Once a man planted a garden. He watered it well and was delighted when shoots emerged. As weeks passed, those shoots grew into plants. Every day he watered and weeded, and his garden grew until one day he was ecstatic to see plants bearing fruit and vegetables. Now I can take a few days’ rest, he thought, content in knowing his efforts would produce a harvest. He left the produce to ripen on the plants.

A few days later, he went to his garden and was dismayed to see that what he had hoped to eat had already been eaten. On every plant was evidence of hungry rodents and rabbits who had raided his crop. So he decided to erect a fence.

A few days later, the man again went to his garden and saw the same thing. So he put up another fence, another, and another. Every time he checked, he found vermin had raided the garden. Finally he realized critters could go over, through, or under each fence. So he built a brick wall over a 10-foot-deep concrete foundation. He was sure nothing could get over or dig underneath. Then he confidently stayed away, giving the garden plenty of time to ripen undisturbed.

Weeks later, he climbed the garden wall and was horrified to find it was choked with weeds, the ground cracked, the plants wilted, and worst of all, his crop gone. The only thing left standing was his wall.

He looked closer and realized his garden was still full of critters—he had failed to clear them before building the wall. Furthermore, his wall had blocked out weeks of sunlight. Trusting in the wall’s protection, he had forgotten to tend the garden, failed to realize he was blocking the sun’s rays, and completely overlooked the greatest threat to his garden: the animals who had been inside all along.

