The nurse hands my husband a bag for personal belongings and a bundle that includes a hospital gown, nonskid socks, and a heavy blanket. As Mike undresses, the weightiness of the moment is almost palpable. I do not allow myself to think of our four kids still sleeping right now at my parents’ house, an hour away from us here in the University of California, San Francisco hospital surgical wing. I push back at all the what-ifs that punctuate my thoughts like the beloved freckles that dapple my husband’s face. There is no doubt in my mind that we are meant to be here, but outcomes are never assured, and I tend toward worst-case scenario thinking.

A year ago, this journey had started off with a car ride conversation on the way to a neighbor’s wedding. “What would you think if I donated a kidney?” he asked casually.

My internal reaction: What if you die?! Who would you donate to, anyway? What if one of our four young kids or our relatives needs a transplant someday? What if I do? What if you get kidney disease or get in a car accident and injure the only kidney you have left? What are you thinking?!

My audible reply: “Why would you want to do that?”

It turned out Mike had read a magazine article and, not long after, happened upon a podcast on the possible domino effect of altruistic kidney donation. He thought it would be a nice thing to do. A youth group student of his had received a donation from his brother and it had gone well. Maybe there was someone out there who could benefit from his “extra” kidney as, medically speaking, a person only needs one.

I didn’t leave that conversation convinced, but his earnest sense of calling was enough for us to research next steps. The statistics were astounding: According to the National Kidney Foundation, every 14 minutes a new name is added to the kidney transplant waiting list in the United States—over 3,000 each month. At any given time more than 70,000 active patients are awaiting transplants, and on average every day 13 people die waiting for one.

Elective donation surgery has inherent costs and dangers. Over the course of months, my husband underwent extensive physical and psychological screening. Mike attended appointments with transplant program donor advocates where the improbable but real risk related to organ donation was explained at length. We signed legal documents and drafted end-of-life wishes in case of the worst. He talked to the human resources department at work and learned he would qualify for short-term disability with full pay during the recommended eight weeks he’d need to recover.

But when it came time to schedule a date for his altruistic donation—he did not have a specific recipient but was donating into “the system”—I got cold feet. I realized that I was supporting Mike in theory, all the while assuming at some point he would be denied. I had imagined, for example, that donors needed to be in peak physical condition. Surely my husband’s diet, conspicuously lacking in anything green, would have shut the door by now.

While I had been moved by the scale of the need, I had to confront the truth in my own heart: This felt too costly an act for a stranger.

Out of Our Abundance

Modern science and medicine, coupled with our bent toward rationalism, lead us to view our organs mostly through an anatomical-physiological lens. In the ancient world, though, kidneys were a revered part of the body endowed with mythological and metaphorical importance.

In Egypt, the kidneys and heart were the only organs left inside a mummy during the embalming process. The ancient Israelites understood the kidneys as being the seat of the human soul, a place of complex inner emotions tied to desire and discernment. The Talmud refers to them in much the same way that we would picture an angel on one shoulder and a devil on the other; one kidney was believed to be full of good advice and the other bad.

We might be surprised by how often the word for kidneys is used in the original text of the Old Testament. For example, in Psalm 139:13 when the psalmist credits God with creating his “inmost being” while still in his mother’s womb, the literal translation for “inmost being” is “kidneys.” It’s also translated as “soul,” “secret thoughts,” “innermost,” and even “heart,” since modern readers better understand the metaphorical gist of that organ. However, an Israelite would have connected the heart to the center of reason, and the kidneys would have mostly held what today we consider to be the symbolic role of the heart.

But when I turned to Scripture to deal with my husband’s desire to donate—and my own hesitations—there was much more to grapple with than just the significance of this particular organ. In the Gospel of Luke, John the Baptist exhorted a gathered crowd to “bear good fruits in keeping with repentance.” It was not enough for the people of Israel to claim the heritage of Abraham; the people needed to demonstrate that they belonged to God through their actions. When the people asked John how to do this, he responded, “Whoever has two tunics is to share with him who has none, and whoever has food is to do likewise.” By their generosity they would be known as God’s people.

