Scientists are finding it easier and easier to alter a baby’s genes, thanks to the groundbreaking CRISPR method. But Americans are divided on which uses of the new technology are appropriate or not.

And for the religious, the ethical lines are even more stringent, according to the Pew Research Center.

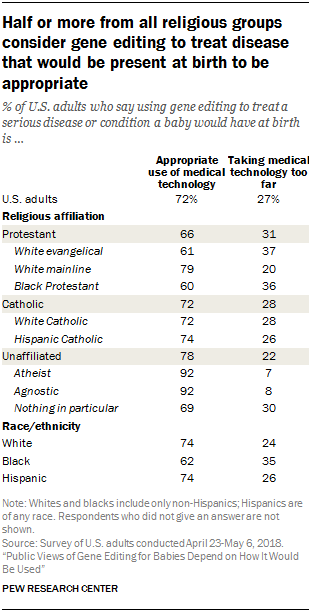

In a new report released this week, Pew found 72 percent of Americans support the use of gene editing to help cure a serious congenital disease (one present at birth), while only 57 percent of the highly religious agree. (Pew identifies highly religious Americans as those who attend services at least weekly, pray daily, and say that religion is very important in their lives.)

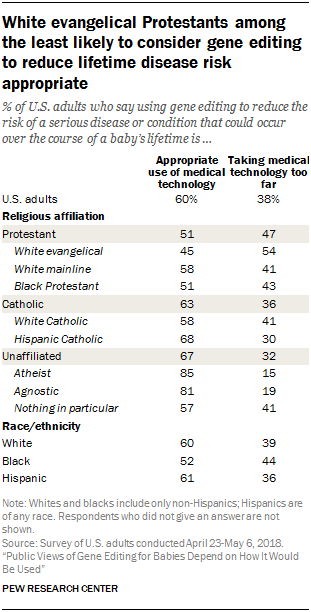

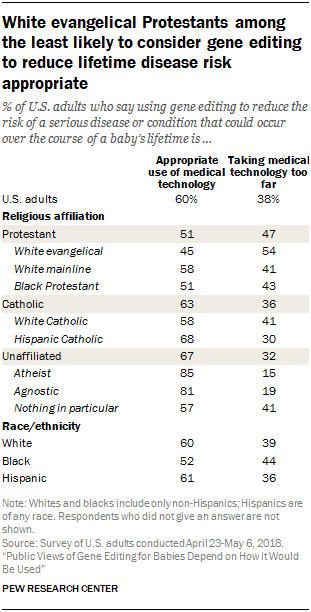

In the future, medical professionals may also be able to use gene editing to reduce the risk of a health condition that would crop up later in life. Only 60 percent of Americans felt that would be appropriate, while support among the highly religious dropped below 50 percent.

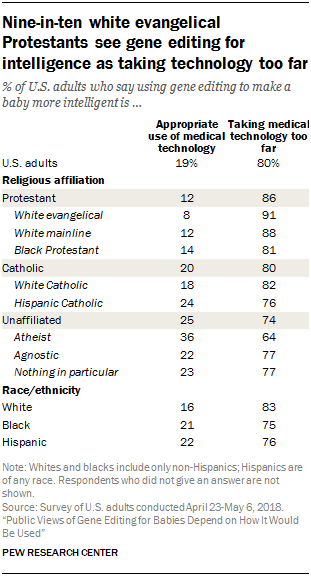

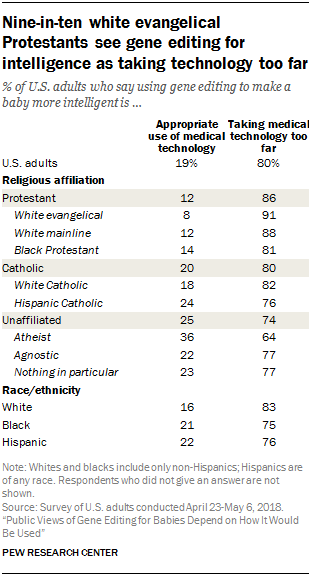

Among the three choices Pew listed in its survey, respondents felt the most inappropriate use of gene editing would be enhancing a baby’s intelligence: 80 percent of Americans believe that would be taking medical technology too far, as do 94 percent of the highly religious.

Overall, white evangelicals and black Protestants (two-thirds of whom identify as evangelicals according to Pew) feel the same about the applications of gene editing, though they invert on using it reduce disease later in life. [The breakdown for all religious groups is in the charts at bottom.]