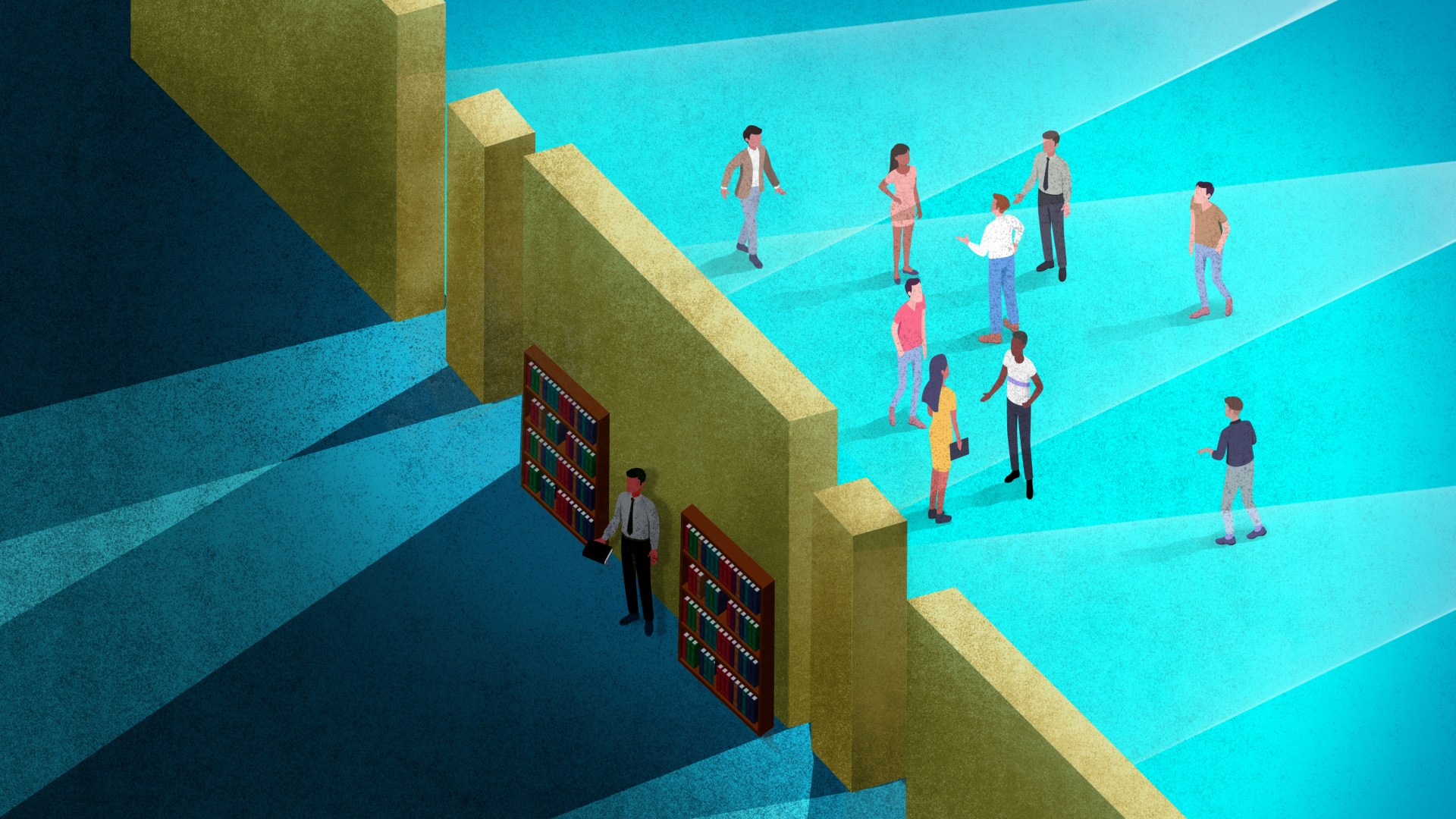

How many Christian leaders trust in similar walls—carefully built boundaries erected to protect us from threats to our moral well-being, to manage messy relationships, or simply to manage our time?

How many more will tragically discover that those walls not only will fail but that they can encourage internal decay?

These days, many churches are trying to recover from the pain and disillusionment of learning their leaders had well-honed and long-indulged appetites for power, pleasure, and profit. Many of these fallen leaders had strict rules and boundaries—often well-publicized—in place to preserve and protect their moral well-being. In 1989, after he is alleged to have begun abusing his position as pastor and engaging in inappropriate sexual encounters, Bill Hybels wrote a chapter called “How to Affair-Proof Your Marriage” in the book Christians in a Sex-Crazed Culture. In it, he advocated for adhering to boundaries for protection. And he wrote, “Recently, a pastor of a major church was exposed in having multiple adulterous relationships. When I asked him how this could have happened, he replied that he had created an environment where he had to answer to no one.”

In another article, he wrote an often-quoted story illustrating his own need for accountability, even in small things. When a staff member called him to task for parking in a “no parking” zone, he affirmed, “I’m not the exception to church rules, nor am I the exception to sexual rules or financial rules or any of God’s rules. As a leader, I am not an exception; I’m to be the example. …That’s why we all need people like my staff member to hold us accountable in even small matters. Because when we keep the minor matters in line, we don’t stumble over the larger ones.”

But for all Hybels’ talk about the value of boundaries, he found his way around both the standards he spoke of and the accountability he affirmed he needed. In investigating and responding to allegations of his misconduct, Willow Creek’s church board wrote, “Bill acknowledged that he placed himself in situations that would have been far wiser to avoid. We agree, and now recognize that we didn’t hold him accountable to specific boundaries.”

Hybels is hardly the only example of this. In 1999 James MacDonald wrote of the “moral fences” he had established in response to hearing of “the moral failures of the late ’80s.” Though he focused on sexual temptation in the article, the “boundaries of behavior” he put in place reveal a reliance on external safeguards that failed to protect him from alleged abuses of power and financial corruption.

So what happened? Why do these boundaries fail to protect some leaders and their congregations from sin? Every case, like every person’s story, is different. No single answer can explain the totality of the problem, particularly when sin is pathological. But among the many cautionary tales we can read in these stories, the inadequacy of boundaries may be the most counterintuitive. After all, some may look at such stories and implore us to strengthen our boundaries, to tighten the external controls we put in place to manage human behavior. But our well-meaning boundaries come with at least three major inherent flaws.

Laws Encourage Rebellion

I don’t hear many people talk about this first problem, even though it is baked into the gospel and obvious from the dawn of humanity. Paul wrote about it in Romans 7, in his discussion of the limited power of God’s law.

I would not have known what sin was had it not been for the law. For I would not have known what coveting really was if the law had not said, “You shall not covet.” But sin, seizing the opportunity afforded by the commandment, produced in me every kind of coveting. For apart from the law, sin was dead. … I found that the very commandment that was intended to bring life actually brought death. (Rom. 7:7–10)

In the following chapter, he goes on to explain that the law was powerless to save us “because it was weakened by the flesh” (Rom. 8:3).

The law, he says, not only reveals our sin but actually increases our desire to sin.

If you doubt this, open a package of M&Ms, put them out of reach on a high shelf, and tell a kid not to eat any of them. Then walk away but secretly watch while that kid gets creative. Better yet, place the candy in a locked box, tell the kid not to eat any of them, put the key in their pocket, and ask them to concentrate on something else. Guess what they’ll be thinking about all day?

As long as we are the guardians of our own boundaries—and ultimately we are—we can find ways around them.

