One of Martin Luther King Jr.’s most enduring statements regarding the church was his observation that “the most segregated hour of the week” was 11 a.m. on Sunday.

King’s commentary on how the modern church had failed to racially integrate in any meaningful way may be decades old; however, those who study religiosity in the United States continue to see the difficulty in bringing together Protestant traditions that have historically split along racial lines.

Anyone who has participated in both can immediately attest to the differences between a traditional evangelical worship service, such as at a Southern Baptist church, and a service at a historically black church, such as an African Methodist Episcopal (AME) congregation.

But, are those distinctions mostly stylistic? Do African American Protestants adopt a different theological perspective than their white counterparts? The data points to a simple reality: These two groups that seem so disparate on the surface actually have much more in common than either realize.

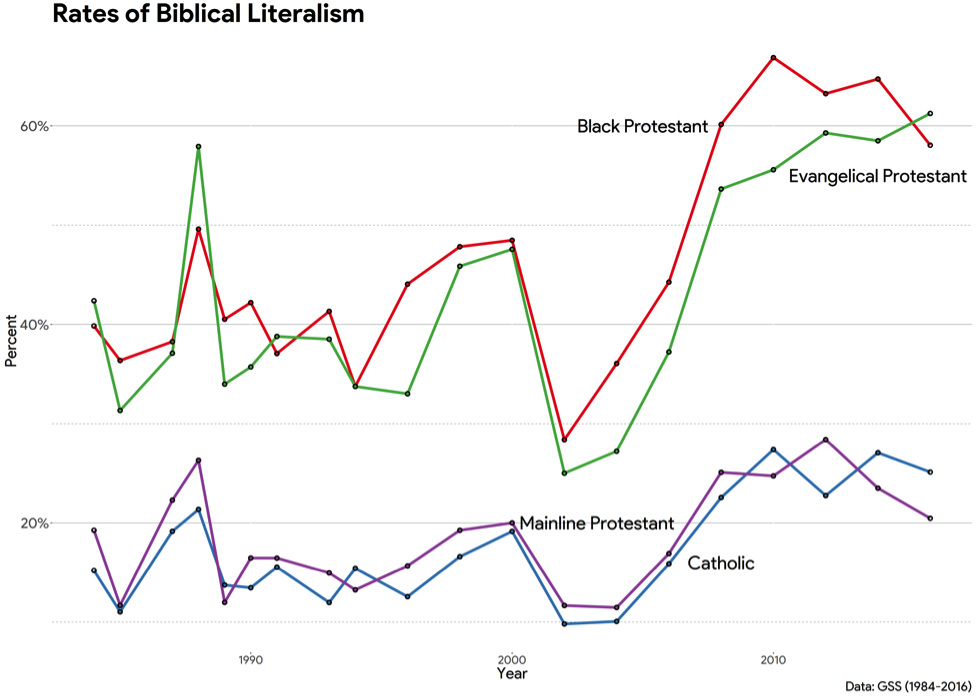

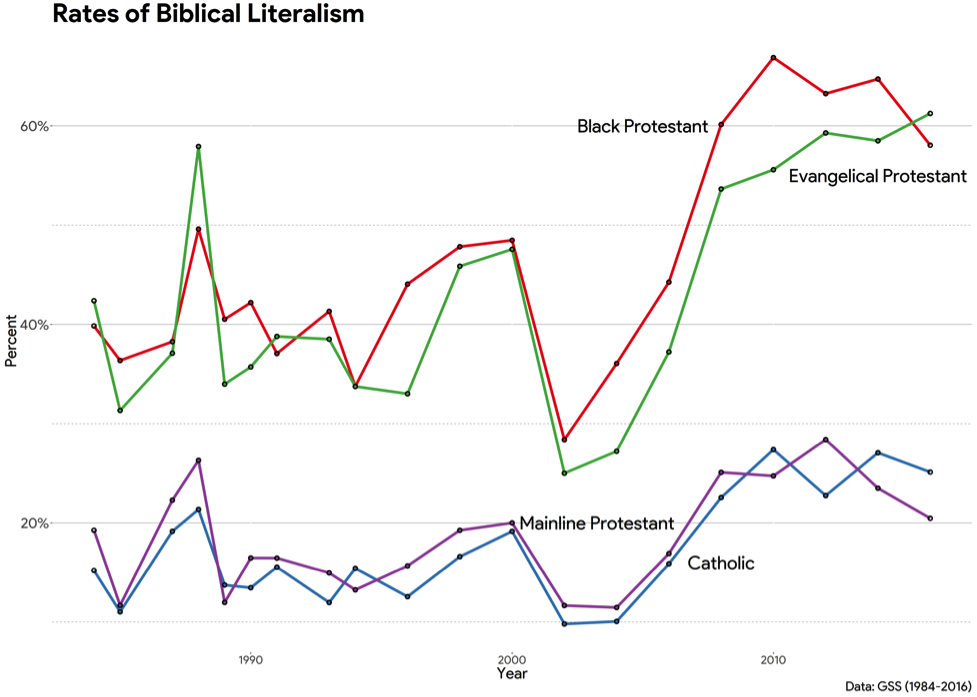

In 1984, the General Social Survey (GSS)—sociology’s gold standard due to its longevity and massive sample size—began asking respondents how they viewed the Bible, with responses ranging from “the Bible is the actual word of God and is to be taken literally” to “the Bible is an ancient book of fables, legends, history, and moral precepts recorded by men.”

The GSS findings reflect essentially two strains of theology in American Christianity. On the one hand, very few mainline Protestants and Catholics hold a literalist view of the Bible. Over the last 30 years, about 1 in 5 of each group would say the Bible is literally true.

On the other hand, significant majorities of both black Protestants and evangelical Protestants—90 percent of whom are white in the GSS survey—agree that the Bible should be taken literally.

In fact, for most of the span of the survey, black Protestants were actually more likely to believe in biblical literalism than their mostly white counterparts. As of 2016, approximately 3 in 5 black Protestants believe the Bible is literally true, which is not statistically distinct from the proportion for the survey’s evangelical Protestants overall.