While a kidney isn’t a direct equivalent to a tunic, nor would John the Baptist have had organ donation in mind, he called for the people to give out of their abundance. Jesus also exalted generosity in telling the rich young man to sell everything he had to give to those in need, to give out of abundance even to the point of sacrifice and discomfort.

God the Father has demonstrated this for us to its most radical end, giving his only Son for the life of the world. This gift that we celebrate anew every Christmas was of the ultimate value, given to us without hesitation, calculation of consequences, or regard for risk. “He gave his one and only son” (John 3:16, italics mine)—there was no other held in reserve, as there was in our case.

Given all this, could I really stand against my husband’s desire to give away something of such incalculable value?

A Need Right Now

Mike had made it clear early on that he would only move forward if I was 100 percent with him. When it came down to it, I had to admit I was split more like 60–40. I loved the idea of donation, but the reality was frightening. All of Mike’s test results would be considered current for one year, so we decided to wait and pray. I had not intended to be the roadblock to this good work, but this was too serious a matter to not be completely honest. I was afraid not only of the possibility of losing my husband, who had never been under anesthesia nor undergone surgery before, but I discovered I was possessive of that “extra” second kidney.

My husband gently pushed back: “What if you and everyone else in our lives never need one? What if someone dies who does need one now?”

Within weeks we were made aware of a distant acquaintance who was in need right now. Jeff was on the transplant list, but his health was deteriorating to the point that he might no longer be considered viable for transplant. A once-healthy middle-aged outdoorsman, he had collapsed on Thanksgiving three years prior, unaware of the advanced state of his kidney disease.

Nearly a dozen people had tested to be donors for Jeff but had either not been a match or been unable for various reasons to follow through. Mike approached me with a concrete story connected to a name I knew vaguely and asked if I would support him being tested to determine if he was a match. My acquiescence became my secret fleece. If that many people had already tested, the chances were slim of Mike being a match. If he was a match, I prayerfully committed to being all-in, despite my anxiety.

Jeff and Mike, it turned out, were a surprisingly good match for not being related. They were able to do a direct donation. Our families became dear friends in the months leading up to surgery, an unexpected gift that is not the norm for donors.

As my husband was wheeled off for surgery, I pulled back a curtain to hug Jeff before he was taken back to receive his new kidney. I was not assured a desirable outcome, but I did not doubt that this surgery was meant to be done. Incredibly, with a live donor donation, the moment the new kidney is spliced into the recipient’s system, it begins functioning.

While I had spent much energy fretting over the worst-case hypotheticals, ours was the best-case situation: a live kidney removed and directly placed into the recipient at the number one hospital for live kidney donation in the world. The surgery was a success and the reality of recovering from major surgery went as expected. Over a year later, both men are doing well. There have been no signs of rejection for Jeff.