For more biblical evidence, we need look no further than the Garden of Eden. With a world of pleasures and provisions surrounding them, Adam and Eve found themselves partaking of the one fruit they were forbidden to eat. How many times had they circled that tree, staring in fascination?

Here’s one important thing to remember about boundaries: We already have boundaries in God’s law. God’s law is good but cannot save us. If those boundaries are not enough to transform us and inspire obedience, because our sinful nature lives in rebellion against them, why do we believe our own rules will be enough to decrease our desire to sin?

Establishing our own boundaries, then relying on them to protect us from sin, comes from the same impulse that created the system of extra-biblical laws Jesus confronted so harshly: “They tie up heavy, cumbersome loads and put them on other people’s shoulders, but they themselves are not willing to lift a finger to move them” (Matt. 23:4). Rather than commend these religious leaders for their boundaries, Jesus confronted them with the truth about their condition before God: “You are like whitewashed tombs, which look beautiful on the outside but on the inside are full of the bones of the dead and everything unclean. In the same way, on the outside you appear to people as righteous but on the inside you are full of hypocrisy and wickedness” (Matt. 23:27–28).

Consider the example of former youth pastor Gary Welch, who was sentenced to 55 years in prison for sexual crimes. In discussing child sexual abuse in the church, he said, “It’s very important that churches and anybody has boundaries and guidelines. And our church did. I just chose to ignore them.”

For another example, witness Bill Gothard, whose many rules about dating relationships, sexual purity, and modesty may have fueled the desires behind his alleged abuse of young women. Or Ted Haggard, who “seemed to have a need to push boundaries.”

“The human heart is so inveterately proud and unsubmissive that it often uses religion and morality to express its rebellion,” wrote John Piper—who, though he took an eight-month leave from Bethlehem Baptist Church in 2010 for “a reality check from the Holy Spirit,” has not experienced a ministry meltdown like these other figures. “As Romans 10:3 says, ‘In seeking to establish their own righteousness, they would not submit to the righteousness of God.’ The pursuit of righteousness can lead to perdition.”

The fact is, rigid systems don't work. They may even lead us right into the sin we’re hoping to avoid.

Walls Isolate Us

Another serious problem is that walls and boundaries, by their very nature, place barriers between us and other people. This is not always a problem. In some cases, like abusive relationships, it can be healthy. However, our boundaries can also insulate us from important relationships where we might be known, vulnerable, and accountable (whether or not we want to be).

Boundaries can be excuses for isolation: We can use our own boundaries to tell ourselves it’s all right to avoid relationships that challenge us. They give us language to avoid messy encounters (words like “I need some time to myself” or “I need to protect my time” can be abused) and help us surround ourselves only with people who make us feel comfortable, smart, and important. They can help us manipulate the system when we have convinced ourselves we “deserve” to indulge our desires.

At the very least, our boundaries can keep us out of reach and out of touch with the people around us. In the time I’ve spent as an organizational leader, I have experienced the loneliness imposed by the invisible boundary between leaders and people they lead: being the last to know what everyone else is talking about, the one people are reluctant to “bother” with small problems, and the one who carries unknown burdens on their behalf. These are boundaries inherent in the organization’s structure; how much deeper isolation results when we take intentional steps to keep people away because we mistrust them or ourselves.

We do not exist above, separate from, or for the sake of God’s people. All church leaders are part of the body of Christ. “In Christ we, though many, form one body, and each member belongs to all the others” (Rom. 12:5). Part of our calling is to “warn those who are idle and disruptive, encourage the disheartened, help the weak, be patient with everyone” (1 Thess. 5:14). And we need others to do the same for us. We all need accountability, and for that we need to be in relationships with people who are ready and willing to call us to task.

But accountability partners are only as wise as we are honest. And all humans also need to be known simply for who we are. We need to carry each other’s burdens (Gal. 6:2) and confess our sins to one another (James 5:16). We need to leave the garden, to request and receive help, to be seen and loved in our weak moments, to interact with people who are different from us, to have awkward conversations, to listen and learn from others, to be genuinely human in situations where we can’t control the way people will respond. We need enough exposure to other people that we can’t avoid being exposed for who we really are.

If we use boundaries to keep us from these experiences, we will cut off the sunlight from our internal gardens.

The Problem Is in the Garden

This is true both metaphorically and biblically. The problem with each of us began in the Garden of Eden, and the problem is always going to live inside any fences or walls we erect around our lives, our bodies, or our hearts. James talked about it when he said, “Each person is tempted when they are dragged away by their own evil desire and enticed. Then, after desire has conceived, it gives birth to sin; and sin, when it is full-grown, gives birth to death” (James 1:14–15).