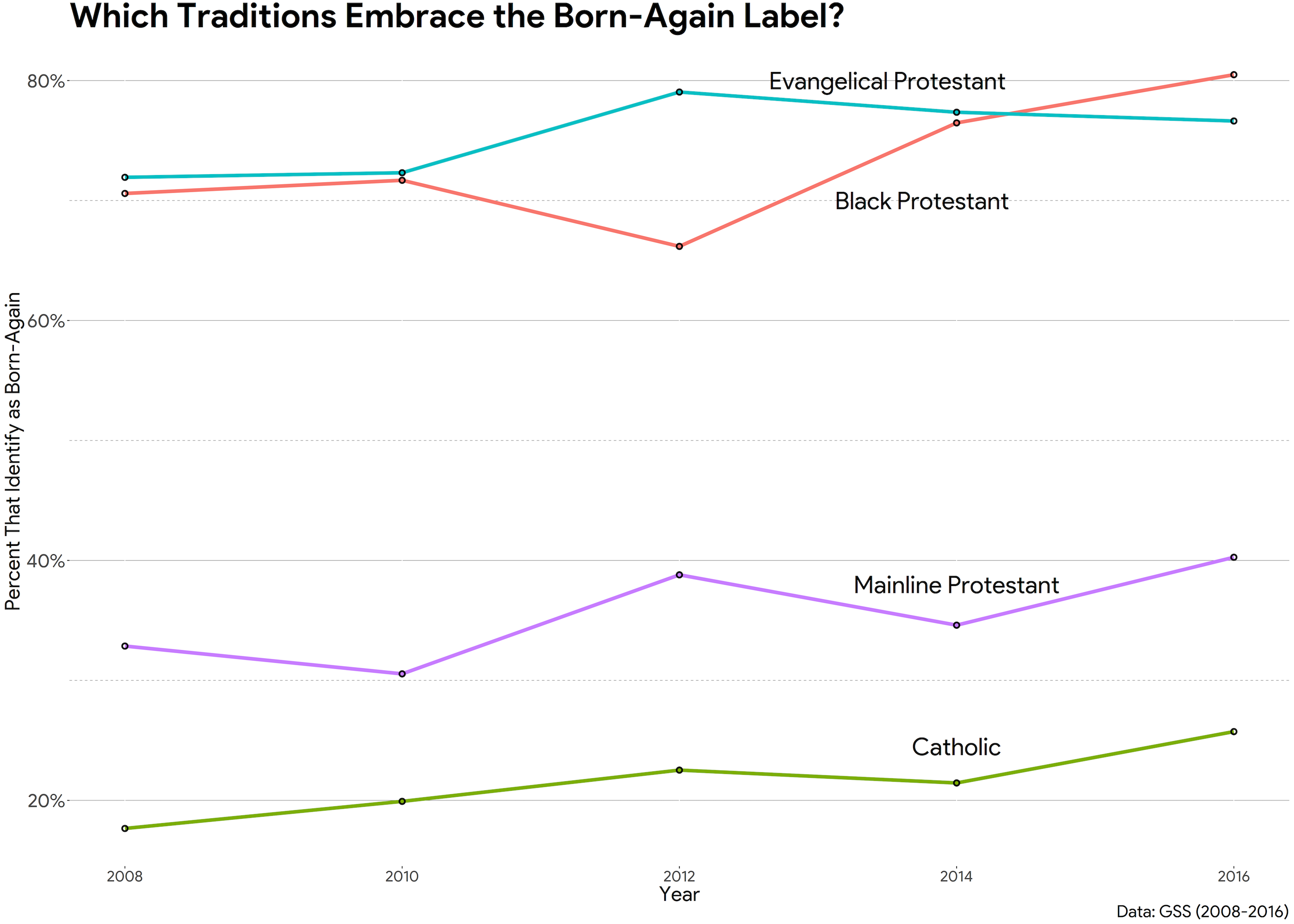

While Christians have recently renewed the debate over the term evangelical, the GSS queries Americans about another label often used in conjunction with it, born-again.

When asked about this term, the same pattern emerges. Catholics and mainline Protestants are much more hesitant to take on the label, while the GSS’s evangelical Protestants and black Protestants readily acknowledge that they have had “a turning point in their life when [they] committed [themselves] to Christ.” In the most recent wave of the GSS, conducted in 2016, over 80 percent of black Protestants affirmed their born-again status, slightly more than among its evangelical Protestants.

Together, this pair of questions gives the clear impression that black Protestants are just as willing to characterize themselves with major touchstones of evangelical Christianity: a high view of the Bible coupled with a born-again experience.