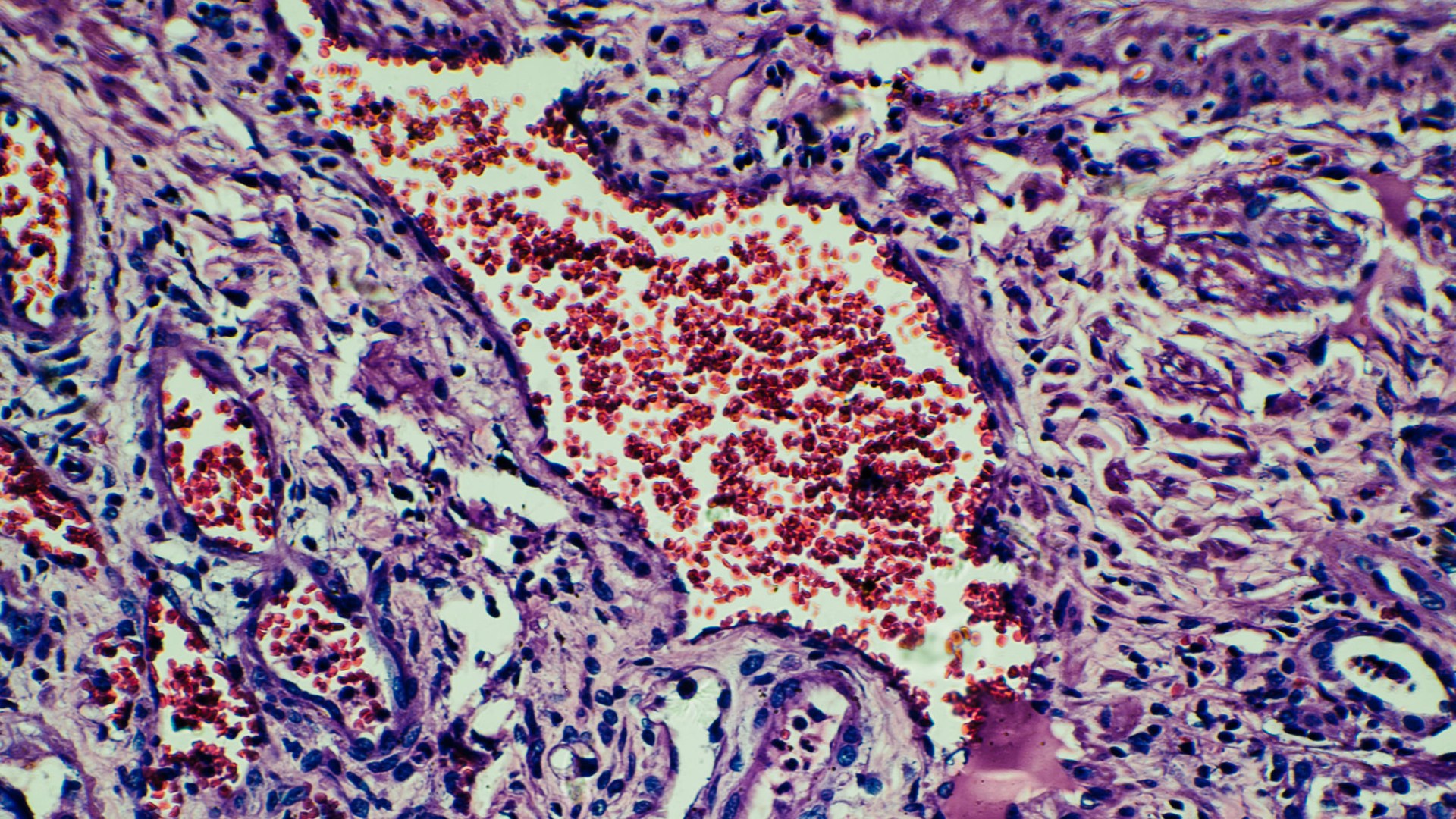

Mike’s last screening found that his remaining kidney has begun to grow. A little-realized grace of the human body is that the remaining kidney enlarges as it takes on the role of two, growing as much as 60 percent as it handles more blood and bulks up with extra proteins. In this mystery of God’s design, our bodies are fearfully and wonderfully made. I still believe there must be some reason he gave us two kidneys, and yet even after a radical act of generosity, God seems to have pre-ordained miraculous provision.

Here the physiological and the sacred meet. Originally, the kidneys were the only part of the sacrificial animal burned in a burnt offering unto the Lord. And Hosea reminds us of God’s attitude toward sacrifice: “For I desire mercy, not sacrifice, and acknowledgment of God rather than burnt offerings” (6:6). The words echo those I read in the Gospel of Luke that our radical generosity is a public acknowledgment that, body and soul, we belong to God.

Before the surgery, we hadn’t known that Mike’s remaining kidney would grow. Somehow it hadn’t come up in our initial research. It is, just maybe, a sign of the kidneys’ importance to God. It is certainly a sign of God’s graciousness in honoring the sacrifice—one radical act of generosity for another.

Aleah Marsden is a writer and MDiv student at Calvin Theological Seminary and serves as the director of communications for Living Bread Ministries.

Have something to say about this topic? Let us know here.