When we lean into boundaries, relying on them to keep us safe, we may be tempted to relax our vigilance over the true source of danger. And like rabbits in a garden, the sins of our hearts and minds will devour the fruit of ministry when we’re not looking.

We simply cannot rid ourselves of sin by cutting ourselves off from circumstances or relationships in which we can envision ourselves committing sin. Battling temptation and avoiding snares is wise and helpful. But we have to acknowledge that doing so does not diminish our capacity for sin. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, addicts who successfully live in recovery are the ones who avoid the substances that have held them captive and never forget their addiction. The same is true for those of us who have surrendered to Christ and still battle sin.

What’s a Leader to Do?

My early years were marked by neglect, fear, and other effects from a family of origin injured by what is now a well-publicized battle with severe mental illness. My adult years have included long efforts at healing, learning new stories about who I am, and unraveling coping strategies that long ago ceased to be helpful. Among these is an emotional dependence on food that has led to a lifelong battle with my body. As with many who face a similar struggle, my most natural weapon in this fight has been a commitment to live by dieting rules. And since study after study shows that diets don’t work, my strict boundaries have always been a setup for failure. True transformation is coming only through abandoning the self-imposed rules and restrictions and doing the work required not only to heal but also to find healthier ways to address my personal needs.

Leaders, the most fundamental thing we can do to preserve our integrity and ministries is to remember we are, first of all, people. We are just as human as everyone else. That means we were born into sin the same as everyone else, we are sometimes weak in the face of temptation, we spend a good portion of our lives in some kind of pain (if you haven’t yet, you will), and we have deep needs and some dysfunctional ways of meeting those needs. It means we all run a close second to the great accuser of humankind as our own second-worst enemies. It also means we need other people God has placed in our lives.

If we do not tend to the needs and inclinations of ourselves as people, leadership will become another tool to try to meet our personal needs. And that story never ends well.

It’s sometimes said that celebrities’ emotional development stops—or at least takes a dangerous detour—at the point when they become famous. Church leaders, on whom unrealistic expectations of holiness are often projected, can suffer a similar fate. Among the factors behind the failures of James MacDonald, Mark Driscoll, and others is a habit of aggressively marginalizing critics and surrounding themselves with people who reinforced their sense of celebrity and cleared obstacles from their paths.

In an interview that acknowledges some of his personal boundaries, pastor Max Lucado also spoke of the importance of spiritual vigilance. He talked about the temptation to internalize compliments: “Every time somebody says, ‘You’re such a wonderful spiritual leader,’ there is a temptation to believe that. Because I’m not. I may have a little more experience than they do, but I’m certainly not as good as they’re saying I am. But there’s a temptation to believe that I am.”

No matter who we are, we need people in our lives who will see us, know us, and be honest with us. We need to be in true relationships with people who are not impressed with us, who do not have a livelihood dependent on our success, and who are willing to remind us that we are no more important than anyone else and we cannot afford to be complacent about our capacity for sin.

There are no substitutes for inner work, humble transparency, open-handed leadership, and true relationship. Still, healthy boundaries can help us fulfill our God-honoring intentions for ourselves, our ministries, and our relationships with others. They can help us stick to the promises we have made and avoid temptations that can trip us up—particularly when we are vulnerable because of our own unmet needs.

The most successful approach to managing any chronic condition is often threefold. For example, for people with mental disorders, a combination of medication, therapy, and lifestyle changes is far more likely to achieve lasting results than one element alone. The same is true for the medication, education, and lifestyle adaptations that address conditions like diabetes, serious back pain, arthritis, asthma, heart disease, and others. Boundaries can work like medication—they are helpful, but they produce lasting change only in partnership with God’s protection and the kind of work that causes inner transformation and growth. Boundaries get us into trouble when we rely on them as a complete solution.

Self-satisfied dependency on rigid boundaries will isolate us from one another. It can lull us into a false belief that we can relax our spiritual fight. They tempt us to congratulate ourselves on our appearance of righteousness while weeds grow in untended gardens. By all means, we must draw boundaries where they will help us. But it’s dangerous to imagine they will reform us, protect us from moral decay, or eradicate the true source of sin. We can’t let down our guard. Sin begins in our own hearts and minds, and the most effective protections are the ministry of the Holy Spirit and equal, open relationships with brothers and sisters in Christ.

Amy Simpson is a leadership coach and an acquisitions editor for Moody Publishers living in the suburbs of Chicago. Her newest book is Blessed Are the Unsatisfied: Finding Spiritual Freedom in an Imperfect World (IVP, 2018).