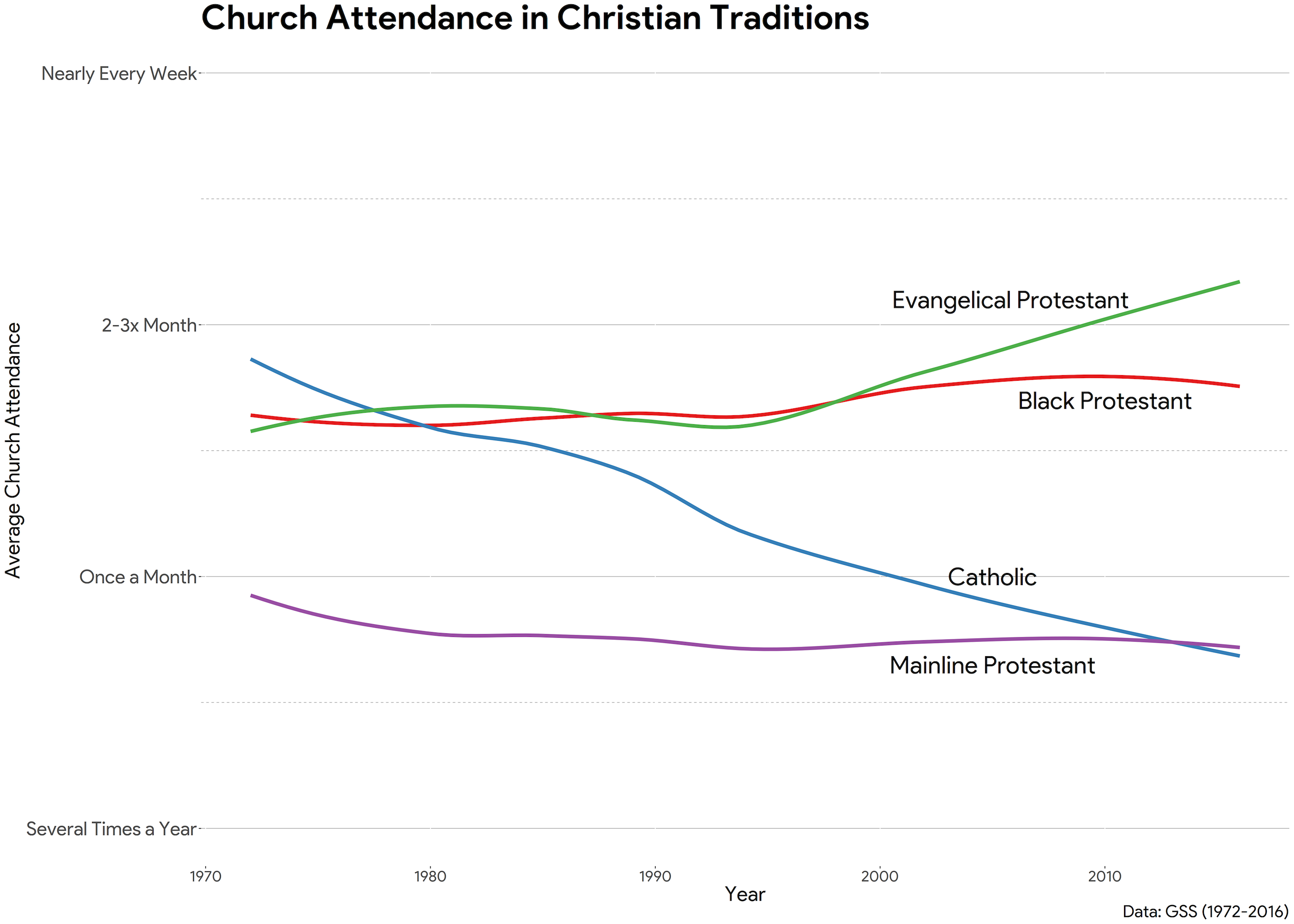

The similarities between evangelical Protestants and black Protestants in the GSS extend beyond religious beliefs to behavior. One example is the rate of church attendance, which is used as a barometer of religiosity.

The GSS has tracked the average attendance of these four major Christian groups in the United States going back to 1972.

Over the past four-plus decades, Catholics have experienced the sharpest decline in overall attendance. The average Catholic once attended Mass at higher rates than any other Christian group; now their attendance is at least as low as mainline Protestants.

Meanwhile, evangelical Protestants have seen relatively stable church attendance. Just in the last 10 years or so, their frequency has actually gone up slightly—a trend that separates them from their black Protestant counterparts.

Black Protestants, too, have experienced remarkably stable church attendance across the study period, averaging somewhere between once a month to three times a month. This result does not indicate that black Protestants attend church that much less than the GSS’s evangelical Protestant group; but they clearly outpace mainline Protestants and Catholics.

