that it was forbidden, indeed heretical, and so Tyndale went to the Continent to get the job done. A partial edition was printed in 1525 (just three years after Luther) in Cologne, but spies betrayed Tyndale to the authorities and, ironically, he fled to Worms, the very city where Luther was brought before a diet and tried. From there, Tyndale’s complete edition of the New Testament was published in 1526.

As Alister McGrath was later to note, the King James Version (KJV), or Authorized Version, of the early 1600s (in several editions including the 1611 one) was not an original translation of the Bible into English but instead a rather wholescale taking over of Tyndale’s translation with some help from the Geneva Bible and other translations. Many of the memorable turns of phrase in the King James—“by the skin of his teeth,” “am I my brother’s keeper?” “the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak,” “a law unto themselves,” and so forth—are phrases Tyndale coined. He had a remarkable gift for turning biblical phrases into memorable English.

But even the Authorized Version was not the first authorized English translation of the Bible. That distinction goes to the “Great Bible” of 1539, authorized by Henry VIII. Henry wanted this Bible read in all the Anglican churches, and Miles Coverdale produced the translation. Coverdale simply cribbed from Tyndale’s version with a few objectionable features removed, and he completed Tyndale’s translation of the Old Testament plus the Apocrypha. Note, however, that Coverdale used the Vulgate and Luther’s translation in making this translation, not the original Hebrew or Greek.

For this and various reasons, many of the budding Protestant movements on the Continent and in Great Britain were not happy with the Great Bible. The Geneva Bible had more vivid and vigorous language and became quickly more popular than the Great Bible. It was the Bible of choice for William Shakespeare, Oliver Cromwell, John Bunyan, John Donne, and the pilgrims when they came to New England. It, not the KJV, was the Bible that accompanied them on the Mayflower.

The Geneva Bible was popular not only because it was mass produced for the general public but also because it had annotations, study guides, cross-references with relevant verses elsewhere in the Bible, and introductions to each book summarizing content, maps, tables, illustrations, and even indices. In short, it was the first study Bible in English, and again note, it preceded the KJV by a half-century. Not surprisingly for a Bible produced under the aegis of John Calvin’s Geneva, the notes were Calvinistic in substance and Dissenting (disagreeing with the Church of England) in character. That was one reason the kings of England produced “the Authorized Version.” They needed a Bible that didn’t question Dieu et mon droit (meaning “God and my right,” the monarch’s motto that suggested his sovereignty).

What About the Apocrypha?

Notably, the Geneva Bible was the first to produce an English Old Testament translation entirely from the Hebrew text. Like its predecessors, it included the Apocrypha. In fact, the King James Bible of 1611 also incorporated the Apocrypha, including the Story of Susanna, the History of the Destruction of Bel and the Dragon (both additions to Daniel), and the Prayer of Manasseh.

In short, none of the major Bible translations that emerged during the German, Swiss, or English reformations produced a Bible of simply 66 books. It is true that beyond the 66 books the other 7 (or more) were viewed as deuterocanonical, hence the term apocrypha, but nonetheless, they were still seen as having some authority.

So when and where does the Protestant Bible of 66 books show up? This practice was not standardized until 1825 when the British and Foreign Bible Society, in essence, threw down the gauntlet and said, “These 66 books and no others.” But this was not the Bible of Luther, Calvin, Knox, or even the Wesleys, who used the Authorized Version. Protestants had long treated the extra books as, at best, deuterocanonical. Some had even called them non-canonical, and there were some precedents for printing a Bible without these books. For example, there was a minority edition of the Great Bible from after 1549 that did not include the Apocrypha, and a 1575 edition of the Bishop’s Bible also excluded those books. The 1599 and 1640 printings of the Geneva Bible left them out as well. But in any event, these books had not been treated as canonical by many Protestants.

Luther’s Most Influential Act

Luther could not have imagined in 1517 that his most influential act during the German Reformation, the act which would touch most lives and effect the budding Protestant movement the most would not be his Galatians or Romans commentaries, his theological tracts like “The Bondage of the Will,” or even his insistence on justification by grace through faith alone. No, the biggest rock he threw into the ecclesiastical pond, which produced not only the most ripples but real waves, was his production of the Luther Bible. But he was not a lone pioneer. He and William Tyndale deserve equal billing as the real pioneers of producing translations of the Bible from the original languages into the language of ordinary people, so they might read it, study it, learn it, and be moved and shaped by it. The Bible of the people, by the people, and especially for the people did not really exist before Luther and Tyndale.

Today, to speak just of English, there are more than 900 translations or paraphrases of the New Testament in whole or in part into our language. Nine hundred! None of the original Reformers could have envisioned this nor for that matter could they have imagined many people having Bibles not just in the pulpits and pews but having their own Bibles in their own homes. The genie let out of the bottle at the beginning of the German Reformation turned out to be the Holy Spirit, who makes all things new. This includes ever-new translations of the Bible as we draw closer and closer to the original inspired text of the Old and New Testaments by finding more manuscripts, doing the hard work of text criticism, and producing translations based on our earliest and best witnesses to the Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek texts of the Bible.

When the Luther Bible was produced based on Erasmus’ work on the Greek New Testament, there were only a handful of Greek manuscripts Erasmus could consult, and they were not all that old. When the KJV was produced in 1611, there was the same problem both in regard to the Old Testament and the New Testament.

Today, we have over 5,000 manuscripts of the Greek New Testament, most of which have been unearthed in the last 150 years and some of which go back to the second and third centuries A.D. We have the discoveries at the Dead Sea and elsewhere providing us with manuscripts more than 1,000 years closer to the original Old Testament source texts than the Masoretic text (the traditional basis for the Old Testament text), and closer than we were in 1900. God in his providence is drawing us closer to himself by drawing us closer to the original inspired text in the modern era.

The cry sola Scriptura can echo today with a less hollow ring than in the past because we know today the decisions taken by church leaders in the fourth century to recognize the 27 books of the New Testament and the 39 books of the Old (plus a few), were the right decisions. The canon was closed when it was recognized that what we needed in our Bibles were the books written by the original eyewitnesses, or their co-workers and colleagues in the case of the New Testament, and those written within the context of the passing on of the sacred Jewish traditions of Law, Prophets, and Writings that went back to Moses, the Chroniclers, and the great Prophets of old.

While we owe our source texts to the ancient worthies who wrote things down between the time of Moses and John of Patmos, we owe our Bibles in the vernacular to our Protestant forebears—Luther, Tyndale, Calvin, and others. Perhaps now, as we celebrate the 500th anniversary of the German Reformation, it is time to say that without Protestantism we might not have Bibles in the hands of so many Christians, and in so many languages. The work of bringing the Bible to the people that Luther, Tyndale, and Wycliffe began is not over. There are still places where Bibles are illegal or where no translation in the local language is available. But thanks be to God, the work can continue because the cry semper reformanda still rings true today.

Ben Witherington III is professor of New Testament interpretation at Asbury Theological Seminary. He is author of many books, most recently, A Week in the Fall of Jerusalem (IVP Academic).