Pew’s analysis of all the demographic variables found that self-identifying as evangelical on its own did not have any statistically significant impact on whether a person was more or less likely to approve of gene editing for any of the three scenarios: disease at birth, disease over lifetime, or intelligence. However, a high level of religious commitment did have an impact, with those Americans significantly less likely to approve of each of the three uses.

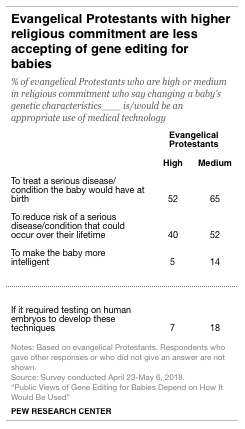

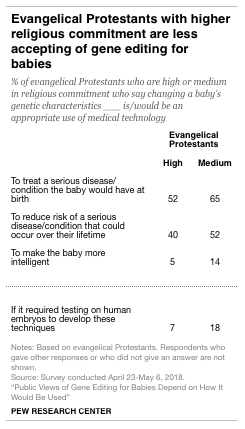

Among all evangelicals (not just whites), those that were highly committed were less likely to approve of gene editing for disease at birth (52%) than those that were only moderately committed (65%). The pattern was similar for gene editing for disease later in life (40% vs. 52%) and for making babies more intelligent (5% vs. 14%).

In a 2016 Pew survey reported by CT, 27 percent of white evangelicals with high levels of religious commitment said they would definitely or probably want gene editing for their baby in order to reduce disease. Meanwhile, 71 percent said such gene editing was “meddling with nature” and “crossing a line we should not cross.” (Among the moderately religious, the split was 41% to 56%.)

Before gene editing can be used for clinical use, it must undergo more development and trials. This will likely involve scientists testing the technology using human embryos—a subject that has been especially objectionable for evangelicals.

In the 2016 survey, white evangelicals (66%) and black Protestants (53%) said that gene editing would be less acceptable if it involved testing on human embryos. The 2018 Pew survey used different wording, but still found that most Americans (65%) believe testing on embryos would be taking technology too far. And this time, 88 percent of white evangelicals and 72 percent of black Protestants disapproved.

Support for gene editing also differed between men and women, with women generally less supportive of editing a baby’s genetic makeup. They especially frowned on the use of embryos in research (76%). And although women statistically have higher levels of religiosity, when researchers controlled for religion, women were still more likely to view gene editing as inappropriate.

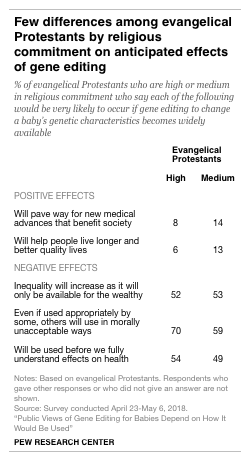

In a separate 2018 Pew survey, about half of Americans (52%) anticipate that in 50 years we will be able to eliminate all birth defects by genetically manipulating the genes of an embryo before it is born. In this week’s survey, most also see a dystopian future: 58 percent worry it will increase inequality; 54 percent are troubled by what other morally unacceptable forms this technology can take; and 46 percent expect unintended health effects.

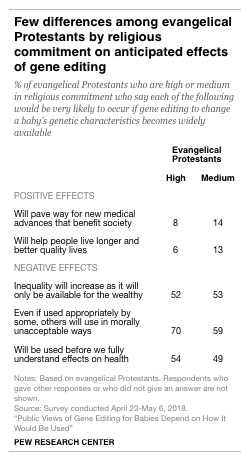

Among evangelicals with high levels of religious commitment, 52 percent believe gene editing will increase inequality and favor the wealthy; 54 percent believe the technology will be used before its full effects on health are understood; and 70 percent believe it will be used in morally unacceptable ways. Less-committed evangelicals are less worried.

Ironically, Americans who are more familiar with gene editing technology are more concerned about potential consequences: 64 percent are worried about inequality, and 65 percent are concerned that some will use the technology in morally unacceptable ways.

Yet the more informed also see more positive benefits of gene technology than others. In fact, Americans with higher levels of science knowledge, as measured by Pew’s nine-item index, are more likely to support gene editing: 86 percent approve of treating a baby with a congenital disease; 71 percent approve of lowering a risk of a genetic condition later in life; 24 percent approve of enhancing a baby’s intelligence; and 50 percent approve of testing embryos.

CT previously reported how most Christians want science to leave their bodies as God made them. Last year, pastor Nathan Barczi wrestled with the ethical implications of genome engineering.