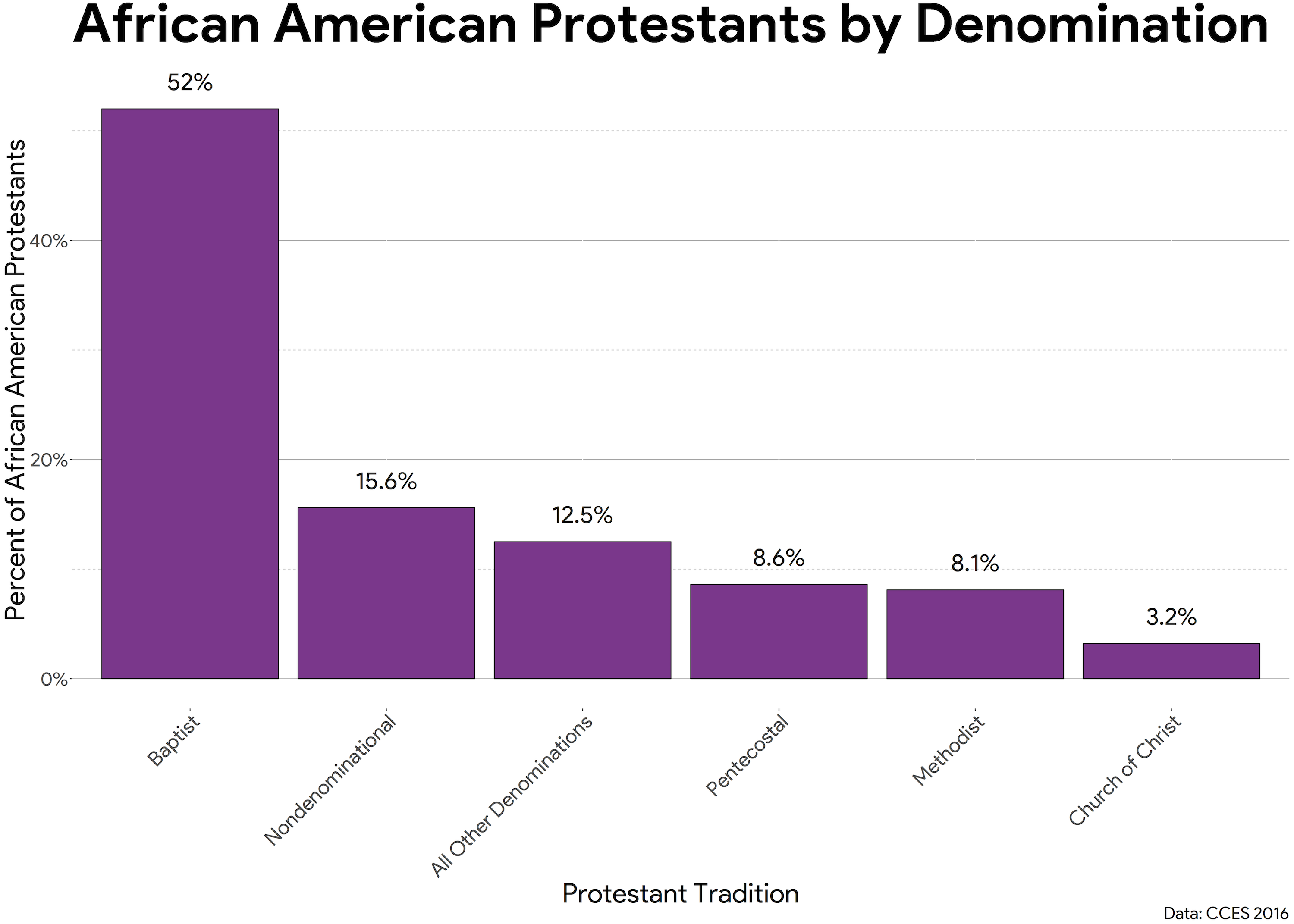

They also are largely attending churches in the same denominational families as most white evangelicals. More than half of black Protestants identify as Baptist, followed by nondenominational, according to data from the 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES).

These are the two most popular affiliations for American Protestants overall, and both nearly always fall under the evangelical banner. [Editor’s note: While Baptist is a broad term that covers an array of evangelical, mainline, and historically black groups, the Southern Baptist Convention—America’s largest Protestant denomination with about 15 million members—now counts 1 in 5 of its congregations as non-Anglo.]

An undeniable portrait of these somewhat unlikely faith allies emerges: When comparing the GSS’s black Protestants and evangelical Protestants on nearly any metric of traditional religiosity, there are not significant differences between the two groups. Theologically, black Protestants are just as conservative as evangelicals.

So, why do social scientists continue to place them in an entirely different religious category than their white counterparts? The answer is not religion; it’s politics (which, as CT previously reported, keeps evangelicals white).

In the 2016 GSS, respondents were asked to describe their party identification, ranging from strong Democrat to strong Republican.

It’s clear that black Protestants are overwhelmingly aligned with the Democratic Party. In fact, 42 percent described themselves with the most liberal option, “strong Democrat.” Only 10 percent of all African American Protestants affiliate with the Republican Party.

Evangelical Protestants are undoubtedly more disbursed across the partisan spectrum, but their politics lean decidedly to the right. Over half of evangelicals describe themselves as Republicans, and just a third (33.1%) align with the Democratic Party.

The split played out in the most recent presidential election: 88.6 percent of black Protestants voted for Hillary Clinton, while 78.7 percent of evangelical Protestants voted for Donald Trump. The gulf between these two groups, who otherwise resemble each other on matters of faith, is enormous from a political perspective.

King’s impact will be debated by scholars and theologians this week, the 50th anniversary of his assassination, and for years to come. At a time when the political divides within the American church remain as stark as they’ve been in decades, it may help Christians to remember the common ground they share with fellow believers. Such bridge-building strengthens the church and honors the legacy of the legendary leader who lamented our Sunday morning segregation.

Ryan P. Burge is an instructor of political science at Eastern Illinois University. His research appears on the site Religion in Public.